Worlding Anew:

Rania Ghosn and Leen Katrib on Drawing Together Climate and Heritage

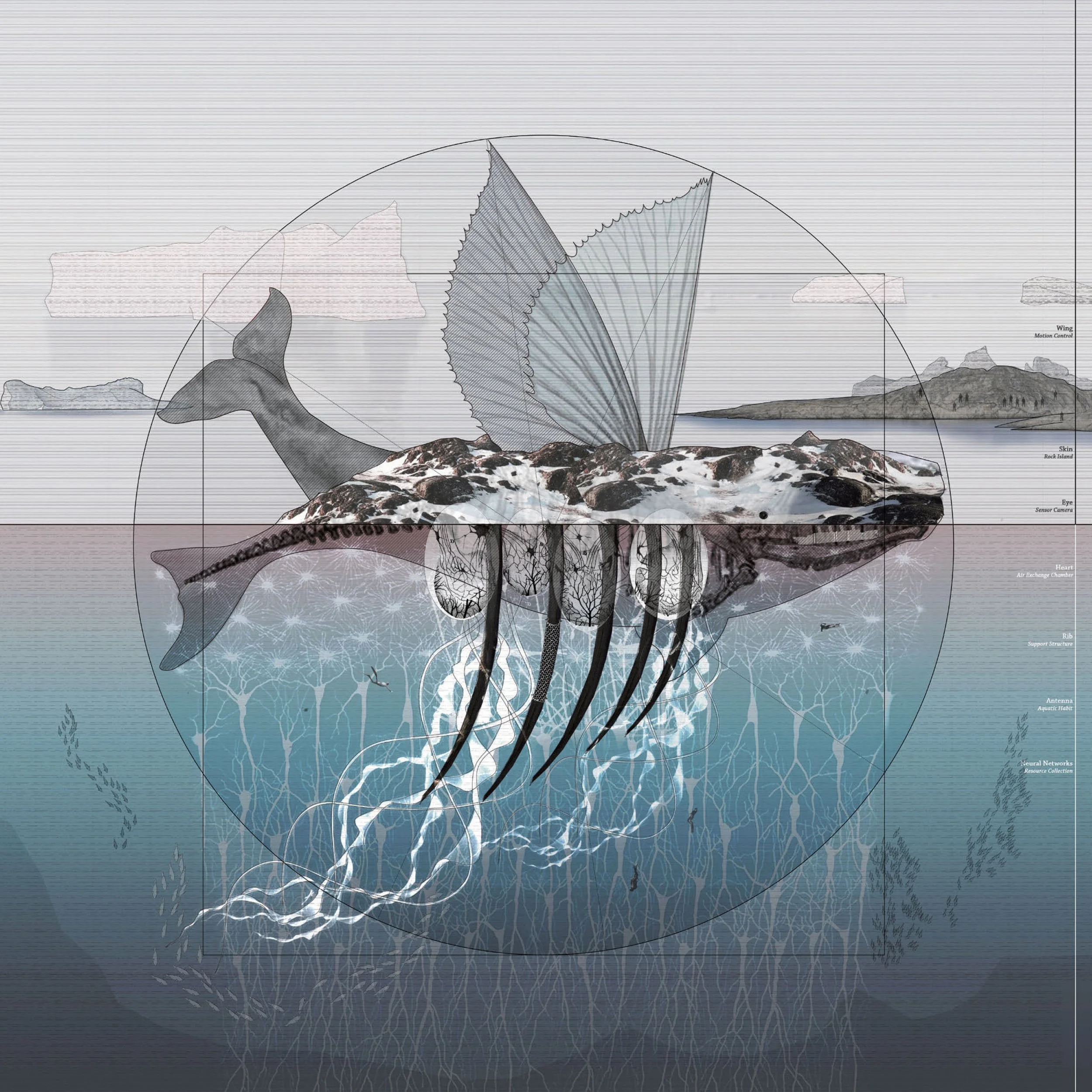

Illustration from “Galápagos Islands” in Climate Inheritance, 2023. Courtesy of the authors.

LEEN KATRIB:

Let’s start with the big picture then slowly zoom into the specifics. Where do you situate your new book, Climate Inheritance (2023), within the larger body of your work? Is it part of a continuum or a process?

RANIA GHOSN:

Climate Inheritance is the fourth book by DESIGN EARTH, which is a collaborative practice that I founded and have co-directed with my partner, El Hadi Jazairy, and a fabulous team of collaborators since 2011. Our work has addressed the climate crisis not only as a breakdown of physical earth systems, as critical as that is, but also as a challenge to the stories, images, drawings, and cultural systems of representation through which we relate to the Earth. How we imagine Earth is a prerequisite to how we narrate and intervene in this moment of crisis.

At DESIGN EARTH, our approach has been to deploy a series of geographically-situated speculative projects, which we collectively refer to as “geostories,” as ways to make worlds both through synthesizing past environmental histories—worlds that have been—and through imagining worlds that might be—not utopian, but not apocalyptic either. Throughout, we have explored different modes of representation and media—triptychs, graphic novels, large-scale drawings, fables, and unfolding murals.

