Beyond Crisis: Finding Beauty and Purpose in the Climate Future

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson

in conversation with Mark ChambersPhotography by

Guarionex Rodriguez, Jr.

This interview was conducted on

October 10, 2023 in Maine.

It has been edited and condensed.

MARK CHAMBERS:

Thank you for having me at your home.

AYANA ELIZABETH JOHNSON:

Thank you for coming.

Mark:

Let’s have a meandering conversation, if that’s okay with you.

Ayana:

Always preferred.

Mark:

I’d like to begin with something you brought up the last time I saw you, which was a couple of days ago, at an exhibition you curated, “Climate Futurism” (October 6–December 10, 2023)—with commissions by artists Erica Deeman, Denice Frohman, and Olalekan Jeyifous—at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn. One of the reasons why I was attracted to Deem, and to being a part of this issue on climate responsiveness especially, is that while each Deem issue is, in ways, a highly curated anthology on a topic, it’s also a love letter to designers of all kinds and an invitation to its audience to see themselves as designers. Now that you’re in the role of curator, do you see your “Climate Futurism” exhibition as an invitation? Do you see it as a love letter and, if so, who is that letter to?

Ayana:

It is absolutely an invitation. I think that is a word that describes most of my work, because the climate challenge is really a question of, “How do we get everyone engaged in finding their role in solutions?” Looking back on my work of the last few years, it’s been many different iterations of extending a hand, and trying to say, “Welcome.” This show is the most recent public iteration of that. It is a visualization of answers to the question: “What if we get it right?” That question has been driving my work for a long time, but I only noticed quite recently that it has been my framework, once I had to come up with the title for my forthcoming book.

There’s so much in the world that’s overwhelming and depressing, and there’s so much that’s wrong. By constitution, I, and most people, can only sit in that dystopian present and future vision for so long before it’s really demotivating. Yes, things are bad. What do you do with that? I don’t even need to read all the climate science reports to tell you that it is worse than you had imagined. It is going off the rails more quickly, and in more intense ways. Climate scientists projected all of this, but to see it play out at this speed and magnitude is very overwhelming.

But if we actually charge ahead with all of the solutions we already have, what do we get? I think a lot of people can’t picture what a good version of the future is like, and so we’re all just meandering around, sauntering away from the abyss, away from the precipice. What’s missing, what’s powerful, is having something to run towards. I want my work to say, “Welcome. There are solutions. In fact, we already have most of the solutions we need, and we need you to be a part of manifesting them in the world.” We need everyone to find their role in implementation, which is a word that I’m obsessed with.

Mark:

It’s a good word.

Ayana:

It’s so sexy. Who’s going to make this real? Who’s going to turn this from an idea, or a proposal, into an actual transformed economy, society, and culture? That is very exciting—the thought that each of us could help build the future. Of course, most people don’t know where they fit into that, because all of our messaging has been, “The climate apocalypse is nigh,” which it is. But we still get to shape what the future looks like, and there is still so much possibility, and agency. “Climate Futurism” is an invitation to artists, and to the public, to start to think about this question in more generative ways. That’s the vibe. I’m not a rage-against-the-machine type. I’m like, let’s just build the thing that we want.

“Who’s going to make this real? Who’s going to turn this from an idea, or a proposal, into an actual transformed economy, society, and culture? That is very exciting—the thought that each of us could help build the future.”

Mark:

There is a certain optimism aligned with a solutionist mentality, which I think is something that is particularly needed right now. The pessimism and temptation of gloom and doom is, in a way, appealing because it’s easier to do nothing and just watch everything continue to fall apart in front of us.

Ayana:

It’s so easy, because it’s all true. I’m not an optimist, by the way—I’m a scientist, a realist. And we’ve seen how humans have this proclivity to tear each other apart. That’s what this is really about. Can humanity get it together—yes or no? Can we do it in time? I have a hard time being optimistic, given human history, but it’s not all or nothing, which I think can get lost in discussions about climate in particular. There is a full range of possibilities, and the difference between zero and 100 is huge. Could we get to 80? I’ll take 80. Hell, I’ll take 60 at this point, but we can’t just settle for zero. The stakes are so high. Hundreds of millions of lives, if not billions, hang in the balance.

