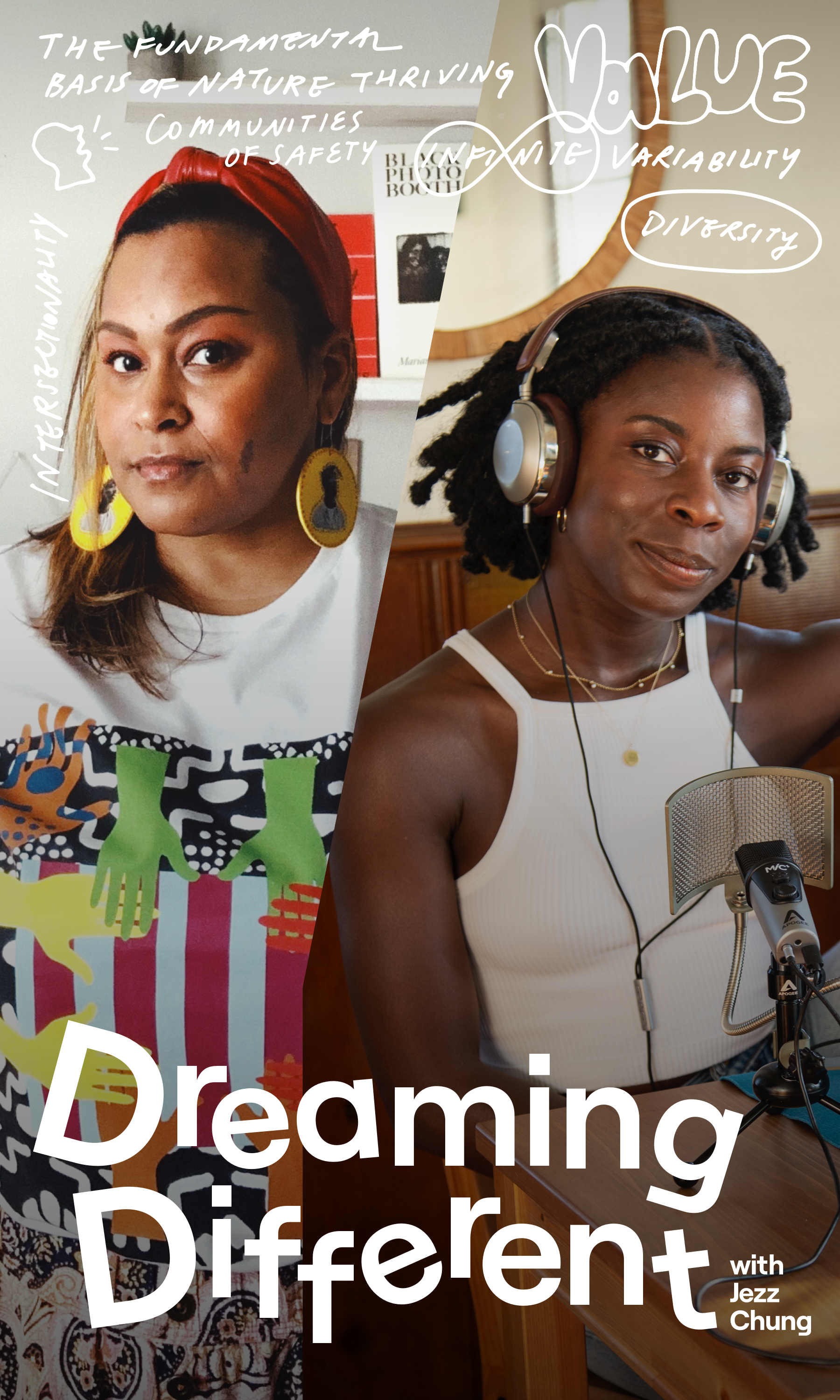

The Science of Neurodiversity and the Art of Advocacy with Dr. Yewande Pearse and Jen White-Johnson

Audio engineering by Hasan Insane

Episode Two of “Dreaming Different” brings together a neuroscientist and a disability justice educator to discuss the art of advocacy and the science of neurodivergence.

Dr. Yewande Pearse (@nyewro) and Jen White-Johnson (@jtknoxrox) discuss the medical and social models of disability, debates surrounding these paradigms, and what it means to find language that helps identify your needs.

Listen on Spotify | Apple Podcasts | Google | Stitcher | Amazon Music | Pandora

“We have to show up in so many different spaces as so many different versions of us, and that is an art form. That is a science. To be able to do that and have the power and the means and the capability to do that.”