Publications and exhibitions are our primary media of engagement, including the bestseller Geostories (2018), as well as Geographies of Trash (2015), The Planet after Geoengineering (2021), and most recently Climate Inheritance. In our first book, Geographies of Trash, we set up a design research method to engage technological systems—such as waste management, energy, food, etc.—beyond technophilia and technophobia. Technology has a strong social imaginary often coupled with “solutions,” so our work literally follows these systems and visually charts them in order to open up other ways of seeing or imagining them.

Covers for DESIGN EARTH’s publications Geographies of Trash (2015); Geostories (2018); The Planet after Geoengineering (2021); Climate Inheritance (2023).

Take trash, for example, and how the large and complex system of waste management transforms geographies. The question is then: what is the agency of design in shaping the spaces of technological systems, particularly now that the climate crisis has opened the black box of urban externalities? Geographies of Trash situates technological systems in space (to counter definitions of waste as “matter out of place”) by drawing on the allied fields of environmental history, the history of technology, and regional and landscape studies, as well as extensive geographic and urban visualization. Geography affords a way of imagining strong ideological categories or terms—such as “technology,” but also “heritage”—that retain engagement with their spatial, material, and scalar attributes. In that, we drew on Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel’s 2005 book Making Things Public by thinking about how representation is always both a political and aesthetic construct and, by default, is also the space of controversy and deliberation. Representation is how things come to be seen and negotiated in the world—which is to say that a geographic imagination of otherwise foreclosed or predetermined futures makes externalities visible and places them at the center of political life.

This figuring of the climate crisis extends into the recently published book that we are discussing here. By framing World Heritage Sites as its object of inquiry, Climate Inheritance asks: What Heritage and World are possible after the climate crisis? What is the Heritage of the climate crisis?

“By framing World Heritage Sites as its object of inquiry, Climate Inheritance asks: What Heritage and World are possible after the climate crisis? What is the Heritage of the climate crisis?”

It is noteworthy that managers of Heritage Sites are themselves reckoning with the impossibility of current preservation practices, and the limits of their own budgets, in the face of the climate crisis. From the sinking city of Venice to the mass bleaching of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, climate change is drastically impacting some of the world’s most treasured heritages. In an agenda similar to other contemporary UNESCO publications, the 2019 ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) report “Future of Our Pasts” opens with, “The climate is changing and so must heritage.” How does preservation as a practice reckon with the uncertainty and inevitable disorganization of matter that comes with climate events? In the face of the impending crisis, the promises to “rescue” Heritage Sites—to arrest or reverse further decay—are no longer sustainable: frequent, serious material problems lead to costly budgets. Also, the insistence on preserving particular, intrinsically valuable things while the world beyond the property line around them collapses is ethically indefensible. How do we imagine heritage as a practice beyond “saving” and bound between the double crises of the unjust legacies of yesterday and the relics of tomorrow—of critical conservations around heritage and a wicked, negative universality of climate destruction?

“How do we imagine heritage as a practice beyond ‘saving’ and bound between the double crises of the unjust legacies of yesterday and the relics of tomorrow—of critical conservations around heritage and a wicked, negative universality of climate destruction?”

How might we inherit such difficult worlds? In doing so, the book deconstructs “heritage” as a static social keyword with presumed inherent and shared values to point to the unevenness in how values and externalities are distributed in the world. World Heritage Sites become charismatic media figures, or figures of speech, through which to reckon with or utter the unfathomable scale of destruction. From 1,200 World Heritage Sites worldwide, the book casts ten as narrative figures to visualize pervasive climate risks—rising sea levels, extinction, droughts, air pollution, melting glaciers, material vulnerability, unchecked tourism, and the massive displacement of communities and cultural artifacts—all while situating the present moment of emergency within the wreckages of other ends of worlds: of extractivism, racism, and settler colonialism. Each site is presented in a triptych with three drawings and an accompanying text of 500–600 words.

I’d also like to add a disclaimer, which is that we have no formal training in heritage studies or ethnographic research on such sites, but are fascinated by its potential to attract and converge public attention. So I hope that you will consider this with generosity as you discover the bricolage of work, references, and methods.

Images and text from Climate Inheritance on view in the exhibition “Cautionary Tales of UNESCO World Heritage Sites” at Bauhaus Museum Dessau, 2021.

Leen:

Your disclaimer resonated with me as I, too, am new to infiltrating these worlds of historiography and heritage machineries. I approach them from the perspective of a designer and a non-historian, which of course sometimes invites pushback from historians. Nonetheless, I believe it’s important to have a presence in those circles to learn from, and question, the process behind the very histories we consume. There’s an implicit ideological shift that your work seeks to provoke about the climate crisis: that we need to set aside the language of sustainability; that for so long, it has been assumed that there’s a predefined question, yet we never ask ourselves what the question is, or whether it’s the right question. We go straight to proposing and enacting solutions. I see your work as inviting us to take a step back and dare to revise the question. It also dares us to acknowledge the lack of empathy at the root of the climate crisis, and its intersectionality with racism, colonial histories, sexism, and land dispossession. To invite empathy, we need to make this crisis legible, material, spatial, and translatable to laymen, and your work provokes the notion that empathy can be activated by capitalizing on existing frameworks of valuation, such as cultural heritage, and infiltrating various disciplines. Through this process-based approach, what are some of the responses you receive, especially among different audiences? What are the potentials for pushback?