Mark:

Then it becomes a question of who gets to participate in that future, even in that 60–80?

Ayana:

Who gets to shape the future? Who benefits from clean air and water? Who has access to regenerative organic food? Who has green buildings to live in? All of that.

Mark:

Shaping the future, as you mentioned, will require us to be able to picture what we’re running towards. Artists have always had a great way of helping us see around corners and I think that the artistic practice of visioning is sorely missing in a lot of climate conversations. Do you consider yourself to be an artist?

Ayana:

My mom once said that I have the soul of an artist, and it was one of the nicest things she’s ever said to me. I’m honored by the thought, and the question. But I think being an artist involves making art, just like how being a writer involves writing. There are so many people who think of themselves in these terms, but who are not actually involved in the practice and the processes that come with either. I do have a lot of aesthetic opinions and I care about design. I’m so pleased to be a part of Deem for that reason, because not only do I want us to create a transformation that allows humans to keep living safely on this planet, but I want it to be beautiful. I want climate adaptation to be beautiful, and there’s no reason that it can’t be.

Mark:

Absolutely. Beauty can be a powerful driver in so many ways. It can be a catalyst for the protection of things we value and it has great potential to teach us about quality in the solutions we design.

Ayana:

It’s another way of saying welcome. “Welcome to this beautiful smorgasbord of climate solutions.” But beauty has to be paired with other things. One of those is durability. I think part of how we start deliberately building things to last is through truly valuing things because they’re beautiful. It’s a virtuous cycle. So much of the problem of our environmental crises is disposability, whether that’s plastic water bottles or buildings. We just don’t build things to last anymore. You cannot repair things. You have to buy new things. Planned obsolescence is ugly, and it’s killing the planet. It’s a lose-lose.

Mark:

100%. I have little interest in ugly solutions. Often, something we find innately beautiful might actually resonate with us simply because of how good it is at problem solving. It can be elegant. And, by the way, I’m not going to let you get away from considering yourself as an artist. Writers are artists and I think it’s incredibly important now more than ever to use words not just in creating a vision, but to fill in the blank space of how we’re supposed to creatively interpret that vision and this transition. And, speaking of writing, I also have to warn you, I consumed a possibly embarrassing amount of Ayana-related literary content in advance of this conversation and believe that one of your artist-specific qualifications is chapter two of your PhD dissertation—

Ayana:

What’s chapter two?

Mark:

Let me help you out here. [Mark sketches on a notepad]

Ayana:

