On Digital Gardens: Tending to Our Collective Multiplicity

By Annika Hansteen-Izora

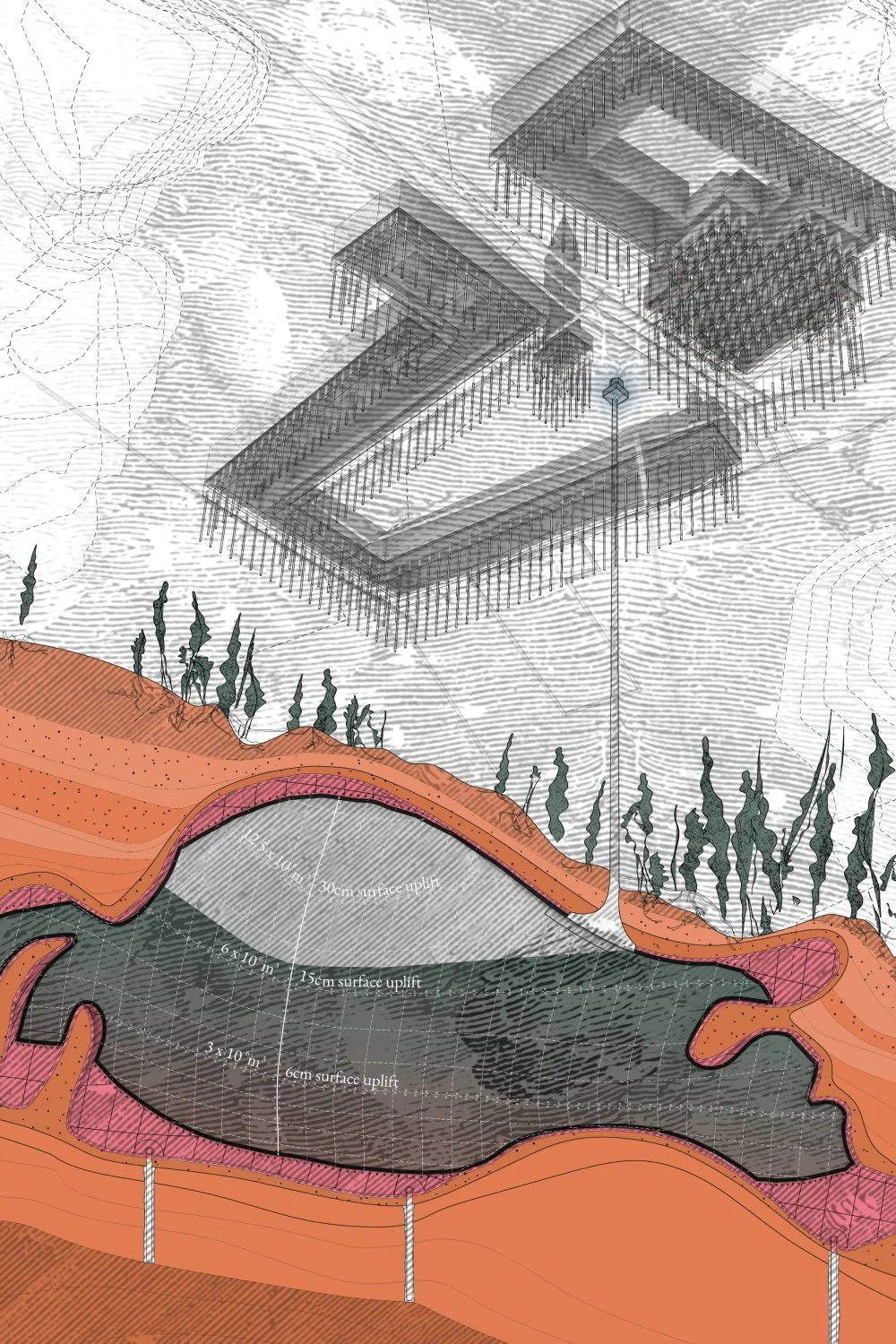

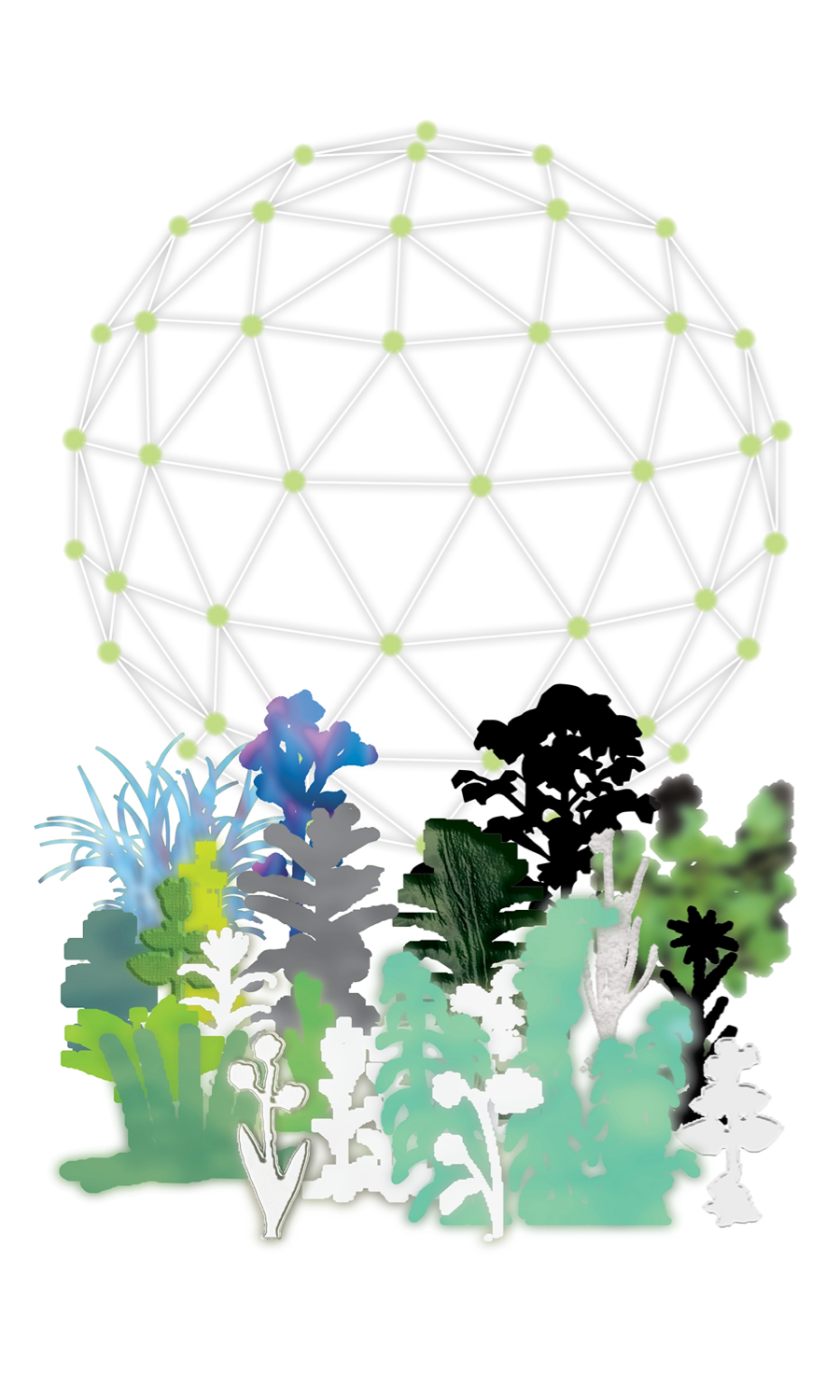

Illustrations by Jun Lin

“Guided by my heritage of a love of beauty and a respect for strength—in search of my mother’s garden, I found my own.”

