The Black Reconstruction Collective on the Architecture of Equity

Moderated By Alice Grandoit-Šutka & Nu Goteh

Story Design by Rob Lewis

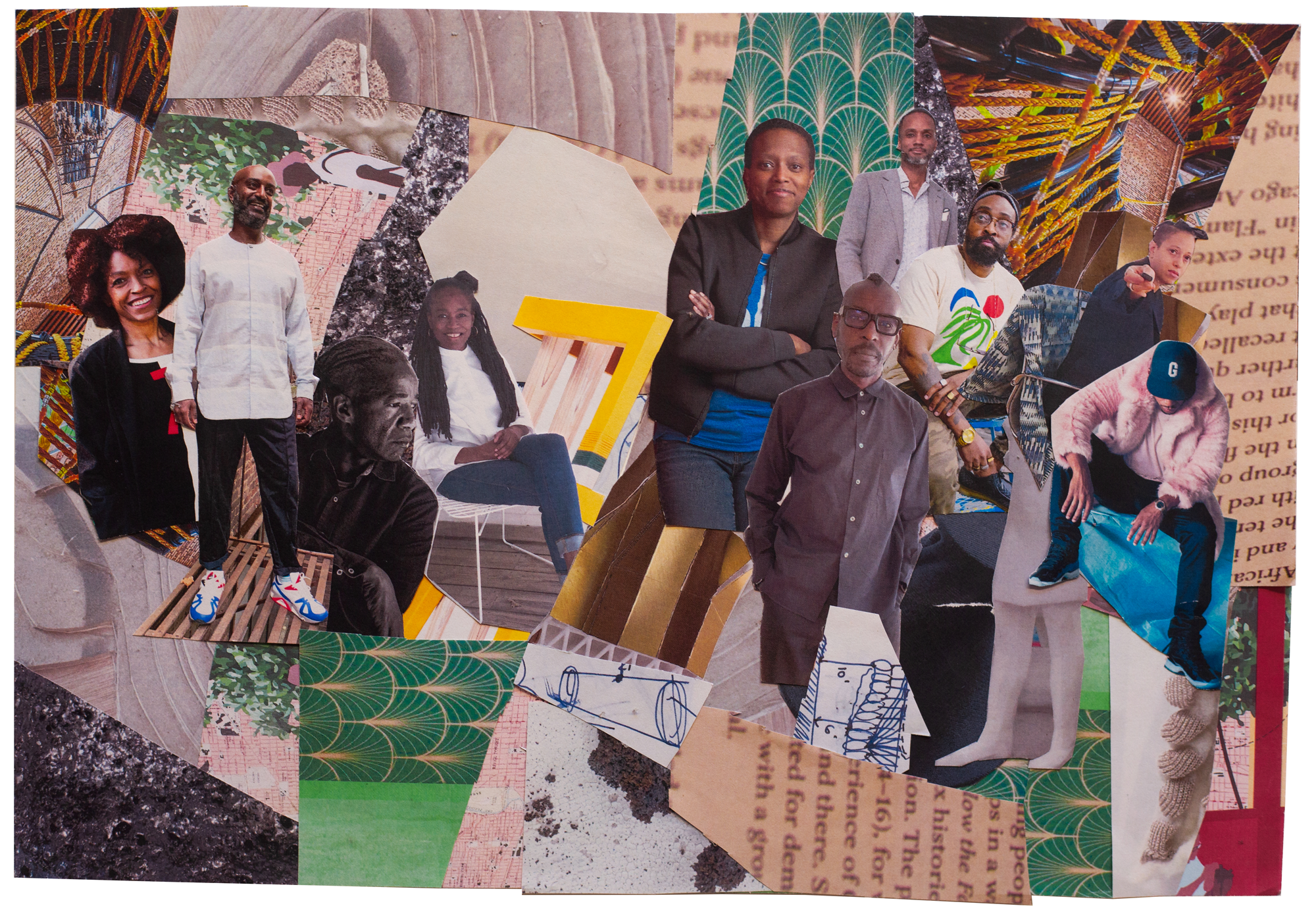

The Black Reconstruction Collective: Emanuel Admassu, Germane Barnes, Sekou Cooke, J. Yolande Daniels, Felecia Davis, Mario Gooden, Walter Hood, Olalekan Jeyifous, V. Mitch McEwen, Amanda Williams. Design by Rob Lewis.

Established in 2020, the Black Reconstruction Collective (BRC) provides varying types of support to what its ten founding members describe as the ongoing and incomplete project of emancipation for the African Diaspora—a mission we felt appropriate to center Deem’s investigation around the concept of equity.

In our conversation with the architects, artists, designers, and scholars of the BRC, we consider the meaning of reconstruction, the relationship between equity and reparation, and the role of the institution in our visions for a more equitable and emancipated future in which we work together towards honoring the fundamental synergy of all life.