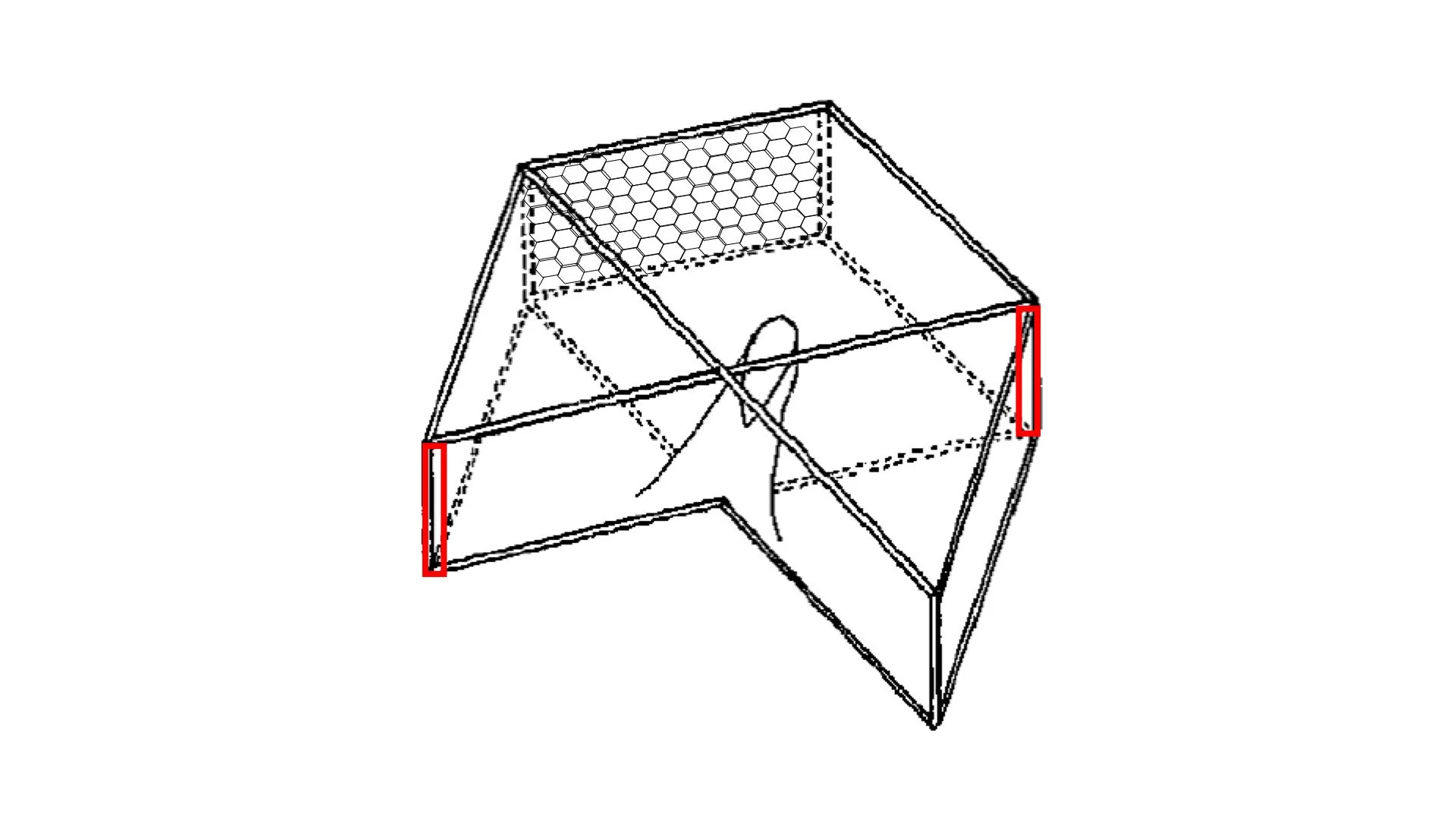

The fish trap? The chevron-shaped fish trap?

Mark:

See, I know what I’m talking about.

Ayana:

That’s a deep cut. I appreciate that.

Mark:

I don’t fully understand the trap’s functionality, but I appreciated the logic you expressed around why you designed it.

Ayana:

It’s so simple.

Mark:

Could you tell me about it?

Ayana:

I was in graduate school and I went down to Curaçao to be a dive buddy for a friend who was researching coral reproductive biology. While I was there, I met this incredible man, Faisal Dilrosun, who was leading the fisheries department. He told me they were thinking about developing new fishing regulations, and were considering a rule that would require including escape slots in fish traps—basically, holes in the corner that would let baby fish and small ornamental fish species escape.

But they weren’t sure if the slots were going to work; they had never tested them. I said, “I can test this for you.” So Faisal introduced me to a fisherman who made traps. And I went to the hardware store to look for materials for fabricating the slots and realized we could use rebar, welded into narrow rectangles. We tested multiple sizes to see if the small fish would be able to get out. The idea was that you could just stick a slot in the corner of an existing trap, and it would be like fifty cents each to modify them, with materials anyone could access.

It took like 300 scuba dives on four different reefs to prove, rigorously, that it worked and, importantly, wouldn’t hurt fishermen’s incomes since they weren’t selling the tiny fish anyway. I was doing three or four dives a day for months. I was soggy, cranky, and cold. But, in the end, I was able to share the data with the fisheries department, and they said, “This works; we will make this the law.” That was such a fascinating moment for me, because I had pursued a PhD in marine biology to be useful, and to change policy, and I did just that before I even graduated. It was a small thing—

Mark:

But an elegant one.