—Jen White-Johnson

Transcript

Jezz

Welcome to Dreaming Different! I'm your host Jezz Chung and today's episode we're going to be getting nerdy nerdy nerdy with Jen White-Johnson and Yewande Pierce and this is a reunion episode continuing a conversation that we started actually about a year ago in January 2022. And we'll talk more about how we were brought together. But I'm going to start us off with a visual description of myself. I am Korean, I have long black hair that's pulled back right now into kind of a slick ponytail, I have on an orange tie-dye top from this Korean owned brand called Sundae School and I am sitting in front of a white couch. My wall is kind of this purple pinkish color and I have on the wall some framed photos that are colorful. Jen, do you want to give us a visual description of yourself?

Jen

Yeah, sure. Hi, I'm Jen White Johnson coming to you from Baltimore, Maryland and I am an Afro-Latina woman and my skin is cinnamon caramel brown and I'm wearing my favorite caramel wide brimmed hat sort of kind of like my little protective device for crazy hair days and I have kind of lightish honey blonde tresses of hair that are flowing on my shoulders and I'm wearing cream colored glasses. And I have on very simple silver hoops and I'm wearing a very loungey gray tee that says University of Motherhood. Very chill day. And I'm actually in my studio and behind me is a whole bunch of artwork uplifting disability justice and Black people and Black lives. So thank you.

Yewande

I'm Yewande Pierce. It's so good to be reunited with you both Jezz and Jen. I'm coming to you from Los Angeles via well, I'm originally from the UK. So I'm a Black British woman. I have dark brown skin. Today I've got my hair piled on top of my head. My head has these locs and I was ready for this episode so I've got my headphones on and my mic. But in the background I've got loads of plants— have a bit of a plant addiction— and it just never stops. So I've got a nice variety of green and I'm actually sitting in my dining room which has a really nice arch between the living room and the dining room. I live in one of those kind of 1940s Spanish duplexes I think it would be described in LA, and it has all of the original grandma fixings. So yeah, it's really cozy and yeah, I'm happy to be sharing the space with you guys today.

Jezz

Yay! Very cozy. And for those of you who don't know, we did a conversation in January about kind of I guess it was just an introduction to neurodiversity. It was a neurodiversity forum that we did with Deem and the response to that…I want to hear kind of how the response to that for ya’ll has been too but for me I've gotten so many random messages and one time I was at a friend's party at this bar in Bushwick in Brooklyn here in New York and the bartender kind of leaned over and was like “[gasp] oh my gosh I watched that neurodiversity forum and I've been sending it to everyone I know and it's changed my life.” And I was so amazed that it moved someone that much because I think for me I've been so immersed in this language, I've immersed myself in this language as soon as I discovered it. And it changed my life too. So I guess every time we even say the word neurodivergent or talk about the neurodiversity paradigm, the neurodiversity movement, I think it really does impact people. So, we're here today to continue that conversation, continue that dialogue and talk about our experiences and our relationship with neurodiversity and the science behind it. But what has it been like for y'all since then and I'll kick us off with the question: what are you thinking differently about lately?

Yewande

That's amazing to hear that it had so much impact and that you were just out in the world and when you're doing these things you don't really necessarily…you're not aware of the reach. So that's really amazing to hear. I'd say definitely the same. Anyone that I shared the conversation with both of you all, oh my goodness even myself after the conversation I felt like I didn't really stop thinking about it. I feel like I've still been thinking about it to be honest and I think just this neurodiversity language feels like it really invites people in and welcomes people in a different way than maybe previously before we had that language. Definitely for me, the fact that it doesn't have a formal definition and it can encompass so many things really opens a conversation to people. The number of friends I've had who themselves have started to maybe identify as neurodivergent is the thing that really surprised me. I've had family members be like you know what, I'm thinking that actually... Take ADHD for example. It's historically been identified in a very specific kind of person so I think that yeah, it's really just been an ongoing conversation. And you asked what have I been thinking about recently. The timing was pretty great in that I had just started exploring the idea of neurodiversity personally but then had been invited to participate in this amazing opportunity with Deem to write this piece and have this conversation with both of you and explore it further but I also just got a job in corporate and so having this new really comforting space based in the social paradigm of neurodiversity community and then going into a corporate environment where it it feels like it’s so behind, it doesn't exist, has been really jarring. So I guess one of the things I've been thinking about a lot is how it really feels to contort yourself to fit into a corporate environment where there are still so many risks associated with embracing that language. Especially when you found that comfort within a social environment.

