Placemaking When “Freedom is a Place”: Tracing Liberatory Infrastructures from Queer Riis Beach

Text by Jah Elyse Sayers

Illustrations by Acacia Rodriguez

Illustration by Acacia Rodriguez

In 2018, I began intentionally gathering stories of Bay 1 of People’s Beach at Jacob Riis Park in Neponsit, Queens, New York City.

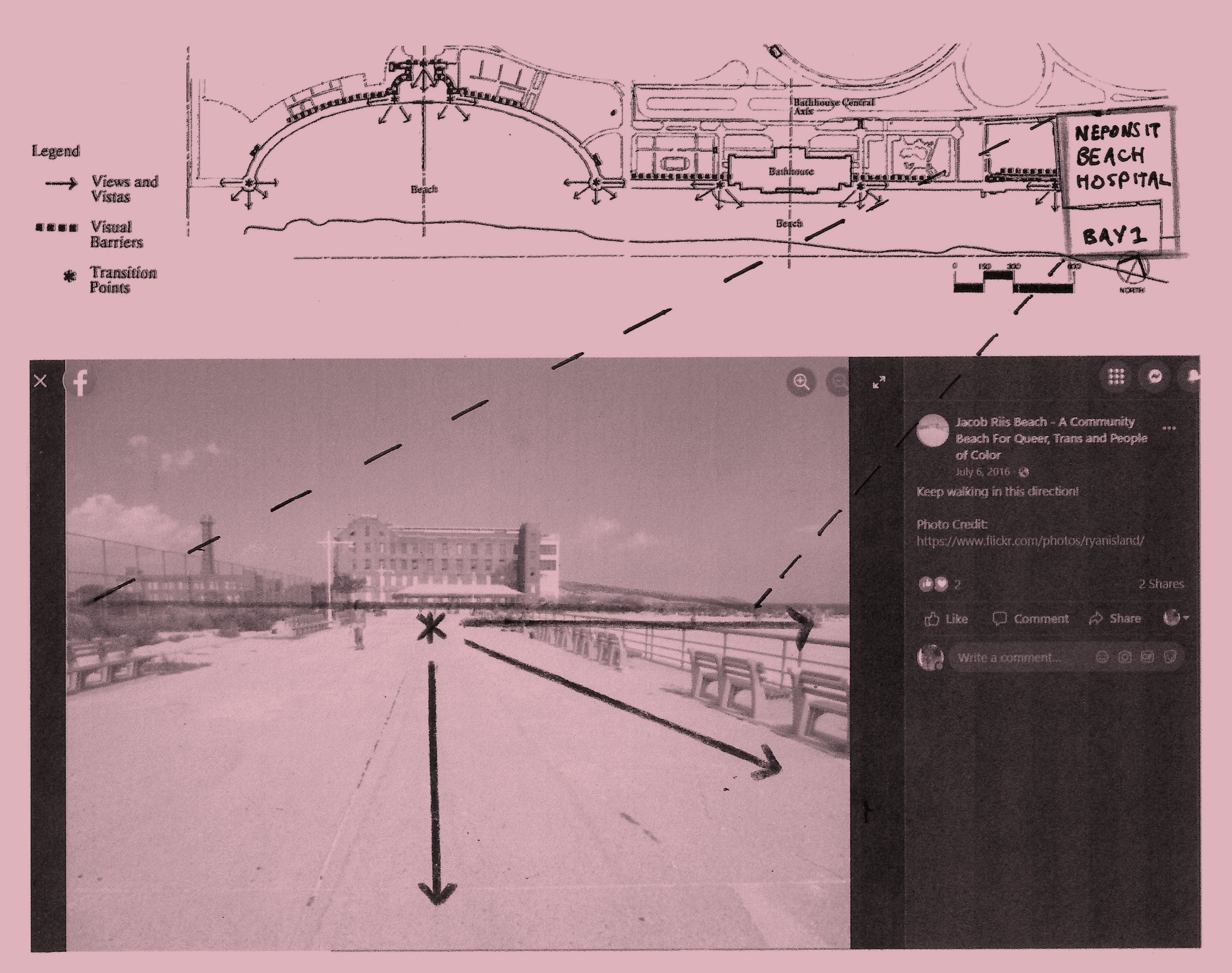

The area is generally referred to as “Riis” and has served as a queer gathering place since at least the 1940s, facilitated by the beach’s proximity to Neponsit Beach Hospital. The hospital’s buildings provide a sense of cover to the beach by blocking sightlines from the boardwalk, bus stop, and sidewalk. The hospital buildings, however, face demolition.[1] The sense of safety they provide is at risk of displacement.

As I conduct surveys and interviews, comb archives, participate in community organizing, and share conversations, I notice that Black queer and other queer-of-color stories that begin with or move through Riis often travel elsewhere. They challenge the idea that the place in placemaking might be limited to urban public and shared spaces like blocks, parks, gardens. They move me toward Katherine McKittrick’s assertion that “stories make place” and Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s assertion that “freedom is a place” to reflect on storytelling as placemaking and placemaking as, potentially, freedom-making.[2] Black queer storytelling’s insistence on embodied mobility demands method-making that seeks threads between seemingly disconnected time-spaces and ephemeral experiences of freedom and safety. These threads potentially trace out existing alternatives to racial capitalism’s illusions of inevitability, against and beyond reliance on private property.[3] I am specifically interested in how Black queer and trans people, as well as other queer and trans people of color, draw these connecting lines and, through this, choose and make liberatory ecosystems that offer possibilities of belonging that defy ownership and its racialized and gendered constructions of significance.[4] Can we recognize blocks, parks, and gardens as infrastructure for making a larger place: freedom?

Adapted from pages 4-8 and 4-9 of Lane, Frenchman and Associates, “Jacob Riis Park: Cultural Landscape Report,” 1992.; Screenshot of “Jacob Riis Beach - A Community Beach for Queer, Trans and People of Color,” Facebook.; Annotations by author. Notice the Facebook profile photo is not of the beach itself and is instead of one of the hospital buildings marking the end of the boardwalk. The elevated seawall, fencing, and building obscure views of Bay 1’s beach. This choice of photo for the page embraces and helps beachgoers navigate obstructions of visibility.

