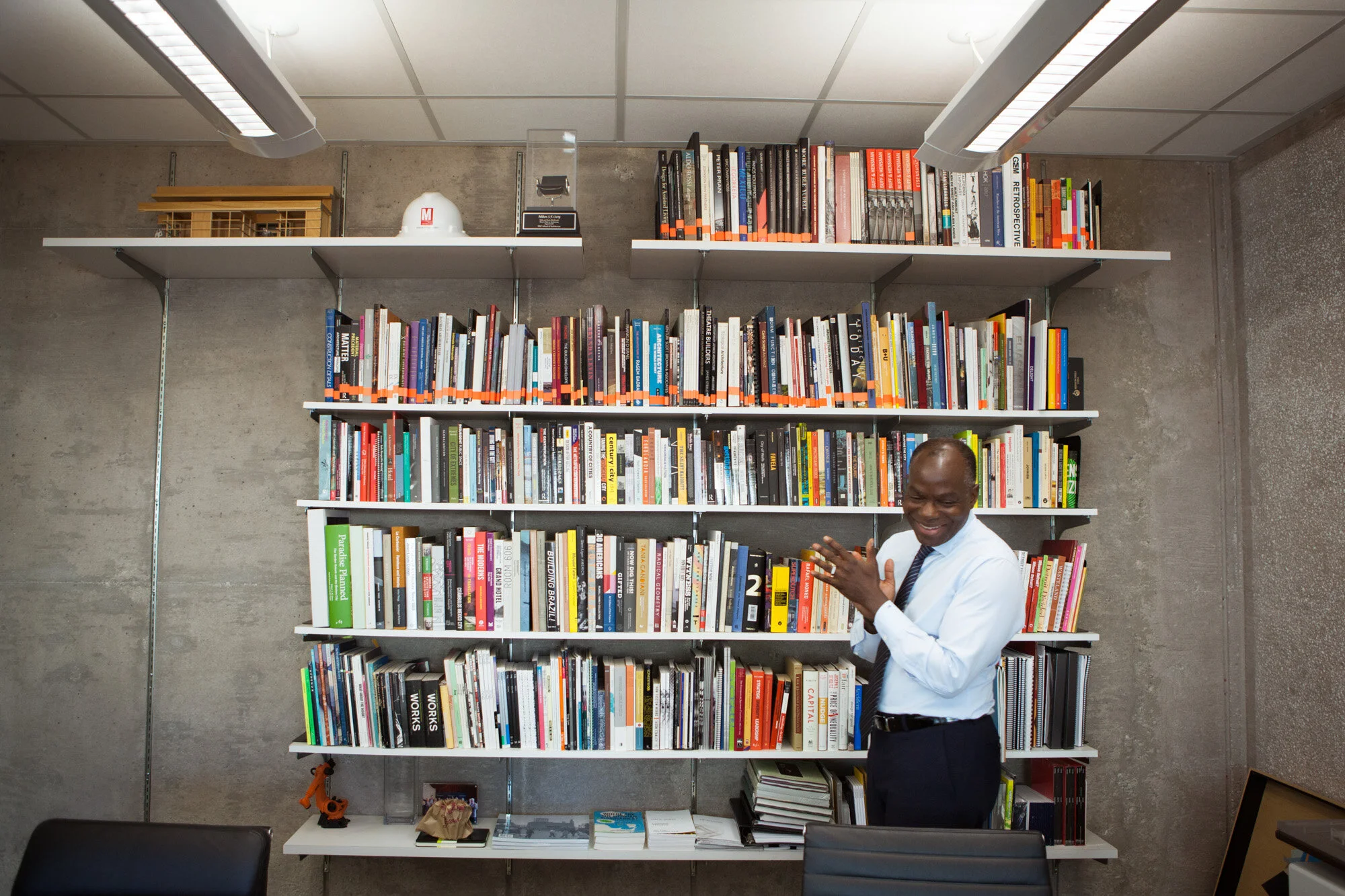

Milton Curry, Dean of the School of Architecture at USC, speaks with Deem’s founders about the meaning of social practice

Photography by Sara Pooley

What does social practice mean to you?