Jen

Yeah, that's beautiful. I mean and just to be in community. And this is Jen. I feel like I was just really happy to just be in everyone's ether that day you know to be among everyone's presence and to just to just feel like I could be authentic and I could just be myself. And I mean I've been a fan of Deem for quite some time and to see the attention given towards neurodivergent creatives was just exactly what I needed to see and I was just very happy and I knew that the issue was coming out and I had shared it. I had wanted to begin getting connected to Yewande and to Jezz and then that's when Deem reached out and said hey, you know we want for you to be also a part of this initial conversation to bring the issue to life and I was like wow because I wasn't featured or interviewed for the actual magazine or for the issue so I sort of kind of felt like well do I still have a place in this conversation, will folks embrace myself even though I wasn't necessarily featured in the issue, will I have the same impact. But I just really love how Deem understands that the conversation is ongoing and the conversation continues to evolve and more voices and new voices can continue to be a part of the conversation. And that in itself has allowed for me to continue thinking differently and the conversation just affirmed that thinking differently is exactly what I'm meant to do and what is supposed to be happening specifically. You know in terms of myself as a neurodivergent artist with ADHD and then also parenting a neurodivergent child who's autistic and again, feeling like I can be in community and that all of my sentiments and all of my longings can be affirmed.

Jezz

Mmm and I love that within our forum, we approach neurodiversity through so many different perspectives right? As a neuroscientist from your point of view, Yewande. And as just a curious thinker. As a mother, Jen, from your point of view through a disability justice lens, through an ADHD lens because I think something that is really important to name is that neurodiversity and being neurodivergent encompasses a wide umbrella. Whether you are BPD, whether you are ADHD, whether you're autistic, or if you don't even want to go into specific labels and you just think you know, actually I'm neurodivergent, I'm going to embrace that. And Yewande as you wrote in issue 3 that it's about acceptance and accommodation and I think that's such a clear summary of what it means to be neurodivergent. Because it's something that you choose. If you resonate with it, then it resonates with you. You don't have to prove it. You don't have to explain it to people. I think about it a lot like being queer. You don't have to explain your queerness. It's an umbrella term and if that's what resonates with you, it resonates with you. Queerness is fluid by nature inherently. So I think being neurodivergent is inherently flexible and accommodating and accepting of wherever you are and however your brain is working that day. Because we can't predict right? Especially for ADHD babes, we don't know how our focus will be that day. Or any other people who are autistic who are listening or reading. You don't know what your sensory needs will be that day. But what has been kind of y’all's introduction into the language, like what got you curious about this language and this movement?

Yewande

For me, it was a friend who I met through this artist collective. So I like to dabble in science and the art space as well and I had proposed an assembly, it’s this convening where over several weeks you have a topic and people come together to kind of be nerdy. And we had to pitch them and they had pitched a neuroscience project and it was around neurodiversity but the language I wasn't familiar with at the time. And then like a year later they reached out to me and told me about this zine that they had put together about being neurodivergent and what are my perspectives from a neuroscience perspective. And then we just ended up having this ongoing conversation where we would meet weekly and sort of just delve into it and it really just evolved from sort of this quite narrow lens I think to this much wider lens which is one of the things that I think is so important about neurodiversity. It's really about widening the lens of difference especially when you're coming to it from the understanding of the brain that the way that we study the brain typically means that you take 1 group of animals or people that behave in a similar way and you compare it to a group that's not…It's actually not the difference, it's more that it's wrong or abnormal or this is abnormal and that is what allows you to understand what's normal. So in having this conversation I really understood the language a lot more and then as you say Jezz, one of the things that's so great about neurodiversity that I value is that there is a distance from diagnosis which I think is really loaded because diagnosis can often imply some sort of deficit or malady and really it's more about identifying a difference. And I like identifying rather than diagnosis. So I've begun to understand I don't think it's easy to grasp initially. But once you do begin to sort of get into these conversations, you realize that it's not really about the definitions, it's more about the feeling and the acceptance and whether it resonates with you and adopting that language and then adding to it. It's kind of like improv you know, it means this and. Because it's about your lived experience. So I really appreciate having that opportunity to actually explore this.

Jezz

Yes I love that it’s this invitation into and then you get to adapt according to your experiences and we talk about this in another episode. It's about understanding that it's the feeling and the practice of it. The practice of access, the practice of accommodating, the practice of acceptance. Jen, what was your introduction into this language and also because you're such a leader, a leading voice in disability justice and you introduce a lot of people to disability justice practitioners and theories and thought forms. What do you see as the connections between neurodiversity and disability justice?