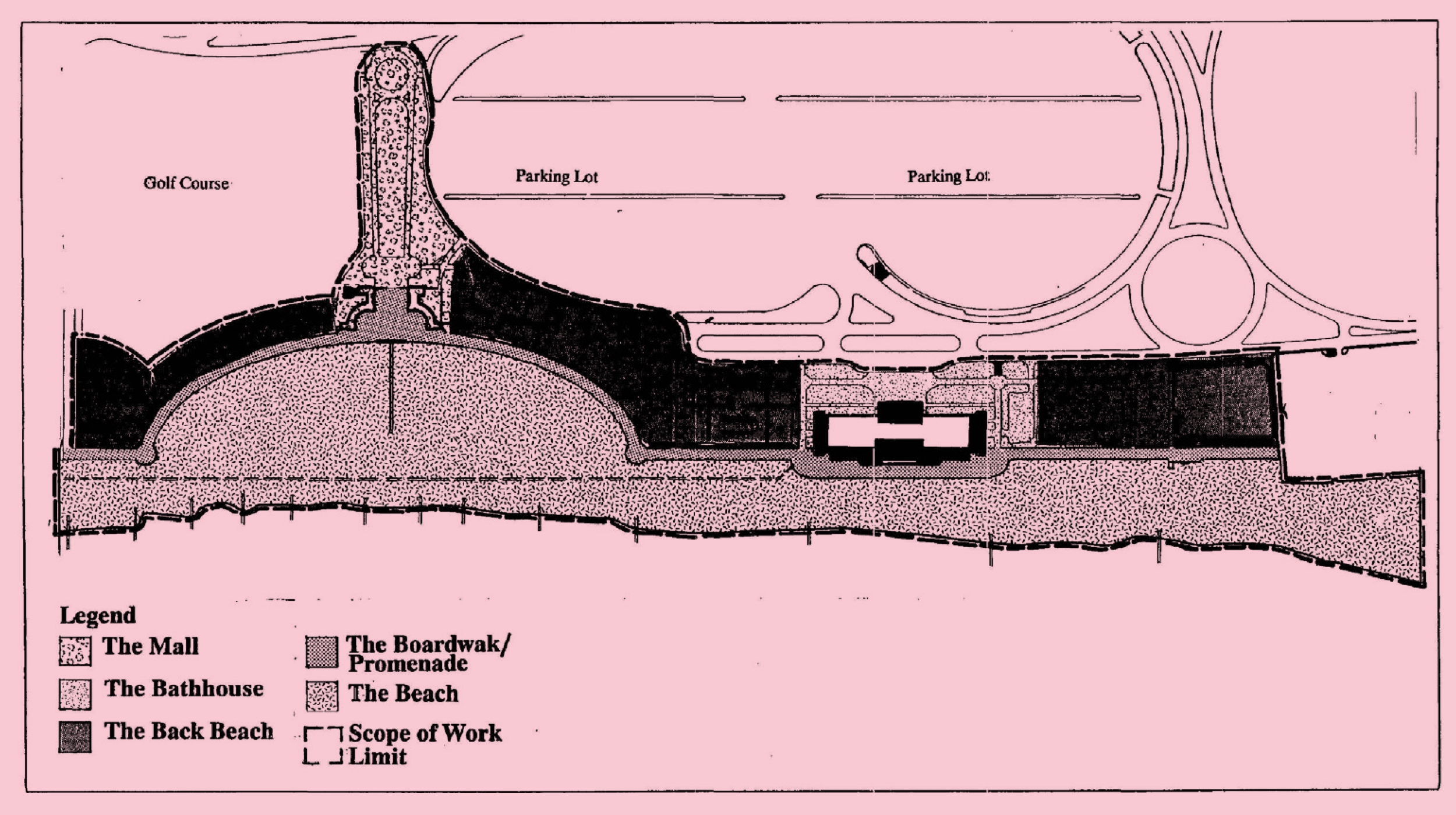

On paper, a story about significance appears to protect Jacob Riis Park via the Jacob Riis Park Historic District. However, preservation extends only to “historically significant” features. Despite the beach’s role as a refuge for queer placemaking, the National Park Service defines significance within a tight spatiotemporal context.[5] The period of significance here is confined to 1932-37 (related to Works Progress Administration [WPA] construction of Art Deco architectural styles). Spatial significance is confined within the “scope of work/limit” demarcated below by a thick (but porous) line:

From p. 1–6 of Lane, Frenchman and Associates (1992)

In Black queer and trans storytelling about Riis, the porosity of the scope of significance is undeniable. Audre Lorde writes about 1950s Riis in Zami, but she does not discuss her time at the beach beyond “split[ting…] early.” Instead, she writes of its traces sticking to her skin far beyond the beach’s boundaries. Long after the ocean water dried from their bodies, Lorde and her partner were “full of sun and sand,” and they “loved with the salt still on [their] skins.” She writes that her time at the beach graced her with a certain “raunchy(ness) and restless(ness),” how she knew—more consciously and pridefully now than before—that she was “fat and Black and very fine,” and later challenged an expression of anti-Blackness that she would typically “let[…] go.”[6] Her experience of Riis followed her well beyond park boundaries to impact the ways she moved.

But despite Neponsit Beach Hospital’s shared history of elements of WPA-funded 1932-37 construction and Art Deco architecture, the hospital is outside the historic district’s spatial limit, and documented queer use of the beach falls outside the period’s temporal limit, rendering both queer use of Bay 1 and the buildings that provide its visual cover beyond the scope of worthiness for preservation.