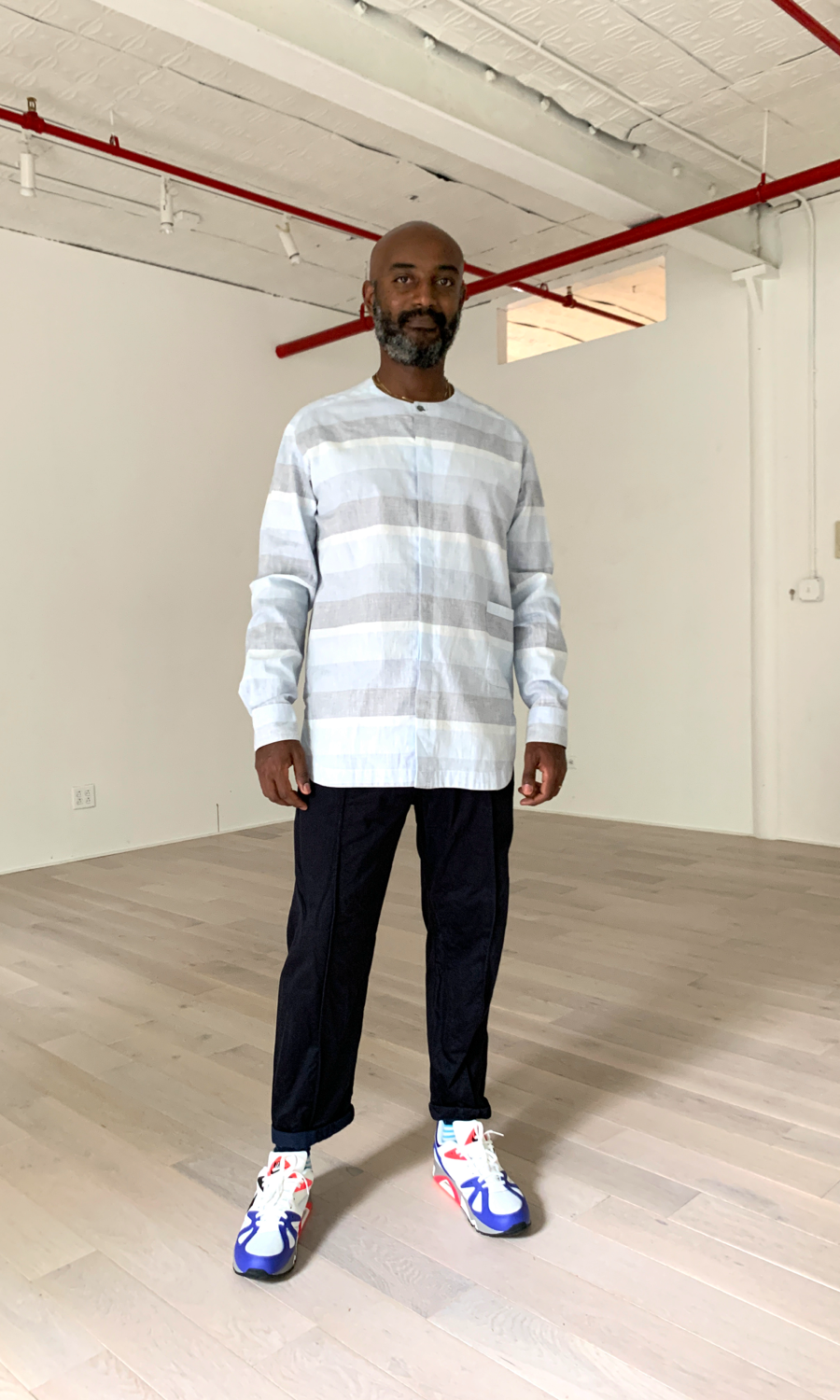

Members of The Black Reconstruction Collective: Germane Barnes, Amanda Williams, Walter Hood, J. Yolande Daniels, Sekou Cooke, Emanuel Admassu, V. Mitch McEwen, Mario Gooden, Felecia Davis, Olalekan Jeyifous.

ALICE GRANDOIT-ŠUTKA

This issue of Deem is centered around unpacking the concept of equity. To anchor our conversation, could you share some insights on how the Black Reconstruction Collective (BRC) came about? Was there a particular catalyst in forming a collective?

EMANUEL ADMASSU

The BRC came together because of the 2021 exhibition “Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America” at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). However, the collective itself was formed because we were invited to make and exhibit work at a museum that wasn’t structurally capable of hosting such a show. Forming a collective became a way to apply pressure, because that institution was basically designed to make sure that people like us don’t exhibit in that space. I think that is what brought us together.

SEKOU COOKE

Mitch is at the heart of the genesis of the collective. Mitch, would you like to chime in on that?

V. MITCH MCEWEN

That’s Sekou’s way of saying that I was naive enough to have started an architecture nonprofit before. Part of what I brought to the early initiative was the impetus that we could be stronger together, like Voltron, and also share resources and knowledge. Having created a nonprofit in the past, I brought to the table the conviction that we could do it. Nonprofits, especially in architecture, can seem very daunting, particularly as many of them are over a century old. But, in actuality, an organization can be as malleable as you need it to be.

FELECIA DAVIS

The BRC came together after our first meetings with the curators and advisory board at MoMA. It was a weekend morning, we had just seen each other’s work, and we were really excited to continue the conversation. We were also talking about how we would fund this work, because the museum had not provided adequate financial support. That was a big part of the impetus for forming BRC; we wanted to create a place where others, in the future, could make and share the kind of work that may not truly be supported by an institution like MoMA.

GERMANE BARNES

Most things that Black people do these days are invented because they have to be. You’re given crappy circumstances, now find your way out of those crappy circumstances. We found out we would only receive $8,000 for the entire production of the show—from a massive institution— and also that we wouldn’t receive that full sum upfront. They gave us a portion to start but made us wait until everything was done before releasing the remaining amount.

I distinctly remember one of our conversations, in which Sekou mentioned,“I need some more money, man” and we all agreed, “Yeah, a lot of us need more money.” One obvious inequity is that many of us have an institutional tie, and therefore have more resources that we’re able to pull together, but then there’s this assumption that we can just go to our universities and secure additional funding to cover the gap—that was the underlying message we received. Some of us, myself included, asked other participants who had been part of the “Issues in Contemporary Architecture” series before, “How much money did they give you?”

Everybody gave me the same answer: about $6,000-8,000. But, if you’re with MOS Architects, that’s nothing to you, because you have a full workshop, so who cares? If you’re Jeanne Gang, you have an entire multimillion dollar company. That’s a drop in the bucket. But if you’re a single practitioner or somebody who doesn’t have those resources, you do what you can to pull it together, and that’s what Black people have always done.