Jen

Yeah I think that the beautiful connection is the intersectionality that's very much rooted in making sure that folks have access to resources, that mutual aid is a space where people feel safe to get those resources. And as Yewande was saying, diagnoses always tends to put a hierarchical aspect on disability and it's like okay, well we know that diagnoses aren't always accessible and we often know that people with privilege, people with health insurance, people with elements of accessible health care are privy to those different types of diagnoses. And sometimes late folks who get identified later on as being neurodivergent, they don't necessarily have access to those types of diagnoses. Or it's just because they've spent an entire lifetime masking or their behaviors look a little bit different and so therefore identifying as neurodivergent may look a little bit different for them in terms of what clinicians or doctors are consistently looking for. And I feel like with disability justice, the aspect that is so empowering is the community aspect and when you're not necessarily privileged in getting a diagnoses to get that access to care, medication, or therapy you can rely on your community. You can rely on your comrades to make sure that you have the access that you need and that's really what I feel that disability justice really represents. It really represents the collective care aspect to feel liberated in that collective liberation. And making sure that there's not a hierarchy in terms of disability in the way that “well your disability is better than mine” or “you don't have a physical disability so you don't necessarily understand the voice of a neurodivergent person.” It’s: we have needs, we have access needs, we have care needs and let's collectively get together to address those needs to support each other and to me that is how I got introduced to the language of neurodiversity and disability justice, leaning very much on the non-medical model of disability, the non charity model of disability and wanting to follow what other actual autistic and actual disabled folks were uplifting and what they were preaching. So like the teachings of Lydia Brown who runs the autistic women and nonbinary network and their ability to galvanize autistic acceptance in terms of what they teach and what they practice and what they're consistently uplifting in the community especially on an activist level. And Alice Wong with Disability Visibility, being able to make room for disability and disabled voices to make sure that they have the freedom to say, to express, to write what they feel is their true definition of their lived experience of their disabilities and so anyone within the community who made room, those were the folks that I was like wow like, it's not just about them, they're actually uplifting others within the community and I felt like those are people that I can get behind. Those are folks that I can easily feel represent what disability justice really means.

Jezz

Oh yes, I love that summary. It kind of has me thinking about how, as I've become more radicalized, and I use that word the way Angela Davis has described— radical as of the root. What radical just means is we're returning to the roots of things and really returning to the root of why oppression exists, why hierarchy exists, why power is abused. And I think that is the root of so many of my curiosities: how does power work? Because I'm so curious about relationships and how we can be in better relationship with ourselves, the land, and each other and in my quest of that constant digging of that knowledge, I think that took me to racial equity, of course studying the Black Lives Matter movement, studying the #MeToo movement, gender equity, divesting from gender binaries, and then that took me into when I first saw the book like the title Care Work by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, I thought wait…care work? I think that's what I've been doing. I've just been caring a lot because I care a lot about the state of the world and about how to practice more care. I'm so curious about how do we create a culture of care? And the more that I dig into that question then I just come across like deeper deeper deeper and what we learn so much from organizers and on-the-ground activists in all forms is: we center the voices who have been the least protected and the most oppressed and when we do that, then we lift everyone up. And I think in America and probably around the world too but in America, specifically that's Black, queer, trans, disabled people. People who exist within all those intersections have had the least amount of protections and so when we center those voices, and really people of color too in general including Asian, Latinx, Indigenous people. So when we center those voices and we listen to those voices and we let those voices lead, then we’re covering so much ground and understanding how we can truly create a sustainable movement for liberation. A liberation movement that really takes into consideration— also feelings, right? I think we talked about this in the forum in that I think I had shared a lot in my earlier days of working in the intersections of change and movement work, I thought so much about sacrifice and trauma. I really focused on trauma and doing something that a lot of people do which is trauma bonding, which I don't think is inherently negative in any way, I think a lot of the times that's some of the most accessible language that we have to connect with each other, by venting. And sometimes we're in situations where we have to complain and vent to get things out and find other people who are experiencing similar struggles and find solutions together and strategize solutions together. But I did that for a while and then I found that the toll it took on my body was just kind of really heavy. And it made me feel like well, what am I working towards and what am I working for and so that's when I started to incorporate a lot more manifesting and visualization techniques and somatic healing practices and thinking, how can I bond based on shared visions. And I think that's what we did in the forum and that's what we're doing now too. What is the vision that we have of the world? What if— thought experiment— what if we were living in a world where everyone was familiar with the concept of neurodiversity and applied that to their work, to their friendships, to their lovers. Imagine that. So I want to pose that question and let's dream out loud. What would that be like and what would that look like, what would that feel like, what would that be like?

Yewande

Do you want to go, Jen? I'm still processing what you said Jezz. I remember that part of the conversation. There's so many things that you both said where I was just like, wow. But I remember when you were describing the trauma bonding and that process and how important it is but this idea of visioning and thinking about what we would like it to look like. I've been thinking about that a lot, kind of going back to what I've been thinking about recently, which is the safety of that community, Jen you're describing so beautifully how disability justice has been so pivotal and intersectionality as well and when you do find those spaces. It's amazing. But what happens when you go out into the cold metaphorically speaking and how do you receive the care and give the care that you deserve and want to receive without having to individualize as well. I think being neurodivergent is a personal choice and when you feel like that's riskier necessarily and don’t want to disclose that so I have been reflecting a lot on how you create environments where it isn't individualized so it's not necessarily just about accommodating you as an individual. I don't have to go into a workplace and say okay the way that the system is built isn't conducive to the way that my brain processes things differently and I need these things which is of course absolutely valid. But how do we get to a place where all of that is considered and it's not about the individual, it's just about a generally more inclusive way of accommodating or not having those assumptions and those barriers to begin with. And how can we widen that land that we were sort of talking about earlier for neurodiversity so that it has further reach. So it's not necessary just in these relatively small environments but in a more general environment. So I don't know if I have an answer, that's definitely something I envision. How can I walk into a space and just feel like I don't have to necessarily advocate for it and it can be just something that's assumed.