Similar ruptures animate contemporary tellings of Riis as I hear stories about last night’s parties, at-home preparations, subway transfers and bus rides, bodega and chicken-spot stops, musings about neighboring residents and the Black trans*Atlantic, tales of stubborn sand in apartment floors and bedsheets. Beachgoers often mention the hospital as a landmark and protective feature, and I’m sometimes gifted a popular, though grim, fiction of the hospital’s history: that it was a psychiatric facility where queer and trans people were tortured.

In reality, Neponsit Beach Hospital initially opened in 1915, following advocacy by the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor as a beachfront tuberculosis sanitorium for children.[7] Riis was initially part of the hospital grounds in order to offer patients the “fresh air cure.”[8]

“Neponsit Beach Hospital for Convalescent Tubercular Children. Children on beach in front of 4-story building with wings.” Department of Health, Accessed from NYC Department of Records & Information Services, Collection: “DPC: Public charities & hospitals.”

Vulnerable to shifts in the military industrial complex, Neponsit Beach Hospital underwent multiple closures during the 1940s. Changes in tuberculosis treatment protocols and a land-use dispute between City Planning Commissioner Robert Moses and the city comptroller led to another closure in 1956 until 1961, when the hospital reopened as a nursing home and its beachfront was reallocated to park grounds. Queers filled the gaps, both through cuts in chain link fences and in years between court decisions, taking advantage of the buildings’ concrete disruption of policing gazes. I suspect that the fiction of an anti-queer psychiatric facility originates in the occasional application of the term sanatorium to describe psychiatric institutions.[9] Rather than focus on this erosion of public memory, we can locate an impulse toward connection across an otherwise divisive property line and preservation boundary, as most of these imaginings place historical beachgoers in conversation and solidarity with patients. As fleeting pleasures in the 1940s accumulated into a consistent presence on the beach by the mid-1950s, it is more feasible that it was nursing-home residents—from which queer-assumed HIV/AIDS patients were explicitly excluded—that beachgoers interacted with across jurisdictional lines.[10]

The imagined and actual connections between sites is a potentially liberatory thread worth reinforcing through the hospital’s story of abandonment. Around two in the morning on September 11, 1998, then-mayor Rudy Giuliani ordered the nearly three hundred residents of Neponsit Beach Hospital to be transferred to other NYC public hospitals. Given no prior notice, residents were promised they would return pending renovations. Renovations never came, and the residents never returned. The abandonment of patients’ safety was handled out of court, with the city giving patients or their estates settlements of $18,000 each and agreeing to provide advance notice before future mass patient transfers.

Although an assessment in the year 2000 estimated hospital repairs at about $600,000, millions of dollars have been spent since to maintain the hospital buildings’ abandonment through fines for mismanagement, contracting of security personnel, maintenance of security infrastructure such as fences and a guardhouse, piecemeal repairs, and clean-up of debris; another $5 million is marked for demolition.[11] In the wake of governmental neglect of patients and property—what we might call organized abandonment, or governance by neglect[12]—queers have maintained the buildings’ utility from a distance by utilizing their sightline-blocking functions toward safety.

Illustration by Acacia Rodriguez

As demolition looms, can we model the rupturing of an edge after the embodied mobilities of Black queer life and storytelling? In their reliance on and deferral to property logics, dominant systems for allegedly protecting and preserving place(s) or placemaking fail to acknowledge placemaking as living. They instead render some lives (and the socialities amongst them) surplus and appropriate for abandonment and displacement. They render lives unworthy of preservation. We need to embrace approaches to preservation that disrupt rigid divides and risk change by nurturing life itself in order to enable continued placemaking. The organization Gays and Lesbians Living in a Transgender Society (GLITS) proposes a community land trust on the Neponsit Hospital site dedicated to providing trans-centering holistic healthcare with Black trans leadership. Even in its navigation of property systems, this proposed intervention has the potential to loosen the stranglehold of private property logics on public-space preservation by supporting the embodied health of beachgoers. This approach takes seriously the necessity of living to placemaking and the necessity of care to living. It embraces Riis as a crucial site for making life and freedom, at and beyond the shoreline.