SEKOU COOKE

The money question is incredibly important. I can imagine a parallel narrative of how the BRC was formed that assumes we’re a group of people who have known each other for a long time and decided to start this collective based on our shared values, desires to transform architecture, and all the different ways that we see Blackness working. But that’s just not the case. Sometimes, especially for the Black community, it comes down to “Can we afford this? How can we afford this?” And out of that necessity comes something like a BRC, something that can challenge a massive institution like MoMA to do something different, or that can change the paradigm of how people lecture in architectural schools. But it still starts with the fact that we were given $8,000. Is that our stipend? And then they’re going to pay for production, right? No, that’s everything. We had to come up with multiples of that sum in order to make the show happen. But, in the end, BRC has become something powerful enough to raise even more funds to do more powerful things.

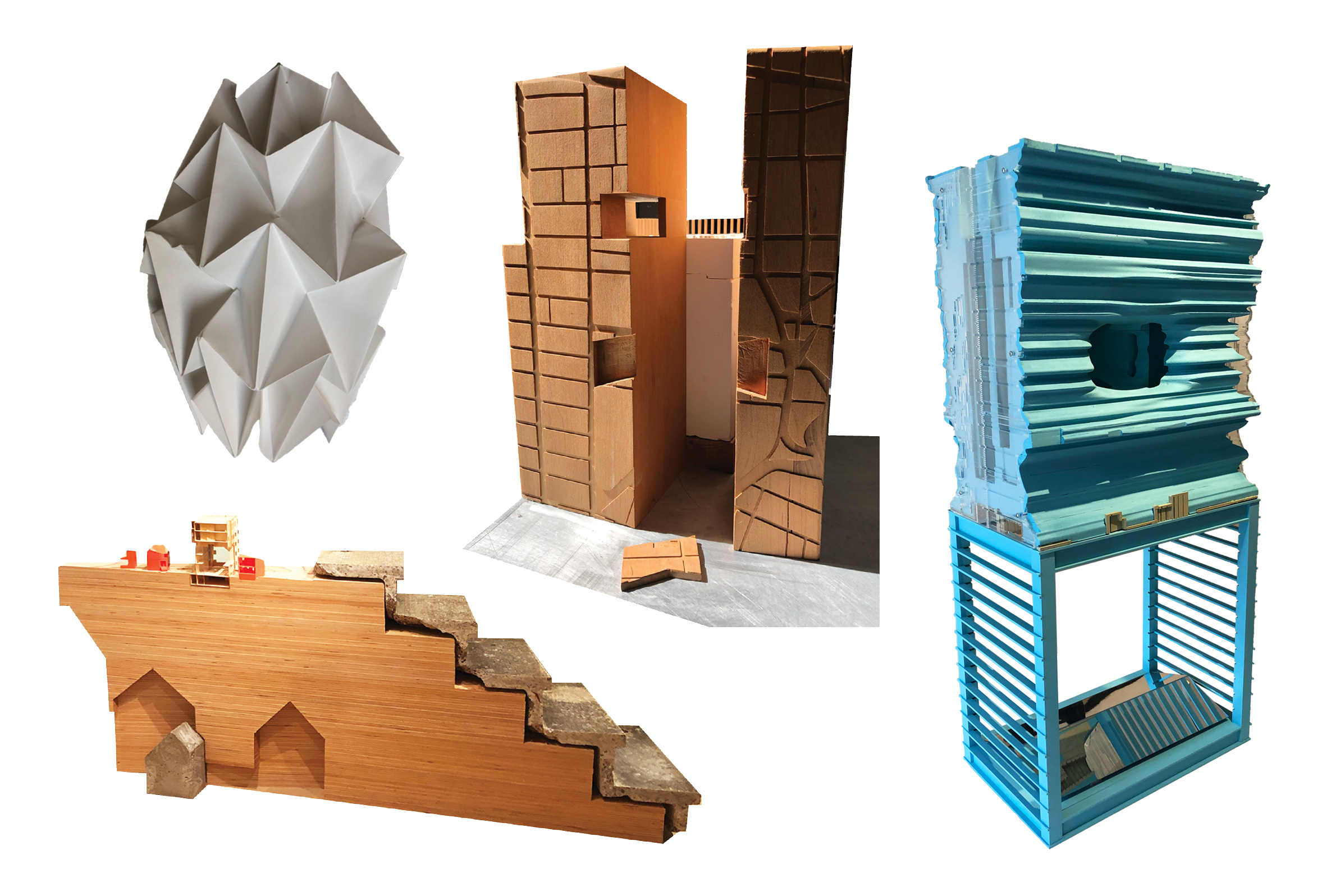

Top left and center: Paper model, image courtesy of Felecia Davis. GSA call for The African Burial Ground; cherrywood and plaster model, image courtesy of Felecia Davis. Bottom left: Sekou Cooke, We Outchea: Hip-Hop Fabrications and Public Space, 2020. Far right: J. Yolande Daniels, Black City: The Los Angeles Edition, 2020.

NU GOTEH

In BRC’s manifesto, you specify that this work is not rebuilding, but reconstructing to the core of governance, citizenship, history, infrastructure, and the distribution of land. From a design perspective, what does reconstruction mean and involve?

V. MITCH MCEWEN

This is a big question, but let’s start with the definitive difference between rebuilding and reconstructing. Rebuilding is a paradigm of stasis. When we think about crises, when we think about Hurricane Ida, we think about these ongoing crises of denial. Rebuilding means you are literally remaking the same thing that was there before. Reconstructing is distinct from rebuilding. Part of what I think it opens up is a temporal shift. Reconstructing implies deconstructing, implies rethinking, implies different forms of not just building, but of determining who is responsible for imagining the future.