Diagram of a fish trap with escape traps. Courtesy of Ayana Elizabeth Johnson.

Ayana:

That’s what I loved about it. People said, “You invented a fish trap!” I’m like, “I literally put a hole in the side, but fine.” They’re like, “Are you going to patent it?” I’m like, “No, I want everyone to use this for free. Take my idea, please. You don’t have to cite me, you don’t have to pay me. But if you could save some baby fish, that would be great.” It’s now required by law on other Caribbean islands, too. And a leader of the East African Office of Wildlife Conservation Society saw me give a presentation and started developing and testing them in Kenya and Tanzania. The whole experience was a lovely example of how one can be useful. This came about because they told me what they needed, and I was like, “I can do that.”

I feel like, so often, design is not solving a problem, and it’s not answering a question. There’s a lot of indulgence and ego in this discipline and—if I may be a bit rude about it—we don’t have time. It’s also just so gratifying, too, to be useful in the world.

Mark:

Design is the process of adding value, right? Ideating, iterating, prototyping, testing, putting into the world.

Ayana:

Okay, but this question of, am I an artist? I would still say no. I hold art in very high regard. I don’t want to take credit away from the people who are really in that. I might, self-aggrandizingly, half take on the title of designer, if only because I am extremely thoughtful and deliberate about what I release into and share with the world. There’s so much embedded in how we present things, not just what we present. Sometimes, I think to myself, if only the climate movement had cared more about design in its early days. We might’ve welcomed more people in sooner. It was just raggedy dirty hippie, which is not everyone’s vibe.

Mark:

No, it’s not. And it can be very exclusive, but not in a good way.

Ayana:

That’s something that has changed so much in the last five years as graphic design tools have become more accessible. I’m seeing much more appealing presentations of climate ideas. More people are like, “Okay, I could affiliate with that. I could see myself in that. I could repost that.”

Mark:

I do think it also helps to have a hopeful concept and perspective that people can get behind.

Ayana:

I have a whole chapter in my book about my relationship with hope. Well, it was a whole chapter, but it got cut down to, like, two pages. My editor more or less said: you can’t just shit on hope for an entire chapter. People are extremely into hope.

The word “hope” has two different origins. One is expectation, and one is desire. While it’s unreasonable to expect that everything’s going to be fine, it’s very reasonable to desire things to be better. But an optimistic expectation that the outcome will be good, no matter what, is naive to the point of being counterproductive. It can be as demotivating as doomerism. What I want to know is, “What’s the plan? Who’s doing what? What’s the strategy?” Forward motion driven by a desire for a different reality.

Mark:

That need for forward motion is an important impulse in this conversation, and in Deem’s mission—the idea that design, and perhaps design thinking, belongs to everybody. Or that it could.

Ayana:

What does design thinking mean?

Mark:

It’s a bias towards action and learning by doing. So it kind of comes from a design studio environment, where success for a project or for a team is based on an ability to rapidly prototype and do tons of iterations on solutions to help you challenge your original assumptions quickly, and get to better results and better beta versions of your solution quickly. You then really get in the habit and practice of learning by doing. That’s how I think about it. For me, as an architect and three-dimensional problem solver, I always learned the most by creating something and then looking at it from different angles until I truly understood what I had. And I guess I think it’s an important process for different types of problem solvers to consider using, because there is a special power in the actual doing, and a special power in the making of things. It’s back to being about implementation, right? Like... I’m 100% all in for a maker’s renaissance. Can we just champion the makers right now? And help them tackle this challenge? I mean, do you think about climate change that way? As a design challenge?

Ayana:

It’s entirely a design challenge, and it’s a physical one. We have to physically transform our world. Being based on fossil fuels is a massive infrastructure choice and investment. If we want to switch from a fossil-fueled, extractive economy to a regenerative, renewable economy, that is a physical transformation. 75% of the infrastructure that will exist in 2050, and that is needed for that switch, does not exist today.