Jezz

I love that your answer is a question though because I think of this quote, this disabled academic scholar Josh A. Halstead I believe I read it in Extra Bold: an inclusive anti-racist accessible guide to design. Yes, Jen is holding up the cover now! It's red with pink and yellow design. Extra Bold: a feminist inclusive anti-racist non-binary field guide for graphic designers. If you are in the world of creativity, design, highly highly highly highly recommend. But the quote is “the questions we ask become the stars we follow.” So I love that. I think sometimes it's that. It's just posing questions. But Jen, what about you? What are you thinking?

Jen

Well, you know, definitely everything that you both said and just adding to holding spaces accountable, holding those corporations, big huge spaces, as soon as 2020 hit, Black lives and disabled folks…obviously for decades we had been oppressed and institutionalized and fighting for our rights and for our bodies because it's about survival for us. But those types of spaces were very much othering disabled folks, folks with different disabilities, neurodivergent folks. They were othering us but like you said, the spaces were very uninviting because we weren't necessarily taught how to advocate for ourselves. There was no space and it always felt burdensome and asking for any types of accommodations felt like oh here we go we have to spend more money, we have to make more room for this type of person who needs these types of access needs and then when the pandemic hit, we ended up realizing that all of these accommodations that disabled folks had been advocating for to have within their reach was finally put. It ended up becoming this very universal thing where everyone's like yeah, we could have class online every day and still be somewhat successful. We can give rides to the polls or we could actually have folks mail in their ballots and during the election it was all of these things that we had been advocating for, continued access finally came to light as if they were discovered for the first time. When in essence, disabled folks had been showing up for each other in these ways for so long. And we still are. So when you're talking about dreaming out loud it's continuing to hold spaces accountable, continuing to let folks know that disabled voices have always known how to work with very limited resources. So why don't you give us that opportunity to actually build that table instead of giving us just a seat at the table. Let us build it. Work and build alongside us. Don't build the table for us or around us. No, let us actually build it ourselves. And just giving us more tools, more resources. And again one of the principles of disability justice is leadership of the most impacted, letting the folks who are most impacted by their disability, most impacted by oppression, the lack of accommodations, let us build those spaces. And that's something that Josh [Halstead] really talks about a lot too. And his work when it comes to divulging, looking for those answers within architecture, looking for those answers within museum spaces and Shannon Finnegan's work and calling out the lack of access in different museum spaces that are meant to in essence free people through art and creativity yet museums are the most inaccessible spaces at times because we're expected to stand for long extended periods of time to ingest the work and there might be like one bench there where we're expected to suck in all of this beauty but yet we're uncomfortable, our back is hurting. We're just not necessarily feeling like we're being accommodated for or seen within spaces of liberation, spaces within art practice. So yeah, just again holding more spaces accountable, allowing for people to to allow for us to actually plan what those accommodations can look like so therefore they will already be set in place. And there's really no excuse. I mean there are so many spaces now, Pivot Diversity that's run by my good friend John Marble based out in San Francisco. Dr. Haley Moss, there's so many folks that do neurodiversity in the workplace chats and forums and panels where we can again, continue to hold these corporate corporate spaces accountable.

Jezz

Jen, what you're saying brings up the idea for me that access elevates the creative process and a lot of people I think who aren't familiar with the beauty of disabled creativity, disabled wisdom, disabled lineage and thought do think of access as a burden. Let's be real, like you said, “oh we have to spend more money,” “oh we have to do this, we have to make it part of the process, “oh we have to redesign the website.” Well, if that's already part of the process in the beginning, if you're already working with disabled people, if you're already considering neurodivergent experiences from the beginning, then the output just becomes that much more amazing. It also reminds me of the project that you designed with I believe Alice Wong and someone else created the Society of Disabled Oracles which you can find at societyofdisabledoracles.com, right?