EMANUEL ADMASSU

Reconstruction has dismantling embedded within it. The ambition is first to dismantle the spatial systems and conditions that are devaluing Black life, which also means we need to imagine a world that is not built on racial hierarchy. Reconstruction is the simultaneous action of making sure we are disassembling the current world, while also building another world at the same time.

SEKOU COOKE

I read the statement as challenging some of the precepts of architecture itself. Architects are trained as object makers. But we’re not only interested in rebuilding buildings. We believe our practices can go beyond that, to talk about governance, citizenship, history, and infra- structure. We are hoping that those of us working in the creative fields—in architecture, design, and the visual arts—can actually go beyond making pretty things to affect the structures that shape our lives in broader ways.

MARIO GOODEN

I’d add that, particularly in consideration of history, when we think about reconstruction, I would personally put a hyphen between the “re” and the “con,” in that I think that there is quite a bit of invention there; if we think about our ancestors during the period of reconstruction, they weren’t remaking, they were inventing. Perhaps this gets back to the first question, too, and the desire to not need to rely on the benevolence, if you will, of an institution, government, or system, and instead to focus on reinventing these systems. As others have shared, that’s the important lesson about the formation of the collective: we came together out of a practical need, and the recognition that the institution is not capable of handling us, but out of that came the realization that we need to invent something else.

FELECIA DAVIS

For the last few months, we have been figuring out how we want the BRC to function as a collective. Dealing with everyday organizing and figuring out how we want to be in the world has thrown that question back at us every single day. How can we avoid reinstating the status quo? How can we break down the gender barrier? How can we transform inequity? These concerns are embedded in all the small and practical things that we do, as well as in the art that we make. This has been, at least for me, hugely philosophical, as well as practical. How does one go about doing day-to-day things?

J. YOLANDE DANIELS

From a design perspective, reconstruction means shifting from and cracking open the dominance of the Western and modern paradigms that are the foundation of the arts and architecture. It means owning a “double consciousness” in which the once unacknowledged narratives and histories of the achievements of Black and non-white people sit on an equal plane. It means unpacking the theories and tropes of the “primitive,” “dominion,” and “progress” that are the foundation of “modernity.” It means acknowledging the importance of intercultural influences in advancing the arts, revisiting histories, and devising new means and new paradigms.

An example of this is the 2019 work Colonialism and Abstract Art by artist Hank Willis Thomas—a reconstruction of the diagram “Cubism in Modern Art” created by the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, Alfred H. Barr Jr., in 1936. Thomas’s rendition adds the unacknowledged histories and structures of colonialism that were critical components of this art form.

The architecture of reparations in my work includes looking back in order to project forward. For me, the projection of new forms (of urbanity or domesticity, for example) is dependent on the analysis of the production of the present forms. Context is central to subversion. My desire to subvert the spatialization of power relations from a Black perspective has required that I first study the forms in place, and it has led me further, to search for traces (i.e. evidence) of the spatial stories of African Americans.

From left to right: Cone study, image courtesy of Emanuel Admassu. Model, image courtesy of Walter Hood. The Refusal of Space, 2020, image courtesy of Mario Gooden. Seating sketch, image courtesy of V. Mitch McEwen. Models, image courtesy of Felecia Davis.

ALICE GRANDOIT-ŠUTKA

We have been examining equity through two parallel definitions—one is about the value of shares in a whole; the other is about remedial justice. I’d love to hear more about the architecture of reparations that BRC has proposed. What is the relationship between reparations and equity? Are reparations necessary for equity?

GERMANE BARNES

These are very heavy questions, and, in my humble opinion, at this stage of BRC, we may be unequipped to answer this. We’re still making sure that our mission is aligned with the actual things that we’re creating on a daily basis. Somebody can correct me if I’m wrong, but, at this stage, I would say that we are redistributing funds that are given to us, but I don’t know how that identifies at the level of reparations. The word “reparation,” I think, would insinuate that we are also the oppressors, while in fact we are the people who were wronged. Maybe there’s a different word that’s more accurate to what we’re doing.

AMANDA WILLIAMS

I think that our actions constantly call into question all of the complexities of equity. For me, it’s impossible to have any kind of conversation about equity without talking about power. I think Germane is saying that it gets tiring that those who’ve been persecuted are also those tasked with figuring out how we’re going to get out of a situation we didn’t create. I love the line in our manifesto that says,“Paradoxically, the people who did the constructing and must now do the reconstructing are likely to be the same—laborers in one instance and authors in another—designers of this nation and of themselves.” This conversation is always had with the people who are seeking equity, and never had with the people who perpetuate the inequitable situations in the first place.

A conversation about reparations throws into question issues of power. Equity is the byproduct. This is also why I hate the word “diversity.” Diversity should be the byproduct. But, as we have yet to observe any semblance of racial equity anywhere in the history of the United States, dare I say globally, it’s hard to then be the people who have to figure out how to make it happen and, in our case as makers, what it should look like. Somehow, we were all signed up for this world-building exercise, so we’re constantly engaging with it and talking about it. I didn’t take the question as being about direct reparations, in terms of some kind of legal or financial outcome, but rather the idea of continuously challenging how things are and how they should be.

MARIO GOODEN

I’ve been thinking about this question as I’ve been working on my syllabus for school, which starts next week. First, I think that equity should be separated from reparations, from diversity, and from words like “inclusion” because I think equity is a practice. It doesn’t necessarily stop. A person or group might receive reparations, but equity is an ongoing thing that is continuously being produced.