A big part of the evolution of my own thinking about our relationship with the earth has been understanding that we don’t want to live on top of nature. We want to live with nature, but actually we want to live within nature. Trying to find humanity’s role within the ecosystems of the planet, again, is a huge challenge because we have to redesign basically everything—like, everything: our supply chains, our supermarkets, our transportation, our homes, our energy systems. Everything needs to change. Sometimes I wish people saw more of the potential in that because there are so many decisions to be made about how we will live. We should want to participate in those decisions. Don’t be mad that the people who designed the world we live in now didn’t do it the way you wanted if you don’t want to help out now.

“Trying to find humanity’s role within the ecosystems of the planet is a huge challenge because we have to redesign basically everything—like, everything: our supply chains, our supermarkets, our transportation, our homes, our energy systems. Everything needs to change.”

I also hope that there’s a renaissance around valuing trades such as carpentry, plumbing, electrical work, metal working, etc. In the US, we really undervalue vocational skills. It might sound corny to say, but there’s so much opportunity in the simple fact that this work has to happen. Despite everything, we’re still doubling down on fossil fuel infrastructure: new pipelines being built, new refineries. Yet, at the same time, we have this incredibly rapid ramp-up in renewables and transitions in the way we build. I mean, the fact that concrete is 8% of our carbon footprint is bananas. But there’s a reason it’s such a “convenient” building material. There’s infinite space for creativity in this transition. We need designers. We need people who are physically making and remaking the world. We need to value that, instead of…

Mark:

Profit maximization?

Ayana:

And academia and degrees and titles. It’s like, but can you grow me a tomato, regeneratively? Can you insulate my attic? Can you figure out geothermal? All of these challenges are so critical and also frustrating. They are iterative and will require trial and error. I think the word that I keep coming back to is actually gratifying. To do these things well in the world is so gratifying. This is not miserable work. It is gratifying, if not glorious.

“All of these challenges are so critical and also frustrating. They are iterative and will require trial and error. I think the word that I keep coming back to is actually gratifying. To do these things well in the world is so gratifying. This is not miserable work. It is gratifying, if not glorious.”

Mark:

Absolutely. And part of that speaks to there being all these thorny and intertwined systems at play that make overcoming challenges appear impossible, or too cumbersome. I think one of the things that needs to shift is how willing we are to adjust our perception of what can change and how.

Ayana:

We have all these existing structures and materials. What are we going to do with them? What can we reuse? As the daughter of an architect, that’s one of the things I’m most excited about. There are new building codes in some cities that say you can’t demolish, you must deconstruct. You can take apart buildings and reuse their parts.

I think everything we design should be able to be taken apart. It should all be like Legos. Speaking of, Legos were going to start being made from recycled plastic. And then they decided it actually didn’t make sense because of the energy investment in switching the plants and manufacturing, blah, blah, blah.

Mark:

We are sometimes just so unwilling to try harder.

Ayana:

There has to be a way.

Mark:

Part of the work is being willing to actively recognize which assumptions we took for granted in the old model, and which constraints we accepted. I keep thinking about this idea of gratification, of satisfaction. The future we are designing needs to feel good. We tend to ask what the future should look like. And I think that’s something that a lot of people are working on, and that’s fantastic. But what do you think it feels like? What do you think it smells like?

Ayana:

There’s a word for the smell of the earth when it first starts to rain. Petrichor. That’s what it smells like. And problem solving.

Mark:

There are, however, burdens that come with being useful. How do we find time for rest amidst the urgency of this hard work? How do we find ways to take turns, to help each other up?

Ayana:

It’s a relay race. By way of a story, my father always thought I was very overscheduled as a child. He was worried that I didn’t have enough time to think and be creative in an independent way. There’s another tangent within that tangent. My father was an architect: a Black Jamaican immigrant who went to Pratt and had two degrees, one in architecture and one in urban planning. He came from a working-class family. I found out after he passed away that there were times when he was eating free saltines and ketchup packets from the salad bar, just trying to get through to the next day. But he knew his calling was architecture.

