Other Networks: Taeyoon Choi on Infrastructure and Equity on the Decentralized Web

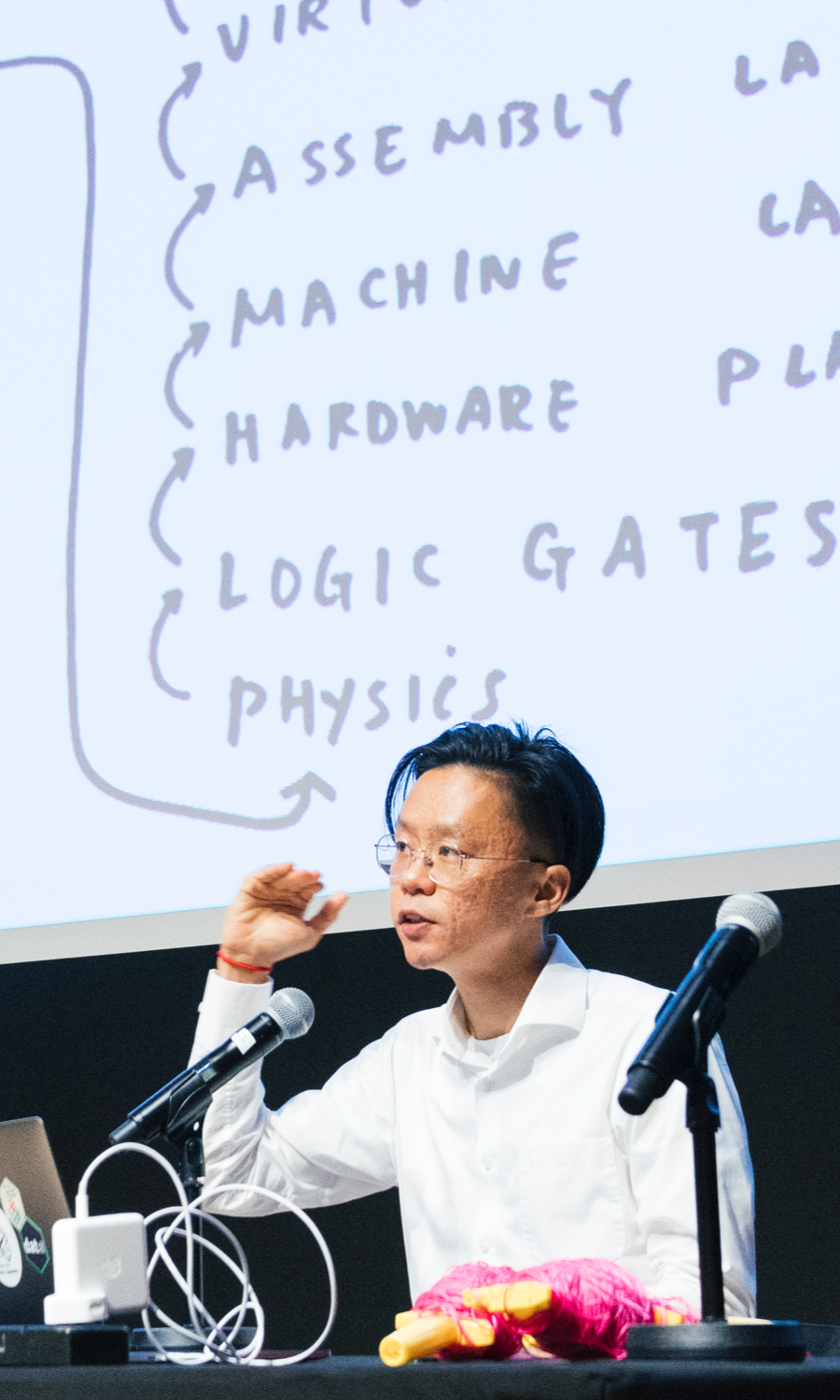

M+ Matters: “Art and Design in the Digital Realm,“ 2018. Courtesy of M+, Hong Kong.

The World Wide Web (www) is an application that runs on top of the Internet. It’s like a giant address book through which you can follow the hyperlink to find information.