—Alice Walker, In Search of our Mothers’ Gardens, 1967

“How do you take a walk with someone on the internet?”

—Internet Walks

I grew up in two locations: gardens and the internet. In both spaces, I’m learning what it means to tend to my individual and our collective dreams. My family has a lineage of gardening and techno-exploration, going as far back (in cataloged archive at least) as the garden my great-great-grandmother rooted in her 1920s Oakland home. I grew up tending both the tomato plants in our backyard and my digital art pieces in Kid Pix, later turning to online worlds like Neopets and my on-keyboard safe space of Tumblr. As a kid, gardens and the internet both offered a place to dream, create, and play.

But that was then. Today, the internet is an omnipresent force that organizes the ways we learn, connect, and love—often in ways that are more nefarious than virtuous. The internet is a place, and that place has largely been led by those who value the accumulation of capital over its users’ access to safety, connection, or care.

Nature and technology are often only associated as the other’s antithesis. Nature is alive, fluid, complex. Technology is machine, predictable, streamlined. The social media idiom “go touch some grass” encourages users to leave the internet for nature, the former supplying illusion and the latter providing truth. I don’t disagree with this spectrum. Today, the imagination behind the internet is dominantly shaped by militarization, consumerism, and surveillance. Given the options, I understand the desire to log off and dream in greener places.

But perhaps the separatism between technology and the principles of nature is part of what led us towards this techno-doom reality. I’d offer that the space between digital worlds and nature is one we should linger in. Brand and product designer Frank Chimero noted in a 2018 talk at the Substans Conference in Bergen, Norway, that “if we’re setting out to change the character of technology in our lives, we’d be wise to learn from the character of places.”*

What can the design of online worlds learn from the location of nature? What possibilities are lingering in the seeds of the digital garden?

Digital gardens have largely been understood as websites that allow users to explore and publish thoughts in more fluid and unpolished ways. The term “digital garden” is not new. It’s been shaped by almost two decades of pondering, from early tinkerings in Mark Bernstein’s 1998 essay “Hypertext Gardens” to Mike Caulfield’s 2015 talk “The Garden and the Stream,” which is credited with the term’s first solid definition. Where so many of our feeds are designed around linear time, all major social networks and blogs follow a reverse chronological order, and everything we post is under pressure to be a perfected piece, digital gardens embrace the weird. Many have explored creating digital gardens through sections on personal websites that are dedicated to in-progress and non-linear ideas. My own blog has a digital garden: a page that is specifically for concepts I’m slowly mulling over without alignment to a particular goal or timeline. This behavior is succinctly described in Paul Ford’s 2016 article “Reboot the World”: “Everyone tends [their] own little epistemological garden, growing ideas from seed and sharing them with anyone who comes by.”*

These explorations have been critical for maintaining online spaces that embrace cyclical and ever-shifting thinking. In a techno-social world that is dominantly organized by the pressures of linear feeds, we need digital spaces and frameworks that celebrate the ideas that are seeds just as much as the fully formed blooms.

At the same time, as I wander the internet, I wonder where the digital gardens are that will connect me to fellow gardeners more deeply. More often than not, the digital gardens of today are botanic—privately owned online spaces made for visitors to fawn over while a “do not touch” sign looms in view. These private gardens are generative for our personal learning, but they are far from the communal gardens I grew up in that valued collective work and knowledge. Where are the digital gardens that lead us towards collective learning, play, and dreaming?

To that end, alongside many in the design sphere who are imagining digital worlds rooted in deeper learning, justice, and care, I offer my own fluid, ever-shifting definition of digital gardens.

“Today, the imagination behind the internet is dominantly shaped by militarization, consumerism, and surveillance. Given the options, I understand the desire to log off and dream in greener places.”

A digital garden is a framework for speculation around how online space can be designed from the imagination of gardens. Here, the values of gardens, pluralism, interdependence, sustainability, adaptation, and discovery are centered in the design process of technosocial spaces. A garden is made up of the following parts:

Seeds: the content contributed by gardeners,

such as text, photos, video, audio, or other digital media.