I loathe the acronym DEI—diversity, equity, and inclusion—because, looking at equity between those two words, one first has to ask,“Well, diverse from what?” and then, “Be included in what?” The answer is always the baseline of whiteness. When we think about equity, I think we need to divorce it from that baseline of whiteness, so that we’re not evaluating ourselves within a system which we already know is flawed. Again, it comes back to this notion of reconstruction and invention, in terms of the productive aspect of trying to make something equitable. That brings me to Germane’s comment—we’re not there yet, at least in terms of equity itself, because equity is a constant. We can’t achieve it and then be done. We must create equity every day and in every situation.

“From a design perspective, reconstruction means shifting from and cracking open the dominance of the Western and modern paradigms that are the foundation of the arts and architecture.”

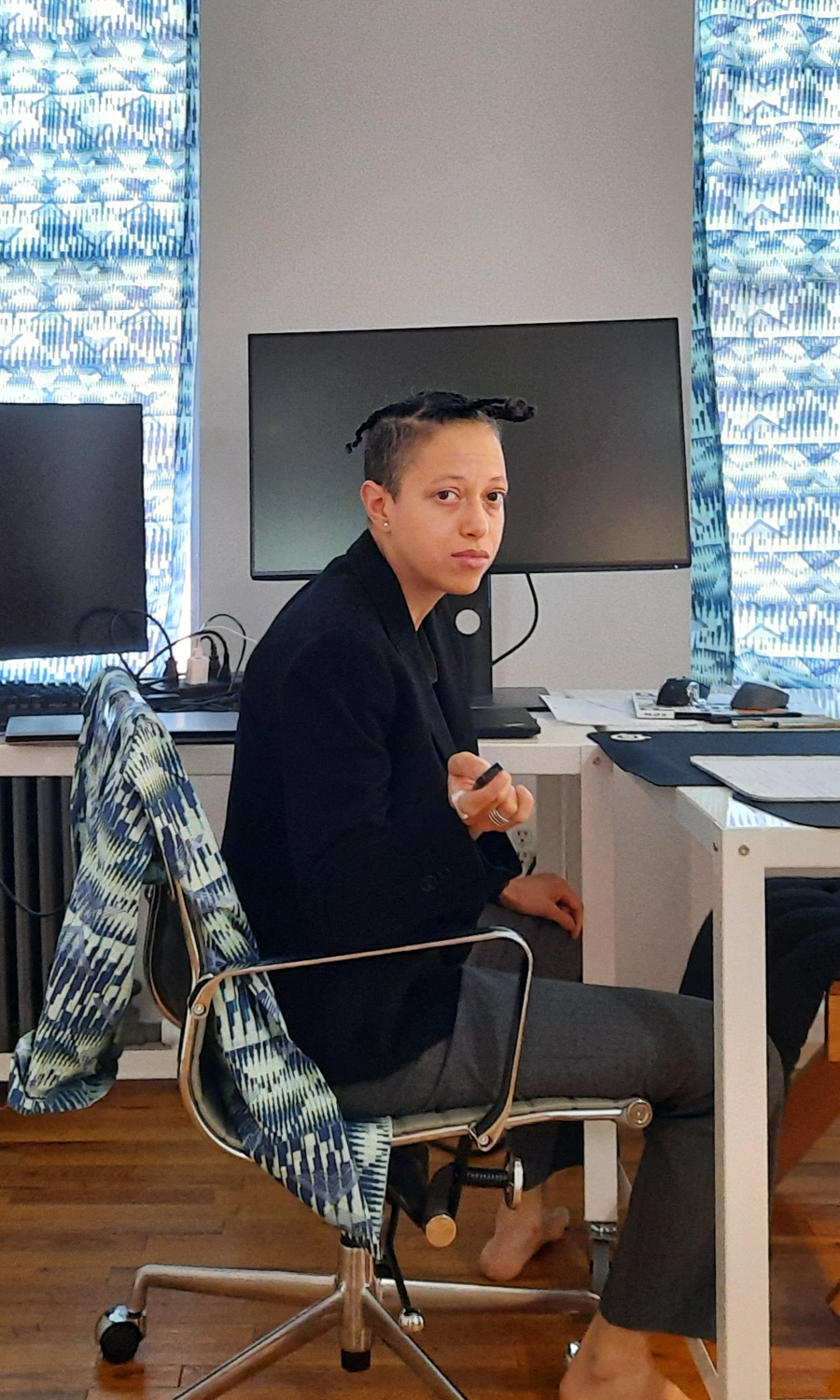

Image courtesy of Germane Barnes.

OLALEKAN JEYIFOUS

Our first board meeting, with Saidiya Hartman, Tina Campt, and others, really got us energized, particularly around acts of refusal and the question of legibility. I’d like to discuss these ideas in terms of the kind of work that we produced for the show, as well as how I think through the BRC as a collective. I feel the question frames a structural way of looking at equity, reparations, and reconstruction, but it also presumes a familiarity with or understanding of the kind of creative output that we’re bringing. However, the work we made for the MoMA show wasn’t necessarily readily understood and didn’t always fall within conversations around capital “A” architecture.

What does Architecture look like? There were questions from higher up curators that seemed to ask whether we, as participants in the exhibition, knew what architecture was. Not only do we know what architecture is within this particular framework, but we also bring so much of our own experience and nuance, in terms of navigating these institutions, into our own work. That is why establishing a platform for Black creatives and practitioners is also about making a space in which their work can be understood beyond the white Western canon of what constitutes architecture.

We’re still moving toward the ability to look at work by ten Black architects and have some sort of precedent for understanding how to approach it, because there was such a gap between shows of this nature. In the process of making this show, it became very important to me to think in terms of spaces, platforms, and audiences where our work can be received, appreciated, and understood, in and of itself, without being otherized.