Social practice means practicing an ethic of connection and practicing an ethic of compassion. I think it begins there. When you move into the range of work being done under the rubric of social practice, for me it means being true to certain principles but also to theoretical and ideological commitments in terms of how certain spaces, certain people, and certain identities are represented. How do we do that and what tools do we use. As designers, we work with a variety of tools—text, images, space, three-dimensionality, conceptual frameworks.

How does social practice fit into your work as an educator and a curator?

First and foremost, going back to the notion of connection, my social practice is about connecting students and connecting faculty to the broad constituencies that architecture touches. That may sound intuitive but the reality is that we've been disconnected from so many communities—underserved communities, low-income communities, communities of color. The practice and the academy have been extremely disconnected from many of these communities for generations, so it's wonderful to see the term “social practice” become more mainstream. But this doesn't negate that there's a lot of work to be done in building trust and in building the conceptual, theoretical, and ideological frameworks to allow us to address those communities with dignity.

“…the reality is that we've been disconnected from so many communities—underserved communities, low-income communities, communities of color.”

How would you define or describe the realm of the social and the ecosystem of actors within a social practice?

The notion of the social comes from a philosophical point of view—for example, philosopher Georg Hegel, who looks at how becoming a part of society and a part of the political are what move individuals into the realm of the social. But there are also different perspectives, like that of Miranda Fricker and Kristy Dotson, who think about the epistemic qualities that we all share as humans and how our epistemic reality is in fact very fragile.

“We're in a phase where we're developing new terms almost every five minutes and there’s a feature of our neoliberal reality in which terms tend to become commodities.”

For example, by engaging in thoughts or actions that are dismissive of other people, we actually interrupt the part of our psychological continuity that connects us to other human beings. I think it’s important to philosophically disrupt some of the ways that we relate to one another, even things that have become universal, and return to the idea that in order to be epistemically full humans, we need to have empathy and compassion. Anything less distracts from our ability to be fully human.

As we’ve brought Deem into the world, we’ve noticed that the idea of “social practice” can be very opaque and mysterious to people. Why do you think this idea might be perceived this way?

I think that we're in a phase where we're developing new terms almost every five minutes and there’s a feature of our neoliberal reality in which terms tend to become commodities. So, “social practice” on the one hand brands the activity within academia yet remains an opaque concept to the general public, while a term like “social justice” has great resonance within the general public yet remains quite generic when subjected to academic critique. Perhaps linking these two terms would produce clarity within both the research community and the public.

“When you look at something like planetary warming, there's no amount of money that's going to save you from a planet that’s failing. Even in the cloud of political and social upheavals that we're going through, I think there is clarity in the fact that social engagement is a part of succeeding as a business.”

How do you see social practice translating to the world of design?

From an architecture standpoint and from an educator standpoint, I think urban planning has occupied a lot of this territory in the past, in terms of community engagement. For a long period of time that engagement was assigned to the planner or city government, whereas now I see undaunted millennials believing that, whatever their background, they can have an impact. I also see a younger group of designers and architects using the core of their practice as the engine to deliver services to communities that were previously underserved or overlooked by architects.

The way social practice can be used today is much more liberating than the template for community engagement that urban planners gave to architects, developers, and designers. The difference takes the form of new ways of dealing with and connecting with communities. This means going in as partners; creating a knowledge exchange; realizing that the people have certain expertise that you don't. Instead of coming in as the architect on that high horse, coming in as a fellow citizen who is trying to creatively utilize expertise to think about ideas alongside people who may have very different experiences and points of view.

Why do you think there's a pedagogical shift in the U.S. towards social engagement practices?