Gardeners: the users that invest in tending to and growing the garden.

Soil: the framework, meaning the design system and processes the garden is rooted in.

Elements for growth (such as water, sunlight, and the wellbeing of the gardeners): the design values that guide that garden.

Below are eight values that have guided my own understanding. (Note: this is by no means a complete list; any gardener knows that the lessons gardens offer are endless. Look at this as a collection of beginning seedlings, and an offering to tend to some of your own).

Digital gardens are ecosystems that:

1. Dream past the colonial imaginings of gardens

Across time, gardens have been locations of colonization, classism, anti-Blackness, and racism, from the history of botany as a tool for colonization to the structural lack of access low-income Black neighborhoods have to public green spaces. Digital gardens take time to understand the complex ways systematic oppression appears in the material technoreality of digital spaces. Rather than design in opposition, digital gardens look towards frameworks outside the confines of supremacy, or to decolonized models of thought that have long existed.

2. Value pluralism and interdependence

Digital gardens are designed to value the contributions of multiple gardeners. Their design does not reward hierarchy. They strategize around design systems that allow interdependent care to be possible, consensually applied, and mutually given and received.

3. Invest in cyclical growth and sustainability

Digital gardens believe slow time is beautiful. They are designed to support us in reclaiming our time rather than being organized by it. Digital gardens reject the information highway for the clock where minutes are the lengths of easeful breath.

4. Reject linear time

Digital gardens believe time moves cyclically. They are bored of the reverse chronological feed that is the norm for the majority of social networks. They value iterative learning and adjust from conclusion as needed. They believe we should have easy access to our archives.

5. Embrace weed

Digital gardens do not believe in nor aspire to Garden of Eden-style utopias. Digital gardens reject utopias, as they both ignore the realities of our intersecting positions of power and deny the cyclical existence of harm. We all will harm and be harmed. Instead, digital gardens recognize that periods of rot, weeds, and even death are natural parts of the ecosystem cycle. They value practice over perfection.

6. Stay adaptable

Digital gardens embrace that gardens and their gardeners are ever-shifting and complex. The design of digital gardens evolves to adapt and value complexity. They embrace the design challenge of clarity that is not at the expense of its users’ dynamicism.

7. Hold safety at the fore-front, not after-front

A garden is not without tools to ensure its safety. Boundaries, defined by Kamra Sadia Hakim in their work, Care Manual, are containers housing needs and the distance at which mutual love exists. Boundaries are necessary for communal safety to be possible. Digital gardens create such protocols and give their users access to boundaries that enable transformation rather than carcerality and avoidance.

8. Look towards wonder

Digital gardens hold a component of discovery where gardeners may be delighted or surprised by what they may find. They are designed to embrace a culture of learning, where one may be open to be changed by ideas.

Digital gardens are not about creating utopias. Rather, they design towards the small and slow progress of protopias, as defined by futurist Kevin Kelly as “a state that is better today than yesterday.” We need protopias, alternatives, and the seeds of gardens. We need space to dream, and for that dreaming to connect to concrete action.

The roots of digital gardens have long been growing, and many have arrived. We see their leaves in places like Somewhere Good, a social audio app for community conversations, are.na, a social network designed for slow learning and archiving, virtual care lab, a series of creative experiments in remote togetherness, and endless other seeds. Alongside one another, we believe in each other’s collective smallness, and pull in digital gardens rooted in care, imagination, and joy.

Annika Hansteen-Izora (they/she/he) is a multidisciplinary designer and artist. They explore the intersections of design, radical Black imagination, art, and technology to create ecosystems rooted in care.

*These quotes are a part of designer Laurel Schwulst’s “Sparrows talking about the future of the web.” You can find the full collection of quotes at are.na.

Annika was also a speaker at our inaugural “Designing for Dignity” symposium with the MCA Chicago in March. Find footage of their presentation on the practice of dignity here.