I also found a letter from one of the partners at a firm where he worked about a loan to help him with the next term’s school fees. So there were people who stepped in to help along the way. He, like many architects, had a healthy ego about his ability to design things. But he never really got the chance to fully express his creative power—to design buildings he could point at and be proud of like, “I made that.” He, with two other Black men, had a firm in Manhattan in the eighties and nineties. They were three partners and did mostly small projects for the city, and it always took forever before they got paid. It was awful.

Mark:

Yeah, I hear you. Architecture is a very tricky profession. You said your father felt called to it and I think that’s in part because there is something magical about getting to imagine and then craft the spaces where our lives unfold. There’s nothing quite like it, even if you just designed a lobby in a building and can’t claim the whole building as yours. It still feels exciting. But I think the duplicitous part that no one really talks about is that that feeling alone doesn’t pay the bills... definitely not the same way it would if you were the engineer or construction contractor on that same building. So it’s tricky, because the architect may get the prestige, but they still get paid last and least.

Ayana:

And, of course, on top of that, it’s an extremely insular and racist field. To this day, only 2% of architects in America are Black. I’m embarrassed to say that, for most of my life, I sort of thought my dad was a failure because he hadn’t achieved the money or the accolades or the big fancy buildings. A few years back I was at this cocktail party and a bunch of architects were there. I’m chatting with a middle-aged Black man. He tells me he’s an architect. I say, “Oh, my dad’s an architect.” He’s like, “At what firm? What did he do?” I tell him and he says, “I’ve heard of your father. He opened a lot of doors.” So I’m crying at this cocktail party, because I had missed the entire fucking point. It’s not about the glory. It’s about the ripples. None of us know what the impact of our work will be. But if you’re doing it for the right reasons, you just suspend your disbelief. Maybe this is where hope comes in.

Ayana’s personal record collection, mostly gifts from her parents.

“It’s not about the glory. It’s about the ripples. None of us know what the impact of our work will be. But if you’re doing it for the right reasons, you just suspend your disbelief. Maybe this is where hope comes in.”

Mark:

I’ll respond to your story with another story. I’m one of those 2% of architects who are Black, licensed, and practicing in the US. When I started working, it was for a Black-owned architecture firm in Washington DC that I had seen in an article in the Washington Post because they were responsible for the first major downtown corridor building that was designed by a Black-run firm. And as people did in the days of old, a friend of mine cut the article out of the actual newspaper and sent it to me in the mail.

Ayana:

What year was this?

Mark:

This was in 2000, maybe. I went to DC and made an appointment to go talk to these folks. They looked through my portfolio and were like, “This is fantastic. We’re not hiring—but—we know it’s very difficult to be a Black dude working in a predominantly white male profession. So, tomorrow, come in and spend the day, see all the stuff that’s going on. If you want to work on anything, you can take whatever you touch for your portfolio when you interview anywhere else.” I ended up coming back for five days in a row until they found a way to offer me a job, but that’s not the point.

My point is, there’s this cadre of Black architects that I, too, have a very intense emotional gratitude for because I know it is a bizarre and oftentimes thankless profession. And, it’s this notion of ripples, of opening doors, that drives the stories that end up being particularly profound in the arc of our individual journeys. That itself is a legacy worth protecting. And speaking of legacies and ripples in the water of this generational work, have you given a lot of thought to your own legacy?

Ayana:

Thank you for sharing that. On this question of opening doors, my intent is to do work that is an invitation and a welcome.

I’m always astounded by the number of people who tell me that things I have done—like my TED Talk—or written, have impacted or changed their life. Of course, I hoped that people would find it and make something of it, but somehow the best-case scenario is actually quite overwhelming. Like, I don’t want to be recognized. I want to make my offerings and then… disappear into the trees.

Mark:

But you’ve learned that’s not possible.

Ayana:

That’s why I literally bought this house in the trees. I’ve definitely created more ripples than I ever thought I would. And I think this is why I feel comfortable with being middle-aged, at 43, because I feel I’ve used my years well. I think it’s very special to feel that way, especially as a woman in America, where youth is over-valued in this completely insane way. At this point, I don’t need thank-yous or awards; I just hope that some people will buy my new book, What If We Get It Right?, and, more importantly, actually read it. I really hope this book gets read.