Rania:

You note an important role for the generalist designer in circles of expertise. Experts produce and perpetuate black boxes with presumed values, problems, and predetermined solutions. Bruno Latour’s invitation is to shift the thinking from “matters of fact”—which are presumed stable, transparent, unmediated—to “matters of concern,” which is what happens when politics revolve around disputed things rather than agreement and closure. The political project of making things visible, I believe, operates within an enlightenment-informed modernist way of thinking that assumes legibility and representation will bring about democracy. Beyond that, our work was also informed by the ideas of feminist philosophers, such as Donna Haraway, notably on the importance of speculative fabulation as a mode of evidence that is other than the image of objectivity—of the tables, charts, and graphs that are associated with matters of fact. Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, herself a former student of Haraway, proposes a shift from “matters of concern” to “matters of care.” Such shifts foreground empathy. It’s not just a question of knowing about or seeing something, it’s a question of caring enough about it to want to implement change.

It might be helpful to situate the project within its specific design context. Climate Inheritance is a project born during the coronavirus pandemic and the travel restrictions that brought global tourism and biennales to a halt, creating a sense, however momentary and illusional, of planetary relief and change. Images circulated of wild animal sightings in deserted tourist destinations—of dolphins in the Venetian Lagoon. Even today, when Venice floods, the world reacts with calls to care, donate, and act. The city of Venice has played an important role in the history of heritage, in particular following the record-setting flood of 1966, which rallied an international safeguarding campaign to repair the damages and restore each city’s monuments. This campaign to “Save Venice” was instrumental in the ratification of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Fifty years after the ratification of this convention, the climate crisis has exacerbated the profound paradoxical conception of heritage—the question of which objects to “save” when facing planetary forces of loss and destruction.

Illustration of St. Mark’s Basilica from “Venice and its Lagoon” in Climate Inheritance, 2023. Courtesy of the authors.

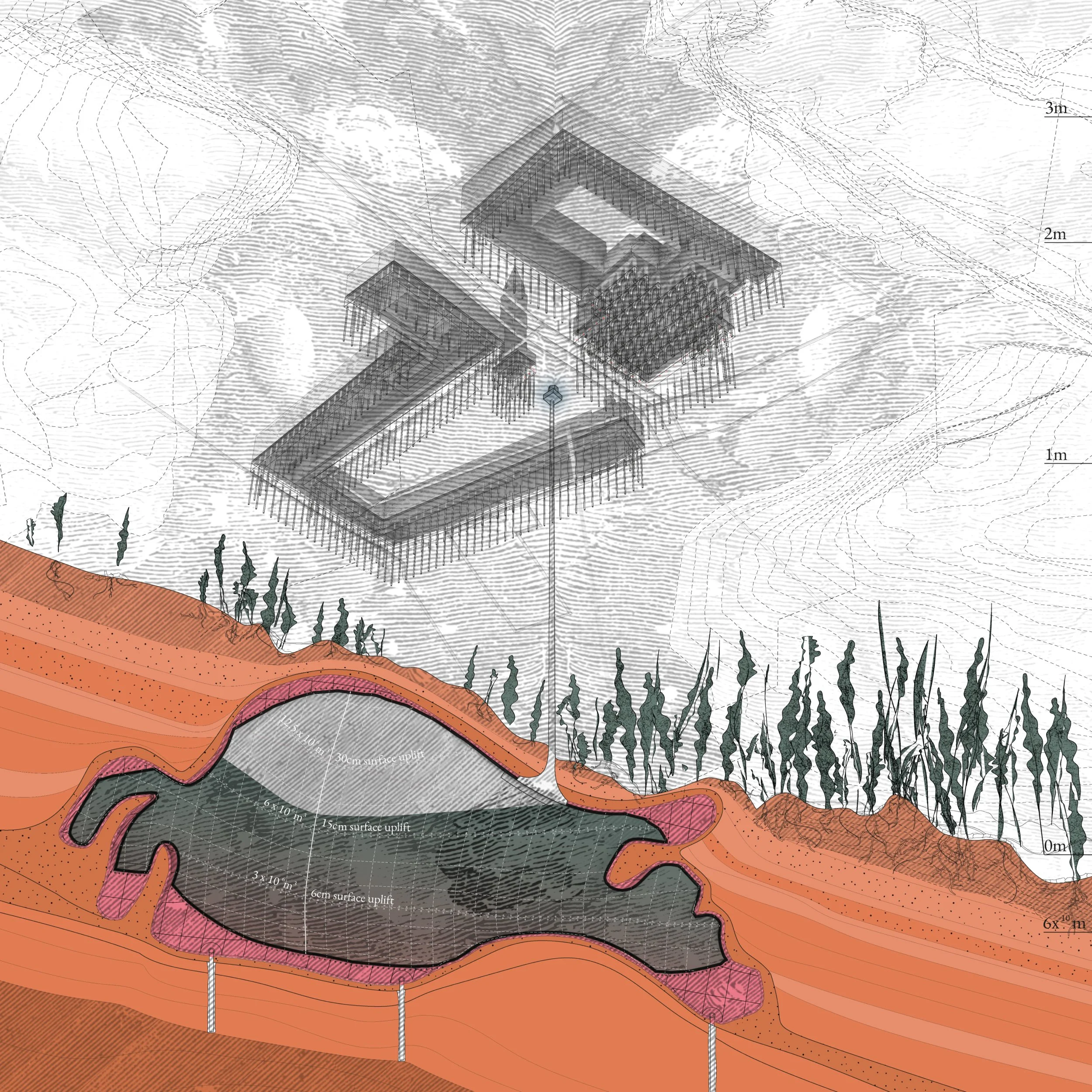

Here, the cover of Climate Inheritance channels the figure of St. Mark’s Basilica to narrate more expansive planetary processes or underground dynamics, such as the depletion of aquifers and soil subsidence, in the case of Venice. The cover drawing is a worm’s eye perspective onto this familiar and cherished monument. The image casts the monument’s aura but frames it from a different view, one which foregrounds the section—with the roots of the seagrass, historic wells, and the underground wooden piles upon which the city rests. The drawing pays attention not only to the historic monument but to other scales and sites of the climate crisis.