“In their reliance on and deferral to property logics, dominant systems for allegedly protecting and preserving place(s) or placemaking fail to acknowledge placemaking as living. They instead render some lives (and the socialities amongst them) surplus and appropriate for abandonment and displacement. They render lives unworthy of preservation.”

No one saw a crucial site of Black queer gathering emerging from a tuberculosis hospital for children. However, a commitment to life means risk, surprise and, to follow Barbara Christian, “tuned sensitivity to that which is alive and therefore cannot be known until it is known.”13 This means reaching beyond scopes spatially, as occurs in the acknowledgement of Neponsit Hospital’s impacts and in the ways beachgoers’ stories of bus rides and bedrooms might carry us to consider public transit accessibility and tenant organizing as preservation methods. It means, too, reaching beyond temporal scopes by expanding the 1930s period of significance not only into the queer gathering of the 1940s and subsequent decades, but also toward our futures. We can build up the infrastructures and nourish the ecosystems of the freedom ephemerally emplaced at Riis if only we support our living all over.●

jah elyse sayers (they/them) works through research, writing, farming, building, teaching, organizing, and art-making to further Black queer and trans liberatory placemaking. jah is currently a PhD candidate in environmental psychology at The Graduate Center, CUNY. Their writing has appeared in Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies and BRICLab Essays; they have performed at Brooklyn Arts Exchange (BAX) and exhibited sculptural work at metaDEN. jah is grateful to Diane Enobabor and Simone Lee Sobers for shaping this article with their listening, reading, questions, encouragement, and thorough generosity.

1. “Neponsit Home Set For Wrecking Ball,” Rockaway Times, February 11,2021, https://rockawaytimes.com/index.php/columns/7443-neponsit-home-set-for-wrecking-ball

2. Katherine McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories (Durham and London; Duke University Press, 2020), 9; Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Abolition Geography and the Problem of Innocence,” in Futures of Black Radicalism (London; New York: Verso, 2017), 227.

3. Informed by the concept of countertopography; see: Cindi Katz, “Accumulation, Excess, Childhood: Toward a Countertopography of Risk and Waste,” Doc. Anal. Geogr. 57, no. 1 (2011): 47–60.

4. see: Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2018); Sara Clarke Kaplan, The Black Reproductive: Unfree Labor and Insurgent Motherhood (Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press, 2021).

5. The National Park Service hosts the National Register of Historic Places and is manager of Jacob Riis Park.

6. Audre Lorde, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 1982), 222–23.

7. The AICP was led by Jacob Riis. The park was posthumously named after Riis.

8. Before the 1940s introduction of antibiotics to treat tuberculosis, open air was the leading treatment for the disease, but traveling to and staying in the resort-like sanitoria built most often in mountainous western states was costly. AICP advocated for a tuberculosis treatment facility that might offer fresh air to city dwellers; see: “$250,000 Raised by a Sick Boy’s Smile,” New York Times, May 2, 1909.

9.“See: sanatorium,” in APA Dictionary of Psychology (American Psychological Association, 2022), https://dictionary.apa.org/.sana

10. Lew Simon, “Lew Fights Back,” The Wave, November 25, 2000, https://www.rockawave.com/articles/lew-fights-back/; James Colgrove, Epidemic City: The Politics of Public Health in New York (Russell Sage Foundation, 2011).

11. Brendan Brosh, “Abandoned Neponsit Health Center Fixed,” NY Daily News, April 21, 2008. https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/queens/abandoned-neponsit-health-center-fixed-article-1.280481; Katie McFadden, “Neponsit Money Pit - The Wave,” The Wave, March 7, 2014, https://www.rockawave.com/articles/neponsit-money-pit/; “Neponsit Home Set For Wrecking Ball.”

12. Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Organized Abandonment and Organized Violence: Devolution and the Police” (The Humanities Institute at UCSC, November 9, 2015), https://vimeo.com/146450686.

13. Barbara Christian, “The Race for Theory,” Cultural Critique no. 6, Spring 1987: 358.