Since it was invented in 1989, the World Wide Web has become both the global standard and the building block for tech products and platforms. But its success came with limitations and growing concerns around the centralization of power among the small clusters of giant tech corporations. Decentralized Web (DWeb) technologies are alternatives to the contemporary World Wide Web. The recent development in DWeb technologies focuses on communication protocols (how computers speak to one another) and network infrastructures (where the computers speak to one another) that can enhance privacy and security, allow for decentralized governance, and/or safeguard data on a long-term basis. Experimental DWeb applications include Patchwork, Beaker Browser, and Cabal and popular Dweb protocols include IPFS, Secure Scuttlebutt, and GUN. DWeb technologies are tangentially related to blockchain technologies (which record financial transactions on cryptographic hash) but their intentions and designs are fundamentally different.

Decentralized Web Summit 2018. Photo by Brad Shirakawa. Courtesy of the Internet Archive, San Francisco.

1. Wayback Machine. https://archive.org/web.

2. Decentralized Web Summit 2018: Global Visions. https://www.decentralizedweb.net.

3. Taeyoon Choi’s Distributed Web of Care. https://decentralizedweb.net/distributed-web-of-care.

In the last few years, DWeb technologies have been a hot topic among open-source engineers, academics, policy makers, and investors. I had a variety of unique chances to meet DWeb community members in the San Francisco Bay Area, between 2018-19. Some were good-hearted engineers and grassroots community organizers from the global South who were interested in building a more equitable network. They shared optimism for creating an alternative that would grant access to technology without discrimination based on gender, race, and financial resources. This would also grant more agency to users to determine how their data can be used by corporations and the government. In July 2018, the Internet Archive (a nonprofit organization known for the Wayback Machine [1]), organized the Decentralized Web Summit [2] at the San Francisco Mint. I was invited as an artist to lead a participatory performance called Distributed Web of Care [3]. I coordinated a few hundred attendees to form various types of real-life webs using pink mason line strings. The attendees engaged in playful improvisation over a period of twenty minutes.

Left: M+ Matters: “Art and Design in the Digital Realm,“ 2018. Courtesy of M+, Hong Kong. Right: Decentralized Web Summit 2018. Photo by Brad Shirakawa. Courtesy of the Internet Archive, San Francisco.

During the main events at the Summit, a group of grey-haired white men were introduced as the “Fathers of the Internet.” They were indeed the creators of the original World Wide Web and related technologies. Another group, made up of mostly younger white men, were introduced as the new generation of Internet pioneers. The narrative was structured like a passing of the torch from one generation of white male engineers to a younger one, in front of an also majority white male audience. Aside from their common gender and racial attributes (which are typical of the tech sector), I noticed some of their shared faith in tech-solutionism and, consequently, their dismissal of social and integrated approaches to global issues. To be fair, the DWeb Summit may have been one of the most progressive conferences I’ve attended, with a “diversity & inclusion” policy that resulted in a noticeable presence of women, QTPOC, and non-binary folx. I had a pleasant experience there, and also enjoyed a chance to change my biases. I was suspicious of anything blockchain-adjacent, in a knee-jerk reaction to the cryptocurrency hype of 2015-16. At the DWeb Summit, I met some blockchain engineers, product managers, legal experts, and genuinely interesting people who opened my mind to imagine what could be possible.

Ink drawing for Distributed Web of Care merchandise, 2018. Courtesy of Taeyoon Choi.

4. John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.” Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/cyberspace-independence.

Decentralization is a political concept as much as a technical one. From the beginning, the Internet was a home for counterculture rebels and geeks looking for an alternative space to express themselves and to connect with others alike. “We are creating a world that all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth” [4] wrote John Perry Barlow, lyricist for the Grateful Dead and founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, in 1996. In reality, it has become incredibly clear that the Internet is not a utopia. It reflects the implicit biases, sexism, and racism of the people who created and use it. Everyone was equal on the Internet but some were more equal than others.

On the day after the DWeb Summit, I met a group of engineers and activists at an unofficial post-summit convening at the Omni Commons, a community space in Oakland. It was interesting to reflect on the summit with a group of local and international activists/technologists. Over shared bowls of soup and tacos, we discussed the jarring disconnect between the interior space of the SF Mint—a place the US treasury used to produce and keep coins—where we enjoyed sparkling wines in the fancy boardroom, and the homeless people asking for help right outside. The disparity of wealth and access to technology was visceral. I wrote a poem at the SFO airport, reflecting on my impression of Silicon Valley and the ideals and reality of decentralization.