Put differently, the media persona of this Heritage Site does work for the world, or at least for some of it. Cultural heritage sites hold planetary media attention. To give another example, the 2019 Notre Dame Cathedral fire made international headlines and philanthropic donations of hundreds of million of euros, getting more media attention and response than the contemporaneous fires that ravaged the Amazon. It was a reminder that attention and empathy are not evenly distributed. But in that media landscape, a Heritage Site could operate like a narrative figure, the tip of an iceberg, to draw attention to the broader underlying climate crisis beyond what is immediately visible. One of the reasons why the Heritage Site appealed to us is the wide circulation of its likeness in the public imagination—photographs, drawings, postcards, hashtags.

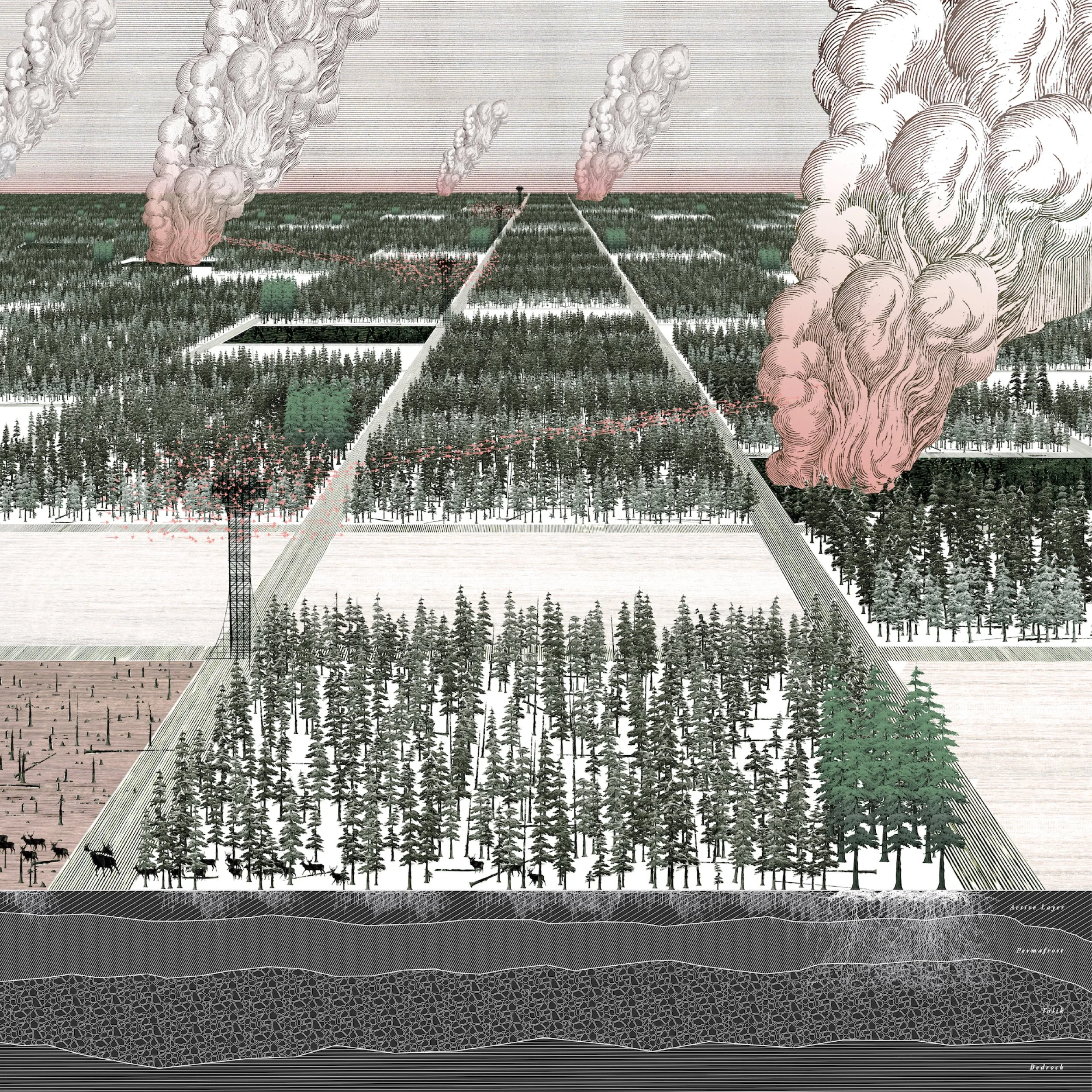

First image: Illustration from The Planet After Geoengineering, 2021.