Jen

Yeah, with Dr. Aimi Hamraie from Vanderbilt University, amazing author and human, also autistic. I feel again, in referencing Alice, it's about creating an opportunity for folks, specifically disabled individuals, to express as you had mentioned their disability wisdom, their crip wisdom, their ability to to warn folks, to hold space for freedom but then also for danger and making sure that we're all safe within our own communities so what would that look like if we had a space where we can share those warning signs, we can share those words of light, those words of freedom. Leaning on each other's wisdom but in a very honorable way. Honoring our ancestors, honoring folks who may not even exist yet, but folks trying to uplift within ourselves. We're still evolving and we still haven't even evolved into our full selves until we continue to be more honest and more true and more authentic with our bodies, I still feel like there's so much more within us. And that's what the Society of Disabled Oracles is really helping to hold space for, and it’s really beautiful being able to use creativity and design to create these telegrams where folks can literally go on a website and or just fill out a Google Form and they're asked questions specifically about what are some of the ways that you're able to keep your disabled community and your friends and yourself out of danger? How are you able to spread that wisdom in terms of what people don't know and what they have yet to discover about their own disabled lives and body minds? And yeah, it's just beautiful to be able to hold space for all of that wisdom.

Jezz

Mmm, yes. Creating avenues for mutual aid.

Jen

Yes.

Yewande

Yeah, thanks so much Jen. Everything that you just said and referenced really resonates. Just thinking about being that at conception and inception and the design and having this from the beginning, these considerations, but then also what you said about advocating within the workplace and making space to then create that when it hasn't happened from the beginning. I wonder how universal that can be. I think in design or creative spaces, but also within the medical industrial complex or in other industries, what that could look like and when I had said before not individualizing it. So it's something that is already in place, I guess you do need pioneers or people to begin. And so the organizations that you reference was really inspiring just to think about how even though we might social communities where we have those sort of safe or braver spaces you can find that within these wider kind of areas where maybe it doesn't look like it exists and finding common ground with people and then starting small and building those out and borrowing that kind of approach from other areas, I found really inspiring.

Jezz

Yes, because all this work of questioning culture and questioning norms is liberation work. Because liberation work is so much about understanding why we do the things we do, why things are structured the way that they are, and who it's actually supporting. Who benefits from this? Who does it harm? Who does it help? I want to quote something that Yewande, you wrote in issue 3 about how, “whenever we associate a person's ability to function with their inherent worth, we run the risk of finding ourselves perpetuating father of eugenics Francis Galton's idealized fantastical construction of what it means to be a useful human.” And you say, “if it is society that makes some people unable to function, then achieving equity would require a great deal of unlearning.” And if I'm drawing these imaginary thought bubbles of equity, design, neurodiversity, it’s really questioning, what are we valuing and why? I think so much of the medical industrial complex is like, do this so that you can be more productive and so that you can look more normal so that you can be more accepted within this dominant society, dominant workplace norm, or what is just considered polite. There's the language of respectability politics that a lot of people of color talk about. So it's all connected and it's this beautiful web and lineage of wisdom, of change, of transformation, and it also in the end empowers us— you know, Deem is so much about designing an equitable world, right? And design as a social practice. I think so much of that in terms of lifestyle design too. I study a lot of, what does it mean to design a liberated lifestyle? What does it mean to design a lifestyle around my needs, around the values of ease, enjoyment, satisfaction? What a radical thought for anyone who exists within any margins to say, actually I want to live a beautiful and joyful life. Because there are so many systemic barriers to that. So to even dream that is very radical and then to practice it, because all of this is, again, a practice. Yeah, I'll pause there and see if any thoughts come up for ya'll.

Jen

Yeah, I just wanted to hold space for Lois Curtis who recently passed on, who is an amazing historical figure in the disability community. She's a disabled ancestor who passed away on November the 3rd. And in terms of how you're speaking in terms of creating this life that's very much rooted in access and care and joy. We disabled folks, especially neurodivergent folks, really wouldn't be here without being able to understand what she did, living as a neurodivergent woman, a disabled woman who literally fought against the institutionalization of disabled folks as that often being the very first space where a lot of folks feel like “crazy people.” “The non-normal people where the invalids belong.” It’s like, if you don't live the way that society deems as ”normal” then you don't necessarily belong in this society, we have to put you in a space where you can roam and be with those other people who, as you said, are “less than,” because we're not necessarily considered human. And so Lois Curtis in her 70s, she was a part of winning a huge landmark case specifically to uplift the civil rights of disabled folks so that we could literally live where we want, where we could be independent, where we don't necessarily have to be subject to the institutionalization of oppressing our minds, our bodies, but holding space so that we can live freely and live that lifestyle that you're talking about, but for it to be respected. And Lois [Curtis] actually created a lot of beautiful artwork and paintings that were very joyful and full of glee and very simple that really emulated her spirit, her childlike self, and so I just keep thinking of those folks that really help to pave the way for what you're saying, for that ability to even speak in that way like designing a lifestyle of liberation, of acceptance. Because there's still many of us who can't really even speak to those terms, especially when our mental illnesses and mental disabilities and when I say illness I mean illness in terms of ableist society. That's what I really feel like the illness stems from, the lack of respect, the lack of humanity that we're consistently shown contributes so much to that “illness” that we have to live day in and day out with, because of how we're not uplifted. And someone could easily respond to what you said as, well what are they talking about, living a lifestyle of freedom and respect? Well you know, I'm already doing that because I have like a hundred shoes and I have my house in the Hamptons and there are certain things and material things that people really apply to that specific lifestyle. But really, we're just talking about being respected for just existing as neurodivergent, that’s really what we want to be respected for.