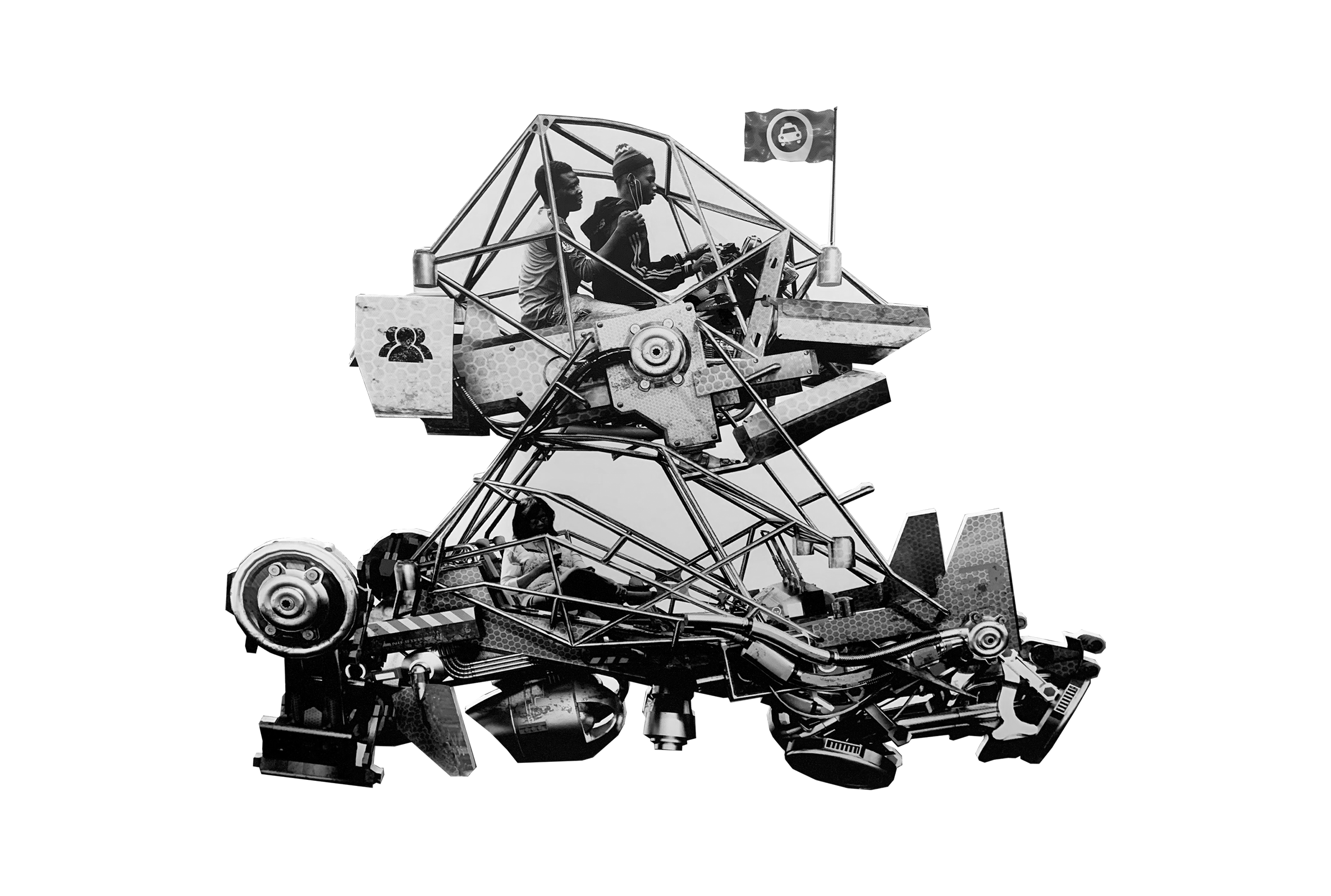

Olalekan Jeyifous, Anarchonauts.

WALTER HOOD

I would add, in regard to the idea of equity, that, in the past, the work of Black and Brown artists and designers has been historically devalued. The notion of coming together, to me, gives it value. Having a show and forming a collective through an act of refusal gives the work value. We are beginning to understand, from within, what that value is, and that we don’t need the outside to tell us what it is. I think that could be a very powerful way of moving forward, because through the BRC we can begin to define where value lies and where value might accumulate. And it’s not just monetary, it’s cultural, too.

V. MITCH MCEWEN

I tend to take terms like “equity” overly literally because I wasn’t educated as an architect. I studied economics and development first, and I worked in finance. To be honest, I’m still looking for architecture to be halfway as radical as finance. I think what finance gets away with, through its terms of financialization, is just bizarre. To give one example—the quantitative easing that the Fed has been doing for the past decade is a trillion dollars that we don’t talk about, asset purchases with names like Operation Twist. These are reparations for whiteness, for facilitating the normalcy of things like the yield curve. When we talk about architecture and reparations, we’re actually opening up something other than equity. Of the two definitions you offered, I’m more drawn to the one that talks about sharing the whole. And, within that definition, I’m interested in how architecture can first reimagine the whole and then reimagine its partitioning.

We have the capacity, as a field, to facilitate radical changes on the ground. One of our upcoming projects that I’m super interested in is UnMonuments. How can we take from the ideas we’ve been investigating and actually engage these sites? For me, I’ve scaled that down to thinking about a specific housing project in New Orleans as a place that was stolen—stolen in the sense that Fred Motel talks about in Stolen Life (2018), but also literally stolen in that you can track how the Iberville projects were actually not flooded after Katrina, but were treated as if they were so that they could be privatized.