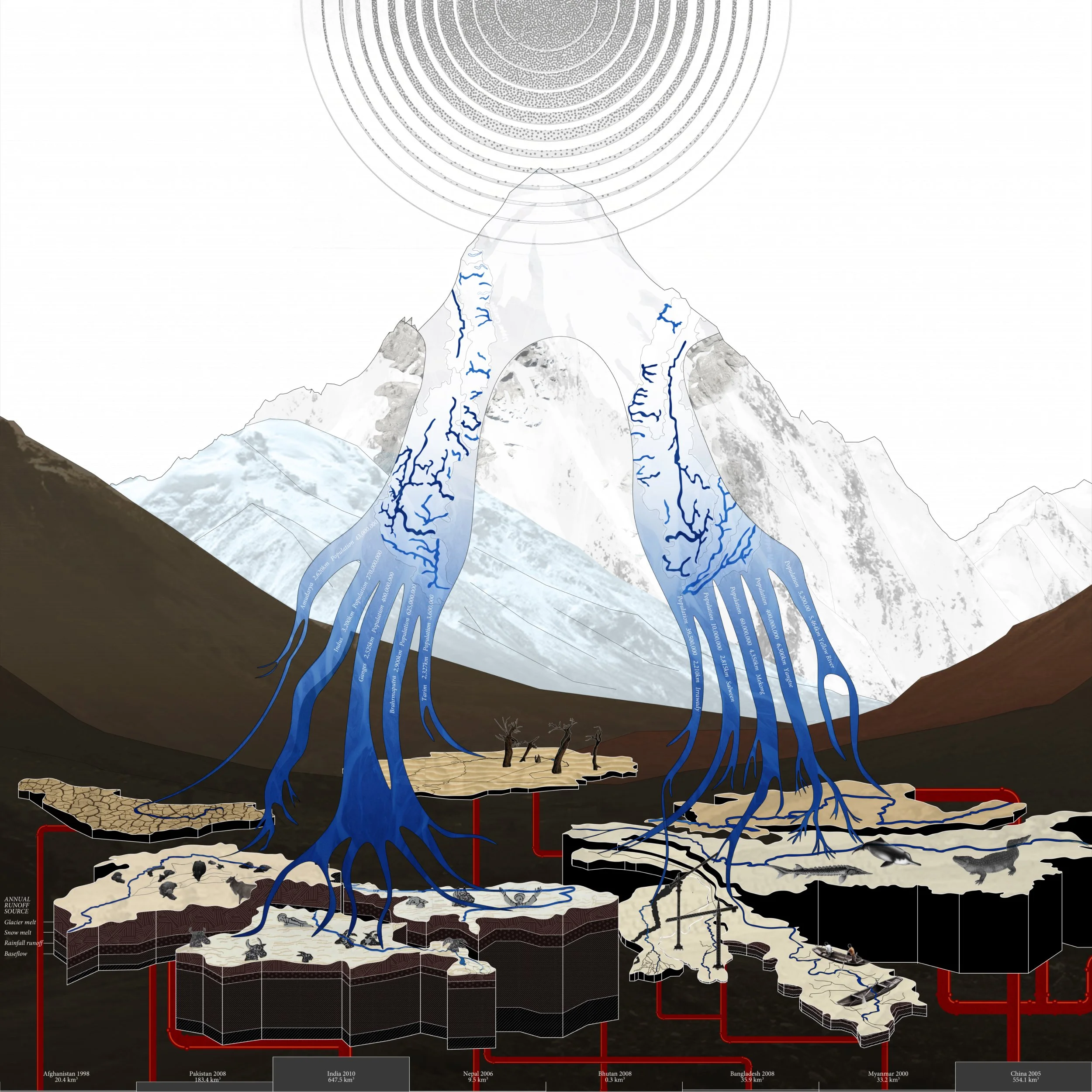

Second image: Melting glaciers in the Himalayas. Illustration from "Sagarmatha National Park" in Climate Inheritance, 2023. Courtesy of the authors.