Yewande

Yeah, and just to add to that. The irony is that actually in nature, and I think we often separate ourselves from nature as humans, “it doesn't apply to us” but the fundamental basis of nature thriving is diversity. So it's kind of crazy how it's framed in these binaries where you have normal and therefore abnormal or differences are then bucketed into, rather than just differences, like better or worse, when it's just difference. And all that neurotypical really means is that a group of people's brains process the information in a similar way compared to other brains. But actually thinking about neuroscience and understanding how the brain works, the more we understand those differences, the more we create room to explore them rather than just thinking about it through the medical model lens. The more we just understand how our brains work, full stop, and we understand ourselves and our humanity, and I think you mentioned before Jen that dehumanization and the othering, I think that the irony because it just helps us to understand ourselves as one whole, even if we have these differences, but it's the full scale of the infinite variability in the human existence that allows us to see our full capacity.

Jezz

I love that, that allows us to see our full capacity. And now I'm even thinking, we started off this conversation initially thinking the framing of it was the science of neurodiversity. But really I think what we're getting to the root of is the possibility of neurodiversity, what does neurodiversity make possible and even in thinking, I'm a neuroscience nerd too. So you talk about neuroplasticity. You've talked about it before, Yewande, and neuroplasticity is this idea that you can change the shape and composition of your brain based on the way that you use it. Based on the information that you consume, the thoughts that you think. It's a big healing tool for me as someone who has experienced childhood trauma, as someone who has experienced chronic depression, anxiety and ADHD and I'm autistic too. So there's all of these ways that I feel like the world as it is is not built for me and then there's compounding impacts of that and then physiological responses to that and everything. But I really see neuroplasticity as this possibility of, wait I determine how my brain works, I determine the language that I use to describe myself, I determine the future that I want. And I think about that as— what kind of world do I want to build? Sometimes I think of my body as a world, I think of my community like my direct, my closest friends and the people that I see on a regular basis, that as a world. I think of the city that I live in as a world. The borders are made up, borders are social constructs. But I think of the countries that we live in as worlds and all of these worlds colliding and changing shape with each other and it’s also an act of art making, to be able to shape your brain. That is sculpting, that is architecture, that is an act of creation. So I think that's what I'm rooting myself in now. Neurodiversity to me sounds like a possibility generating machine, a possibility generating mindset.

Yewande

Yeah I completely agree with you. I love how you've reframed the conversation and thanks for that because I love how we've ended up in this now because that's really what I think we are talking about and all of that possibility through it exploring, you mentioned neuroplasticity earlier Jen, I think well maybe it was you Jezz, about masking and late diagnoses and how maybe neurodiversity presents differently in different folks because they've had to adapt that adaptability which is magic. That's what's amazing about our brain. So even the masking is indicative of neuroplasticity and how we just adapt. So yeah, I love that you kind of summarized it that way.

Jen

Yeah, I brought that up earlier when you were talking about trying to individualize diagnoses and how oftentimes because folks don't have a diagnosis, they don't necessarily feel like they can disclose or even consider themselves as being neurodivergent but like you said, and I mentioned this earlier where we've had to experience our lives especially as women and folks who identify as women, dealing with those different aspects of masking and adaptability and how that can change the whole elasticity of our brain because it changes our speech and our tone and the way that we codeswitch. We have to show up in so many different spaces as so many different versions of us and yes that is an art form, that it is a science. To be able to do that and have the power and the means and the capability to do that. And imagine what that looks like as a person of color, which we all are, and how that in itself could be a space that is empowering but then also a space where it's oppressive when we have to live like that 24 hours a day without the privilege of a diagnosis because we don't have access to medication or to specific therapies or if we don't disclose. Some people don't disclose, therefore they don't know that there are communities out there for them. For myself, before I was comfortable disclosing, I felt very isolated, I felt very alone. And then it really took for me to actually raise a child as someone who we had to get a diagnosis because of what the school system was saying that we needed to do in order for the child to be accepted, in order for the child to be productive. And then I started to say, wait a second I'm seeing reflections of myself through my kid. I think we're the same. I think we're cut from the same cloth, obviously, but my behaviors are different then as he's continuing to grow, I'm thinking well, I did those same things. I had those same stims, and I had those same subtle eccentric behaviors that were very joyful and whimsical and full of life and that literally made me into the person that I am today. Like social butterfly and also very eccentric. And those aren't hindrances. Those aren't aspects of our personalities that should be stifled. So yeah, it's definitely a very interesting conversation in terms of the way that we regenerate these essences of ourselves and the way that our brain completely functions. And I feel like if we allow ourselves to continue to be authentic, obviously there's a shift, right? There's a social shift. There's a medical shift. And for me, I felt like the more comfortable that I’ve become disclosing, celebrating different aspects of neurodiversity and allowing for folks to usher in, helping to organize folks to do that same kind of celebratory talk about themselves, I feel more liberated. And we talked about that a lot during this conversation, being free. We're in the business of freeing people, right? We're in the business of collectively caring for folks. It's heart work, it's care work for us. And that has to shift, right? That has to shift the way that our heart beats, the way that our skin glows. It has to shift so many different molecules within our body minds. As long as we remember to take care of ourselves. That’s where it can get a little tricky.