Just so you know, I procrastinated writing it for two years because my ego was just not big enough to write the book that I envisioned. My knowledge is not vast enough. This is a dissertation project. This is five years of reading everything and trying to synthesize it. So it became an anthology of sorts, of 20+ interviews. The anthology is a format I’ve continuously gravitated towards. And, besides, who am I to answer the question I pose in the title? So instead of trying to become conversant in all the areas of expertise that are required for creating visions of climate futures, why don’t I just talk to my expert friends? I cajoled people into sitting down with me for interviews just like this one. And I got to ask them, “What does getting it right look like to you? Describe it. What are the hurdles? What are the boring, practical, unsexy things that we need to get out of the way to unlock this future?”

I’ve had the chance to have these deep, existential conversations with Hollywood producers and filmmakers; youth climate leaders; architects and landscape designers; farmers and foresters; policymakers and lawyers; community organizers and activists. And instead of me paraphrasing and quoting, you can hear it from them directly. The text is two-thirds transcribed, heavily abridged interviews, alongside essays by me and also poetry, quotes, and art. And I’m about to get very involved in its actual physical design because not only is climate change a collective action problem, it’s a collective understanding problem.

Mark:

I can’t wait to read this anthology of passionate voices, but I’d like to pause for a second and acknowledge something that’s been on my mind. I recently learned the value of naming things out loud that are important to me in real time to honor ideas or people. And I wanted to say that we recognize that what you do is not easy. You bear the burden not only of your own usefulness, but of being in the service of the rest of us finding our paths of usefulness. So I’m just naming that. And giving you your flowers. That service is appreciated.

“If people need a pep talk in order to find their role—if they need to be reminded of the stakes, the opportunity within those stakes, and the possibility and the necessity of this moment—then I’m here for that.”

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson’s anthology of writings by 60 women at the forefront of the climate movement, published in 2020.

Ayana:

Thank you. So my mom was a high school English teacher. She was the breadwinner for our family of three. I went to private school my whole life on scholarships and I got to do all the extracurricular activities and everything I could ever have dreamed of. We didn’t travel very much at all, but I grew up in New York City, so I had the Met and Fort Greene Park. I essentially had an upper middle-class childhood despite having a working-class family. My parents were very clear that with that privilege came a duty to give back. A duty of service. It wasn’t necessarily a constraint, but it was a directive.

I don’t feel any of this is a burden. I’ve had so many opportunities, and what has unfolded is partially what I have chosen, and partially what I’ve realized to be the confluence of what I’m good at, what needs doing, and what I enjoy doing—this climate action Venn diagram concept that I developed. I find it hilarious that people call on me to do motivational speaking based on that, as someone who, as I said before, is avowedly not an optimist. But if people need a pep talk in order to find their role—if they need to be reminded of the stakes, the opportunity within those stakes, and the possibility and the necessity of this moment—then I’m here for that.

Mark:

Reminding people what’s at stake and what is possible in this moment is critical. How much of that reminder, do you think, includes confronting some of the harder truths about why the climate movement has struggled to be more inclusive or struggled to build momentum and motivate more people to act?

Ayana:

After George Floyd was murdered and we experienced this wave of activism around Black Lives Matter, I found myself in a very unexpected position because the climate movement, and the environmental justice movement more broadly, needed to reckon with its racism and bias, and with having been so unwelcoming and counterproductively exclusive for so many decades.

Through my rage and my tears, I managed to write some things—with the help of very good editors to filter through the emotions and get to the core of it all—that resonated with people. I found myself, on the heels of launching a book and a podcast in 2020, to be someone who was being called upon. I was getting all of these press inquiries. My public profile went, within a few months, from a few thousand Instagram followers to 100,000. Suddenly people were calling me an influencer. I’m like… all this because I wrote one viral op-ed about how we can’t solve the climate crisis without Black people—which to me seems just very obvious.

Mark:

Super obvious.

Ayana:

It’s like putting a hole inside of a fish trap.

Mark:

Yeah.