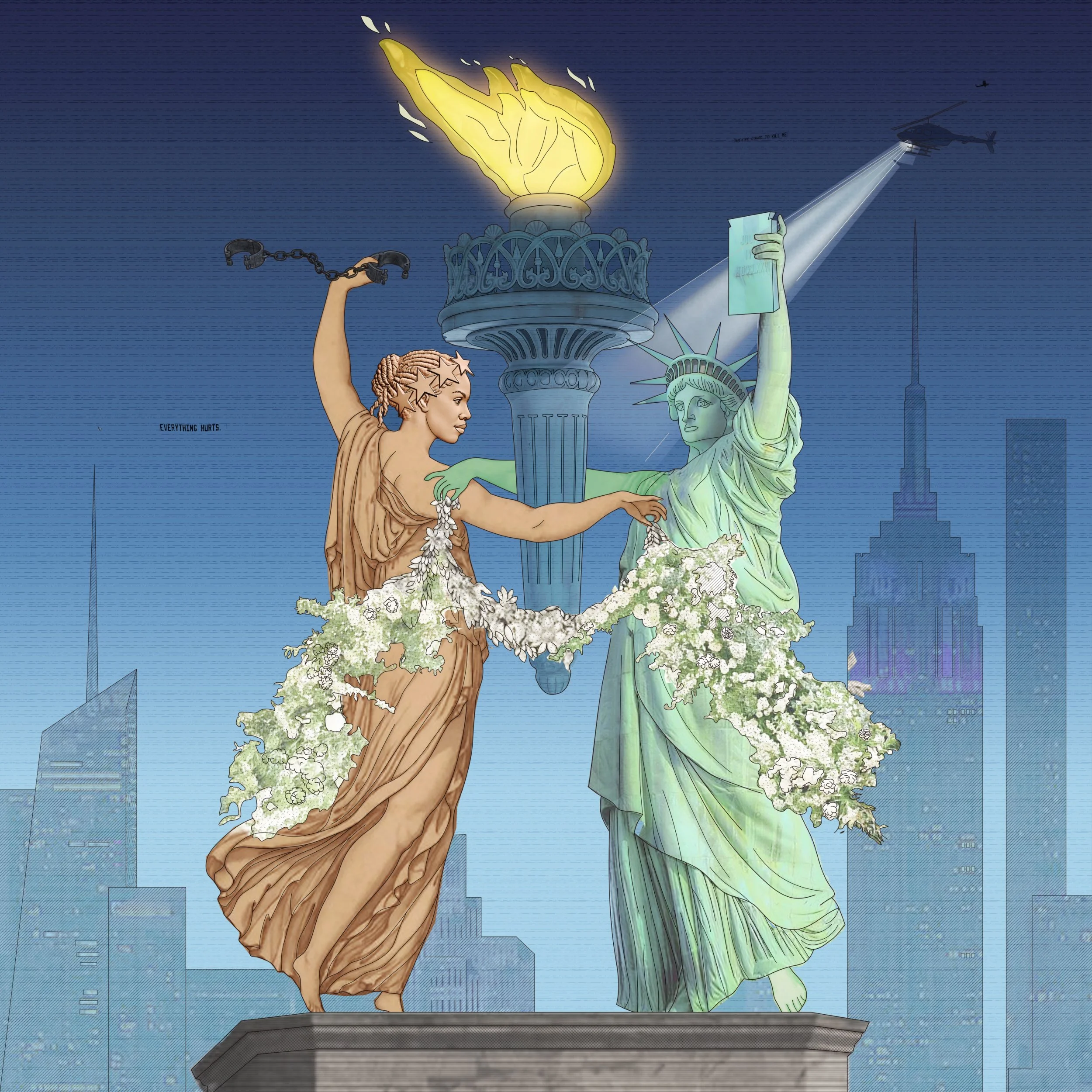

I was reminded again of the power of the monument a few days ago, when Jewish Voice for Peace staged their protest at the Statue of Liberty to demand a ceasefire in Gaza. There’s a visual language to engage power and its representation through the image of the monument. We precisely channeled the iconicity of the Statue of Liberty in another triptych in the book. Can we hitchhike the capital of empathy that is associated with images of Heritage Sites, in order to point to the histories of destruction within which they’re already always enmeshed—the longue-durée of the climate crisis?

The work of Lucia Allais was also particularly groundbreaking for us, especially her essay titled “Disaster as Experiment”—republished in the book—in which she notes how “salvage opens up a suspended moment that tests new ways of shaping forms.” This attention is similar to your own research interest in debris, Leen, in that it recognizes attributes of the built environment that are distinct from the monument and yet deserve their own care—things that might otherwise be dismissed, disregarded, or negatively perceived. Maybe there’s a chance now, at this moment of disaster, for these things to become part of a disciplinary language that explores their value or understands their matter—makes them matter—as elements of design. We draw on the work of critical heritage scholars Colin Sterling and Rodney Harrison, as well as Caitlin DeSilvey, to rethink the care of such sites in terms of ecology, aesthetics, and politics. Broadly speaking, this is also what David Gissen has achieved beginning with Subnature: Architecture’s Other Environments (2009), and his work on experimental heritage is also published in Climate Inheritance.

As you rightly pinpointed earlier, the climate crisis is an intersectional crisis. Climate histories, presents, and futures are inevitably bound up with questions of political economy, of cultural relations, and the stories and mythologies that have been told about climate. And, of course, climate destructions have been unequally distributed. Whole worlds have already ended, sometimes multiple times over, so it’s important not to cast it as exceptional or futuristic. Even for some of the sites that we explore in the book, the climate crisis is already a historical event. So how do we weave together these temporalities? And, to get back to your question, what are some controversies that may come about with this approach?

Affiliates and allies of Jewish Voice for Peace at a secret emergency sit-in at the Statue of Liberty on Monday, November 6, 2023. Image courtesy of Jewish Voice for Peace.

“Climate histories, presents, and futures are inevitably bound up with questions of political economy, of cultural relations, and the stories and mythologies that have been told about climate. And, of course, climate destructions have been unequally distributed. Whole worlds have already ended, sometimes multiple times over, so it’s important not to cast it as exceptional or futuristic.”

Leen:

I agree that there is great value and intelligence in moments like, as you mentioned, Jewish Voice for Peace specifically choosing the Statue of Liberty as a site for protest. It’s a way of infiltrating a site that has an already established cultural value and aura surrounding it. Because of that brief moment, the protest will forever become part of the site’s history and narrative.