I think a lot of it is economic because diversity and issues of social impact are now good for business. You see these conversations in the headlines of newspapers and business sections. Even the CEOs of major corporations claim no longer to be operating the companies just for shareholder value; now there are other values at play. I think that's part of a perceptual shift towards the reality that we're all in this together. When you look at something like planetary warming, there's no amount of money that's going to save you from a planet that’s failing. Even in the cloud of political and social upheavals that we're going through, I think there is clarity in the fact that social engagement is a part of succeeding as a business. I think that can be positive, as long as it isn’t used to exploit.

“The way social practice can be used today is much more liberating than the template for community engagement that urban planners gave to architects, developers, and designers.”

— Milton Curry

What role does publishing play in your work?

Like your publication, which will have a life both online and in print, I think there are really important platforms for engaging broad constituencies. When I started my first academic journal during my time at Harvard, there were very few journals of architecture. Most that did exist were focused on pedagogical issues such as teaching and student work. It wasn’t until the mid 80s and early 90s that journals emerged with a focus on issues that related to architecture within the realms of history and theory.

The world has changed since then, of course, and now podcasts, online venues, and print platforms can engage different publics. I think we've seen this more in the art world than the architecture world, but I think we're beginning to see it also in design because designers can create platforms in creative ways that begin to imbricate a larger polity.

“I don't think you can have an engaged, successful, meaningful practice that's disengaged from theoretical thinking. But I also don't think that you can be a successful theoretical thinker without engaging in the real world.”

Each publication that I’ve been involved in has been a different journey, a different focus, and a different audience. When I started Appendx in 1993 , with two other editors at Harvard, it was around bringing social, race, and gender issues into the discourse of architecture theory. When I started CriticalProductive in 2008, we were bringing questions of urbanism and urban design into focus and trying to shape the debate around how we think about cities (particularly in Latin America and the United States) in terms of exclusion and inequity. Mixing history, theory, and design has always been interesting to me. That's really been the driving force behind being involved in publishing.

What do you think is your value in terms of your approach to curating and facilitating architecture and design conversations in Los Angeles in 2019? Let’s talk about this time and this space.

As you might know, USC has a great history both in Southern California and across the globe. The Case Studies House Program, which explored alternatives to conventional suburban residential development—was ideated here at USC Architecture with deans, former deans, professors, faculty, and students. There’s a great tradition of group research at this school. There's also a tradition of eclectic individual thinkers who never do the same thing twice—graduates of ours like Frank Gehry, Thom Mayne, and Paul Revere Williams. I think those two elements continue to be the driving force of the school pedagogy: the eclectic, engaged, capacious thinker and maker alongside group-level research and collaboration that really move the ball forward on particular issues of the day.

I associate our school with three ideas: optimism, experimentation, and social consciousness. Through these three prisms, our students and faculty move fluidly between theory and practice. I don't think you can have an engaged, successful, meaningful practice that's disengaged from theoretical thinking. But I also don't think that you can be a successful theoretical thinker without engaging in the real world, whether that means practicing architecture, some form of design, or just getting out and understanding what's happening on the ground. And though we have a lot of reasons to be pessimistic (and certainly this was true at other points in history), I think optimism is crucial to being creative and experimental and able to think outside the box.

What are your methods for engaging students and the public to construct their own views on and relationships to design and architecture?

Exposure. It's the same thing you would do with your child. You expose them to a variety of things and then let them decide what they're interested. We're a big school; we have a pluralistic view of the world because we have a lot of voices in play. But I hope that we can avoid producing the kinds of pedagogical dogmas that I experienced when I was in school. The combination of rigor and dogma can lead to very homogenous design projects. At USC, I see rigor as being separate from dogma, which is good because although I am very interested in rigor, I have no interest in dogma. I have an interest in our students and faculty taking positions, backing those positions up with dialogue, and then letting the chips fall where they may. In our lecture series and in our conversations, we're telegraphing interests and topics that we think are contemporary, but what each person takes away is ultimately their own decision.

Five words to describe social practice that come to you naturally?

Engagement, empathy, compassion, ethics, and creativity.

You can find the calendar for USC School of Architecture’s forthcoming public programming here.