Ayana:

The climate crisis is a big fucking problem. Of course you need us. But still, it was very strange for me. I realized that all these media outlets weren’t calling to be nice. They were calling because they needed someone who they felt could connect the dots in a way that would be understood and received. So as much as I was burnt out by everything, I also knew that, if this is the moment when people are ready to listen, then this is the moment when I have to speak.

I never aspired to become a public figure. It’s funny, too, because all of this transpired while I was sequestered at my mother’s farm during the Covid lockdown, so it was all, physically at least, at arm’s length. Then we reemerge and I’m getting recognized at the farmer’s market. I’m like, “Wait, what happened? I’m just getting some kale. Everybody chill.” But I do feel like I have found my role. We are each, in our own way, made for this moment, and finding the ways in which we fit feels really good.

Mark:

It reminds me of something someone whose content I consumed in abundance prepping for this conversation once said: “Go where there is a need and where your heart can find a home.”

Ayana:

Oh... that was a good one. You got me in my feelings.

Mark:

I’m also fascinated by this idea of home. We are both descendants of the island of Jamaica. When you talk about the idea of finding a home and thinking about what home means to different people, I’m struck by the example of Jamaica—the power and scope of our diaspora and that connective tissue. The island is 146 miles long and home to three million people, with almost as many Jamaicans living abroad. As we start to think about how people define home, and how people understand their place and where they can have the most impact, that will also involve looking at the places that are the most impacted, and looking at where service might actually be the most meaningful. Do you think that this is also an opportunity to connect diasporas, or even to return?

Ayana:

Absolutely, and on several levels. I think a lot of families are asking themselves now: “Where do we want to be? How do we be together?” My mother is moving in with me. Our little family is reconvening. That’s partially where we are in our life cycles, too. I’m seeing this with a lot of my friends. People want to be near their parents, near their children, near their nieces and nephews and siblings. I think about it in the context of climate change and where we’ll be safe. If I’m going to buy property, where is a safe place to buy and make a home? If we are choosing where to live, what is wise? Who do we want to be with when shit hits the fan? Who are our people? More and more people are being deliberate about these decisions. On the flip side, the migration trends within the US are towards the South and the Southwest, which is completely illogical when you think about climate projections—like dangerously illogical—but logical perhaps in terms of community and roots and real estate prices. To me, the question of home is becoming very practical. What does home mean when the world is changing so quickly around us?

My tender heart cries reading the news almost every day because there are so many horrors going on all over the world. I have to limit my dosage of bad news. I don’t ignore it, but at some point taking in more details won’t change what I need to go do. I need to focus most of my energy on contributing to making things better, as opposed to being overwhelmed by all that is wrong.

Mark:

It takes discipline.

Ayana:

My upbringing was very present-focused. It wasn’t about family stories or family history. My parents helped me to navigate the world that we lived in, but my family wasn’t one of archivists and storytellers. My parents were surprised that I became a person who could tell stories because they didn’t model that for me at the dinner table. But I am always grateful to hear stories of the gathering and coalescing of diasporas because that is very much what this moment calls for: a very deliberate re-imagining of home.

Mark:

The deliberate part is important. It won’t happen by accident.

Ayana:

Nothing will.●

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson is a marine biologist, policy expert, writer, and Brooklyn native. She is co-founder of Urban Ocean Lab, a think tank for the future of coastal cities. She co-edited the bestselling climate anthology All We Can Save, co-founded The All We Can Save Project, and co-created the Spotify/Gimlet climate solutions podcast How to Save a Planet. Her writing has been published widely, including in the New York Times, Washington Post, and Scientific American. Dr. Johnson’s new book, What If We Get It Right?: Visions of Climate Futurism, comes out in September 2024.

Mark Chambers is an environmental policy leader, advocate for social justice, and licensed architect inspired by public service and lessons of collective action. He is Vice President of Partnerships at Elemental Excelerator, a nonprofit investor focused on scaling climate technologies with deep community impact. He recently served the Biden White House as Senior Director for Building Emissions and Community Resilience and was previously the Director of Sustainability for both New York City and the District of Columbia, where he led efforts to accelerate climate policy implementation in America’s largest city and the Nation’s capital. Mark lives in Harlem with his wife and two children.