You mentioned that the book covers ten sites and that you’re inevitably framing very specific histories of these sites. Even when we think about the drawing of Lady Liberty, all these moments in time converge into one version of the site’s history. In doing so, we forego, at least in the context of the book, the multitude of ways that we could assess and reassess the history of a place. Within this process of hacking pre-established value systems, we’re accepting the paradox of preservation: that one version of the site’s history is overwritten and erased by another.

Rania:

The Heritage Sites become narrative devices, or maybe we use the word “figure” as in to figure it out, but also a figure as in an outline or a drawing. Donna Haraway thinks of the string figure as one way to be in dialogue through the practice of continuous unfolding and re-weaving, all of which uncommons the assumption that “the world” cares about a site, or ought to care about it, precisely because, often, conversations around the climate crisis—particularly the idea of the planetary imaginary—speak about a very ambiguous “we”: a presumed shared future in which everyone might be served. Part of uncommoning histories is also uncommoning futures. Historically, “we” has not necessarily spoken in the name of everyone, or even in the name of a majority, but has involved particular private interests. These interests have come at huge public costs borne by various people, spaces, materials. If we’re not mindful to always ask who’s standing behind the “we” of the “world” in climate responses, then these solutions may be at risk of perpetuating similar systems of dispossession to those that got us into this mess to begin with.

Thinking through heritage unravels how its construction as a system of shared belief or value has often also meant the destruction of other worlds and values—removing existing settlements, purifying monuments, or even curating life. In Climate Inheritance, we push back against the universalism and anthropocentrism of “world” and “heritage.” Let’s take the example of the Galápagos Islands National Park Service ecological restoration program, which has supported the rewilding of “valued” tortoises by eradicating predatory animals—introduced by colonial settlers and now labeled “invasive species,” such as goats, feral pigs, and donkeys—by ground hunt, sharpshooting, and poison-laden mini-helicopter drones. In particular, the Judas goat technique consists of capturing one animal from the herd and tagging it with a GPS device, after which it is released back on the island and tracked back to the herd, which is gunned down, except for Judas. Track, kill, repeat. The last sterilized Judas goat is allowed to live out the end of their days on the island, haunted by the effects of such repeated trauma. In this triptych, we reckon with how forms of life are valued and curated in history and in preservation. We revisit and adapt the schematic drawing of the slave ship Brooks (also known as the Brookes) to portray the cohabitation of human and environmental destruction: of the inhumane living conditions that enslaved Africans endured during the Middle Passage and of the Judas goat technique in contemporary ecological restoration.

Speculative narratives are in part a revisionist history and in part projective futures that neither shed the tensions of the past nor seek resolution. They don’t iron out all the contradictions and unevenness of the world in pursuit of a “fixed” future. They’re actually saying—let’s stay with those challenges for a bit. If Lady Liberty’s promises are not yet fully realized, then the horizon of that political project is still necessary.

Speaking of context again, as we were working on this project during the first year of the pandemic, the number of deaths in New York City was glaringly racialized, as was the geography. When thinking about the Lady Liberty triptych, the challenge is to see her failings but without letting go of her promises. Think literally about her color, which is a patina—a transformation of copper because of the changing environment and upkeep. From all of the issues that one might address with respect to the statue, the question of the color line emerges as a primary concern.

Illustration from “Statue of Liberty” in Climate Inheritance, 2023. Courtesy of the authors.

Leen:

Regarding the role of color in Lady Liberty’s history and how it became a matter of care and concern for the public realm: you begin with a narrative and drawing, on page 61, that show various “color lines” demarcating the evolution of the statue’s materiality from brown copper to a green patina due to pollutants. In a way, you then subvert that material history by placing it against present-day forms of color lines that are less materially perceptible and have drawn less empathy from the public, like the disproportionate proximity of people of color to polluted sites. There’s a conscious choice in this section of your book to use the term and representation of a color line to describe Lady Liberty’s material history and its original intent to celebrate the end of slavery. You carefully tease out that history, and the aura surrounding it, to shift the color line to a present-day agenda for climate empathy that calls attention to less perceptible yet enduring forms of racial inequality and segregation, which I find provocative.

Illustrations from “Statue of Liberty” in Climate Inheritance, 2023. Courtesy of the authors.

Rania:

That’s very generous. The speculative fictions were indeed quite condensed. The preliminary work is extensive, compiling a research dossier of “facts” on each site—visual and textual citations as well as various cultural representations. Then, each speculation fiction compresses facts to a critical point which, when inserted into the world, becomes a tale or a fable that speaks truth to power. The book presents the final drawings, but one can imagine a layout or book design that expands again to be more transparent about the process and its sources. This is a good experiment and challenge to take on for the “Elephant in the Room” fable series that we are currently working on.

Leen:

Could you describe what it would look like to make all of that available? To set the stage for multiple variations or assemblages, some of which are the images and text that you present? What might be the productive outcomes or limitations of such democratic engagement, if we can refer to it as such?

Rania:

In a conversation with Sylvia Lavin around this book, she picked up on the use of the word “charismatic” in the text. And, as she beautifully does, she traced an etymology of that term, eventually tying it to the casting of a spell. To me, you’re asking for a peek into the magician’s sleeve so you can figure out the tricks. If you explain the spell for the sake of knowing, it won’t work as well. Like when you find out that the coin was on the back of the magician’s hand all along. This work is very aware of its performative quality. The question here is less about transparency, or demystifying magic, and more about training future magicians to cast their own spells, world their own worlds.