J. YOLANDE DANIELS

The BRC has made furthering the Black radical tradition part of our mission. While the Black radical tradition has largely been defined through creative production, the emphasis today is on joy and acknowledging that we are enough. This has brought attention to the subversive or radical act of survival. If “surviving while Black” is itself the most radical act in the face of paradigms which demean and erase signs of habitation and progress, then knowledge of the tactics used to subsist and subvert is what I want to place in my tool-kit. This tool-kit is not nostalgic, resists essentializing pure origins, and values and opportunistically draws from all people to process useful lessons, directed toward the liberation of Black people and other folks. It seems to me that equity is more nuanced than equality—equity is applied, unlike equality, which is a theoretical or symbolic concept. Equity, by definition, has an emphasis on fairness and distribution that implies that repair, or reparations, may be needed to produce fairness.

“We have to collectively survive and thrive on this planet. There is no such thing as an individual liberation. If we truly believe in liberation, then the idea of shares within a whole is fundamental to what we’re trying to do.”

SEKOU COOKE

I tend to think about these questions less from a problem-solving perspective and more as radical opportunities to do something different. I keep thinking back to a diagram that’s been popularized over the last year and a half, which illustrates how the concept of equity differs from that of equality through an image of three people trying to look over a fence. Equality might mean the playing field is level, but also that only the tallest person can look over the fence. Equity would mean people of different heights receive boxes to stand on that correspond to their height, so that they can all look over and see the same view.

In terms of reparations, the easy solution is, “Let’s get these short people bigger boxes,” but this fails to recognize the built-in assumption that Blackness is equated to shortness. The truth of the matter is that we didn’t start out short. Maybe we started out even taller than the guy who can see over the fence, but somebody came and chopped our legs off.

Reparations can’t give us back those legs, right? What we’ve been doing instead is creating prosthetic legs that allow us to operate in the same way as someone who never lost theirs. From there, my imagination goes wild. What if we use those prosthetics to kick down the fence, or to step over it? In other words, we’re not going to sit and wait for reparations to happen; the very lack of equity we are facing is allowing us to create something different, something new, something that challenges whatever existed previously.

EMANUEL ADMASSU

Quite simply, I think of reparations as the first phase on the long journey towards liberation. By reparations, I’m not talking about cutting a check, which is what everyone assumes. To me, reparations means completely redefining our value systems. For example, some folks, especially contemporary artists, are thinking about ways to decommodify land.

If the colonial project made land an object to divide and sell, then the beginning of reparations is to say, “No, we’re not going to treat it as a commodity.” This ties into the other definition that we’re working with, which is a rejection of any form of individuation. We have to collectively survive and thrive on this planet. There is no such thing as an individual liberation. If we truly believe in liberation, then the idea of shares within a whole is fundamental to what we’re trying to do.

NU GOTEH

How can architectural representation also be a metaphor for other kinds of space and occupancy? What kinds of spatial practices does BRC engage in?

AMANDA WILLIAMS

I’m constantly intrigued with the idea of autonomy over self. Maybe that’s actually in contradiction to what Emanuel was just saying about a rejection of the individual, but if I can’t even guarantee that my body can stand here [points to the ground] for as long as I want it to, I don’t quite understand questions about spatial dominion over more than the square foot that I occupy. I get exhausted imagining what else could happen at any given moment. I’m trying to move out of fixating on that to think about control, which is tied to liberation and joy in a larger sense. We’ve all worked on projects, either individually or collectively, for which we’re ruminating on, remembering, or imagining moments when we experienced autonomy. I’m always stuck there, and maybe not in a good way.

GERMANE BARNES

Should we be answering this individually, or as the BRC?

NU GOTEH

Whichever you prefer.

OLALEKAN JEYIFOUS

I think that’s the beauty of it, right? The BRC is made up of ten very distinct individuals with ten very distinct practices and approaches to even the most fundamental questions about what architecture is and where value lies within the creative output we each engage in. Questions like this have been part of our internal dialogue around trying to find a philosophical and political throughline with which we can lay the groundwork for doing something very clear and practical with this organization. Our manifesto is lofty, but it’s also grounding. We’ve had numerous conversations around where our own individual practices feed into the collective’s position. As Germane said earlier, some of us are tied to institutions, some of us have studio practices, and Amanda and I operate more as individuals. You’re seeing the very diverse trajectories of architectural and spatial practice. One goal of mine is simply to have Black scale figures easily available for placement into architectural renderings. We often expend a significant amount of energy searching for Black scale figures. I want to have a download link available to every architecture student in the US and abroad, so that when they present their midterm reviews, many of the scale figures in their projects will be Black. That, for me, is one attempt to broach this idea of “equity,” even on what may appear to be the most trivial level.

V. MITCH MCEWEN

I want to piggyback on that because there’s something important about the technical. There’s a lot of technical, speculative work that has an imaginative and even science-fiction-like quality. I was telling Amanda that last month, I went back and looked at the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), which was created by Malcolm X in 1964. I had forgotten how obsessed with it I was as a kid. The first thing I ever designed, in the seventh grade, was a memorial for Malcolm X. At the core of the OAAU was the idea of technical exchange. To me, what happens with the sharing of something like scale figures, or even with the juxtaposition of work in our MoMA show, is an exchange of Black imaginary and technical capacity. It’s different from representation in the metaphorical sense.

FELECIA DAVIS

There really isn’t a collective without us as individuals, and each of us operates like a thread into other spaces. We are constantly oscillating in all different directions, then coming back into BRC bearing witness from outside. That is spatial. I think it’s really important that we exist in these different worlds and then come together to tug and push against each other with our ideas. I really like this question.

“We are constantly oscillating in all different directions, then coming back into BRC bearing witness from outside. That is spatial.”

Smith College—Matterful Black Lives Tea Set study. Image courtesy of Amanda Williams.

NU GOTEH

Our last question is about institutions. Some of us work within institutions, some of us work alongside them, some us work outside of them. What, if any, is the role of the institution in the struggle for equity?