Distributed Web of Care party, 2018, Ace Hotel New York. Photo by Eva Woolridge. Courtesy of Taeyoon Choi.

“In reality, it has become incredibly clear that the Internet is not a utopia. It reflects the implicit biases, sexism, and racism of the people who created and use it. Everyone was equal on the Internet but some were more equal than others.”

Writing from the land of hexagon stickers, reusable water bottles, and horseshoe theory, far extremes hold striking resemblances. Uncanny juxtapositions in no particular order: Blockchain idealism and melancholic cynicism. Electric bikes and homeless wagons. Alt-right libertarians and solarpunk anarchists. Initial Coin Offering and legalized piracy. Immigrant workers and business travelers. Speculative public infrastructures and private real estates. “The Building is the Computer” by Dynamicland and How To Do Nothing by Jenny Odell. Uber “community” and “what kind of community rates each other with stars?” LinkedIn melodrama and corporate offices with more dogs than Black and Brown people. Men who don’t shut up and men who don’t speak at all. Dolores Huerta and her poster in the Facebook HQ. Counterculture and neoliberalism. The Whole Earth Catalog and Amazon Prime. A world without history—the world as history.

Distributed Web of Care party, 2018, Ace Hotel New York. Photo by Eva Woolridge. Courtesy of Taeyoon Choi.

5. Francis Tseng,“Who Owns the Stars: The Trouble with Urbit.” Distributed Web of Care. http://distributedweb.care/posts/who-owns-the-stars/.

6. Mindy Seu,“Making Space in Online Archives.” Distributed Web of Care. http://distributedweb.care/posts/online-achives/.

7. Shannon Finnegan, “Accessibility Dreams.” Distributed Web of Care. http://distributedweb.care/posts/accessibility-dreams/.

8. Ari Melenciano,“Building a Museum 353 Years in the Future.” Distributed Web of Care. http://distributedweb.care/posts/ari/.

While marinating on the experience, I made an online journal called Distributed Web of Care with a decentralized protocol called Dat (now called Hypercore). I wrote an essay titled “Racial Justice in the Distributed Web” and asked my friends and colleagues to contribute their thoughts about the DWeb. Francis Tseng wrote “Who Owns the Stars: The Trouble with Urbit,” [5] Mindy Seu wrote “Making Space for Online Archives,” [6] Shannon Finnegan wrote “Accessibility Dreams,” [7] and Ari Melenciano wrote “Building a Museum 353 Years in the Future.” [8] The essays explore the future of the web through artistic and/or political imagination. For example, Melenciano explores “the eradication of racial oppression in future times through the speculative design and futuristic ideating of a utopian city and society called Afrotopolis.” She offers an opportunity to imagine a different kind of web that centers racial justice.

9. DWeb Principles. https://getdweb.net/principles/.

The Internet is literally a network of computers speaking to other computers. The World Wide Web is the de facto information retrieval service of the Internet. The DWeb is an opportunity to build different types of protocols between networks and devices, but DWeb technologies on their own are not inherently more equitable than other technologies. We are in the early stage of DWeb and we can still shape its future. The DWeb Principles, created by some of the participants of the DWeb Summit, set “human agency, distributed benefits, mutual respect, humanity, and ecological awareness” as top priorities. [9] As new DWeb technologies become more common in the next few years, now is the time to have a conversation between technical and non-technical community members to co-create codes of conduct and that weigh racial, gender, and environmental justice as equally important elements of future technology. These explorations of technology and society may also open up space for artistic expression, cultural connection, and community relations that are also more caring.●

M+ Matters: “Art and Design in the Digital Realm,“ 2018. Courtesy of M+, Hong Kong.

Taeyoon Choi is an artist and educator who works with drawing, painting, computer programming, performance art, and video. He explores the poetics of science, technology, society, and human relations, believes in the intersectionalities of art, activism, and education, and supports disability justice, environmental justice, and anti-racism. As a co-founder of the School for Poetic Computation in New York City, Choi helped build its curriculum and administration. He is currently based in Seoul, South Korea.