Leen:

This is the problem of what the “worlding” in world heritage allows for. I think you might enjoy Graham Jones’s book Trade of the Tricks (2011). It’s an anthropology of magic that delves into the question of perceiving the trick versus knowing its underlying machineries.

Rania:

Historical memory glimpses over certain inheritances, or at least there’s a very uneven distribution of attention to questions that matter very much to some and not as much to others—such as how wealth is built through dispossession—as is the case of the settler colonial project on Turtle Island. There is sometimes a sense that we don’t have a choice in what we inherit—that we’re thrown into it. But what we make out of what we inherit is always an open question. What will we do with what we receive, and what will we bestow to future generations? This is an open political project.

“There is sometimes a sense that we don’t have a choice in what we inherit—that we’re thrown into it. But what we make out of what we inherit is always an open question. What will we do with what we receive, and what will we bestow to future generations? This is an open political project.”

The only way to imagine the future is by reckoning with the ghosts of the past. This is particularly true for the energy paradigm. After World War II, energy use became the United Nations’ key indicator of development, with a strong correlation between economic growth and energy use. Today, the imperative to respond to the climate crisis calls for an immediate wind-down of fossil fuel use towards a green “energy transition.” The “renewable” solution, however, is not further extraction, such as that of lithium from the Atacama Desert in Chile. The change in the energy source or energy carrier is not necessarily a shift in paradigm; it doesn’t unworld the systems of dispossession and negative externalities upon which the current crisis rests. In such cases, it only furthers the unevenness that is accumulated. All acts of worlding anew are necessarily acts of unworlding.

Leen:

This is perhaps an opportune moment to segway into the role of the section drawing, which figures prominently throughout Climate Inheritance and the larger body of your work to reveal the underlying workings, and unworkings, of the climate crisis. Can you expand on the generative potential of the section in your work?

Rania:

The section is indeed a favored representational technique of ours. Drawings are arguments about the world. The section drawing, for instance, counteracts the abstract earth of aerial mappings, as seen from above, to touchdown. Rather than a detached hovering view, a section is always grounded, geographically situated in a specific site and in a measured way. The section counteracts a knowledge of Earth as relegated to separate earth sciences to advance ways of knowing across disciplines, to establish vertical relations between various domains of the Earth, both above and below the surface of the water or ground, and it does that across temporal and spatial scales from geology to material details.

Illustration from “After Oil” in Geostories, 2018. The height of architectural towers in the United Arab Emirates are indexed in relation to geological depths and timeline of oil extraction. Courtesy of the authors.

Leen:

I’d like to bring up an important quote from page 19, on which you write: “The work of inheriting responsibly, particularly when what needs to be inherited is a difficult history, is also a work of warning and of bearing witness at sites of violence. This task requires the humility to dwell with traces of loathed history, and the ghosts of wretched earths.” I found that to be very powerful in the moment that we’re living through now.

Rania:

How do you record an ancestor’s life? How do you write their life sketch if they lived as a figure at the threshold of respectability? And how do you live with that inheritance? How do you mourn, if only to speculate other possible afterlives? We really need to figure out what we can salvage so that we, and our descendants, can also have life. Being able to frame the future as positive is an ethical responsibility. One can easily collapse into despair, except when one is reminded that, politically, there’s no such choice. So we must choose to pass down life in metrics that might not be currently registered.

“Being able to frame the future as positive is an ethical responsibility. One can easily collapse into despair, except when one is reminded that, politically, there’s no such choice. So we must choose to pass down life in metrics that might not be currently registered.”

Leen:

bell hooks also talks about the importance of reaching back to past forms of oppositional practices and connecting them with present forms of resistance as part of a continuum.

Rania:

That’s the only way to rescue the future. We need to rescue the future from its utopian promises, and we can do that by situating moments of transformation and revolution within the past, by contaminating the future with the ghosts of the present and the past. In doing this, we remove ourselves from the technocratic worldview in which technology will bestow the solutions to our problems and then we will live happily ever after. The fairy tale of technology has never been true. It’s just another story that keeps getting repeated.●

Illustration from “Ilulissat Icefjord” in Climate Inheritance, 2023. Courtesy of the authors.

Rania Ghosn is Associate Professor of Architecture and Urbanism at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and founding partner, with El Hadi Jazairy, of DESIGN EARTH. Their design research practice employs the speculative architecture project as a medium to make visible and public the climate crisis. They are authors of Geostories: Another Architecture for the Environment (3rd ed. 2022; 2018), Geographies of Trash (2015), The Planet After Geoengineering (2021), and Climate Inheritance (2023). Ghosn is recipient of the United States Artist Fellowship, the Architectural League Prize for Young Architects + Designers, the Boghossian Foundation Prize, and ACSA Faculty Design Awards.

Leen Katrib is Assistant Professor of Architecture at the University of Kentucky. Her work investigates architecture’s materiality and historiography and designs new frameworks for marginalized histories and material culture. It has been supported by Art Omi, MacDowell/NEA, Harry der Boghosian, and P.D. Soros fellowships, and Howard Crosby Butler, William & Neoma Timme, and George H. Mayr travel grants; published in Future Anterior, Pidgin, Room One Thousand, and Bracket; exhibited at Lexington Art League, Syracuse University, Van Der Plas Gallery, the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, and A+D Museum.