AMANDA WILLIAMS

We’ll tell you in twenty years! We’re making a new institution, so we don’t know yet.

SEKOU COOKE

We need new institutions. Our current institutions are not going to play the role that they need to. They’re like massive oil tankers— trying to turn them around would take forever. But it’s still critical to understand how institutions work from the inside. I think all, or most, of us are connected to some institution, but even institutions of supposed “higher education” are still run like corporations. We’re learning the skills and techniques from the inside to create the change from the outside. We don’t know yet whether this specific new institution that we’re attempting to create will be capable of doing exactly that, but we wouldn’t be embarking on this journey if we didn’t think it was possible.

ALICE GRANDOIT-ŠUTKA

There’s a quote from William Haver that inspired this question. He writes, “Let me be blunt. I do not think there has been, is, or can ever be, an equitable institution. Institutions do not, cannot, by virtue of their institutionality, be equitable.”

EMANUEL ADMASSU

As long as we refuse ever becoming fully-formed and make sure that we stay in the space of incompleteness, then I think we have a chance. The moment we become “institutionalized,” we lose the game. Listening to Mitch made me think of a book I just read, Worldmaking After Empire (2019) by Adom Getachew. It traces the history of liberation movements on the African continent. There’s always a brief moment of radical change happening, then within a few years you see it all fall apart. We need to figure out how to stretch that moment for as long as possible. The way we’re doing it so far is by de-centering the ten of us and making sure that BRC becomes about the fellows and the people we’ll be supporting financially and intellectually.

GERMANE BARNES

An institution’s primary goal is always protecting their brand. Should equity be a subset of that brand alignment, then, by all means, they’ll advocate for it too. But we know that in most cases, that’s not really what the institution is going for, because that’s when the money stops. For the BRC, I don’t know if I’d use the word “incomplete,” like Emanuel. I like the word “evolving.” Incomplete implies we’re not where we want to be, but that’s because we are constantly pivoting or revising our goals, not to mention there are ten of us with ten completely different points of view. One of the goals I always put forth in our meetings—as somebody who is of the people and for the people—is that we work more with the people. I don’t care about big institutions or Ivy league schools. I would rather go hang out at the HBCU. That’s where I want to be.

FELECIA DAVIS

You’re definitely going to get ten different opinions on this. Some people are interested in working on the inside to transform from the interior. Others are interested in walking away and building something completely new. We are always going back and forth on this question.

WALTER HOOD

I do think that institutions have served as resources for many of us, and that we have tried to utilize those resources in a transgressive way. I personally have given up on the institution changing because, in the twenty-five years that I’ve been on the West Coast, it has actually reverted back to what it was prior to the push to reform it. As a professor, I have certain resources, like students and space to convene, but there are other resources out there that are not tied directly to institutions.

AMANDA WILLIAMS

I think we should contemplate the question of organizing in lieu of, or perhaps alongside, institutions. As someone who has opted to work singularly, I’ve given a lot of thought to something as banal as how one (via American tax code requirements) is required to form oneself as a business entity. These requirements make opting to not be a “structure” or entity nearly impossible. A push to a certain kind of institutional existence is baked into these kinds of documents. So what does organizing, both informal and formal, look like? What does its cousin, collaboration, have to do with it? I agree with Haver, but is that because I can’t escape a capitalist lens for defining the word “institution”? We’re all referencing things we’re inside of or have rejected (mostly architecture schools and design firms). I’m excited when BRC has conversations about taking time to research past Diasporic movements, not necessarily existing institutions.

MARIO GOODEN

For me, the question of the institution is tied to the question of hegemony. Regardless of whether we’re talking about an Ivy league school or a Black church, what the institution needs to do is get out of the way so that things can be produced and can evolve. Sometimes that may mean that the institution needs to be dismantled or abolished. Other times, it may mean that a new structure needs to be formed. I take this question as, “How can we not get in the way of each other as we move towards liberation?”

The Black Reconstruction Collective: J. Yolande Daniels, Emanuel Admassu, Walter Hood, Felecia Davis, Amanda Williams, Mario Gooden, Sekou Cooke, Olalekan Jeyifous, V. Mitch McEwen, Germane Barnes. Design by Rob Lewis.

Emanuel Admassu is co-principal of AD—WO, an art and architecture practice based in NewYork City, and an Assistant Professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation.

Germane Barnes is the Director of Studio Barnes and an Assistant Professor at the University of Miami School of Architecture, where he directs the Community Housing and Identity Lab.

Sekou Cooke resides in Charlotte, NC where he runs the design practice sekou cooke STUDIO and is an Associate Professor and Director of Urban Design at UNC Charlotte School of Architecture.

J. Yolande Daniels is a partner at studioSUMO, with offices in Los Angeles and New York, and an Associate Professor at the MIT School of Architecture + Planning.

Felecia Davis is Principal of Felecia Davis Studio,an Associate Professor at Pennsylvania State University, and Director of SOFTLAB@PSU.

Mario Gooden is a Principal at Huff + Gooden Architects in New York and a Professor at Columbia University GSAPP, where he is the co-director of the Global Africa Lab.

Walter Hood is the creative director and founder of Hood Design Studio in Oakland, CA, a Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and a MacArthur Fellow.

Olalekan Jeyifous is a Brooklyn-based visual artist who examines contemporary socio-political, cultural, and environmental realities through a sci-fi lens wrought with a synthesis of architectural utopian and dystopian ideals.

V. Mitch McEwen is Principal of the design practice Atelier Office in Harlem and Assistant Professor at the Princeton School of Architecture, where she directs Black Box Research Group.

Amanda Williams is an acclaimed Chicago-based visual artist whose work investigates color, race, and space in the city while blurring the conventional line between art and architecture.