Jezz

Yes. Ah. Disability is not a deficit, it's a difference. I remind myself that all the time if anyone listening or reading needs a mantra. I will write that on post-it notes and I'll remember it because yeah it can be dangerous sometimes disclosing and it can be scary for people who feel new to this and who might not have community to talk about this with, to use this language for themselves. But it is so freeing, speaking from personal experience. It's freeing and then it helps me to then advocate to, as you say, shift the cultural perception which then ultimately can shift those interpersonal perceptions too. So we're gonna wrap up this beautiful and illuminating conversation with 2 final questions. And this first one I've been asking everyone. What is some language you use to advocate for yourself? This could be in either professional or personal settings.

Yewande

It's a good question. I can go first. It's still a work in progress. So I think language is so powerful and can be empowering once you figure it out. So I don't know if, I’m not using any specific language to advocate for myself yet. But I have been thinking a lot about how I talk about myself from a neurodivergent perspective. So when you go on the NHS, the National Health Service in the UK and you read the description of ADHD traits in adults, thinking about the conversation we've just had, it's really jarring to see how loaded and judgmental the language is for something that's meant to be a medical definition. And it is so loaded and I'm not going to go over them because I don't think we need to in this space but just trying to find ways to describe the same things without those value judgments and then if I am going to use a value judgment, making sure it's positive. So, for example, an inability to deal with stress is one of the descriptions. It’s not an “inability.” There are so many other ways that you can describe your relationship with stress or “poor organizational skills.” Why is it not “I have a particular way of organizing that requires a little more time and care.” So just challenging myself a little bit because I think even before exploring neurodiversity, I had language for myself that was inherently judgmental like I'm always late or I'm so forgetful, I lose everything. These kind of judgment descriptions and so now I'm just trying to be more mindful about the way I describe things and making sure that I'm not internalizing language that isn't helpful until I find language that I feel I’m comfortable with.

Jen

I love that, I love that so much. Exactly.

Yewande

It’s a fun game, like how do I say…

Jen

It's very much like “a lack of attention to detail.” I'm just reading some things.

Yewande

Right? It’s such a long list, I'm not going to bum us out by reading all of these things. But yes.

Jen

Ah, lack of attention to detail, difficulty sustaining attention, poor organization skills, easily distracted. So when I look at those words and when I'm trying to kind of translate them into words that I feel like can best uplift those things about myself, I just think of authenticity, transparency, and anti ableist. And that's what I tell my students, I'm coming to you in a space of radical softness, meaning that, and that’s something we talked about earlier, as loaded as we are with where our brains don't turn off and when we're diving into and galvanizing all these communities and in a sense that's a space of being radical, but we're also soft. We're also sensitive. We're also very much in a space of care where we actually make time to care for ourselves and just holding space for this conversation to me is an act of care. Because we could easily be bogged down in a meeting or doing something else but I feel like convening and being in community is a safe space and that's what I tell my students or folks that I'm working with in terms of consulting or workshops or having fun making zines and I'll tell people: I'm coming to you today in radical softness, like as my full authentic self and full transparency, disclosing my access needs. So I'll start off all my presentations and this is something that I just started doing in 2021. I'll have a slide that introduces myself and then the next slide will literally be “I have ADHD” and these are my access needs. And even though you normally characterize ADHD with these traits, just know that I'm super sociable, I love making friends, I love collaborating. These are all of the things that are great about my ADHD and that make my world a livable space and a space where it's okay, you can be my friend, I'm not just going to…sure, I may cut you off once I'm bored or something because I struggle with that kind of thing. But if you're still meant to be in my life but we're not co-creating or co-collaborating, if I still love you, you're going to be there. But just know that I'll be able to read you more quickly if you just want to be my friend because you want something from me versus you just want to be my friend so that we can be friends. Like I'm able to very much read into that. I can read the aura because I spent most of my life trying to hide that about myself, trying to not be super expressive super intuitive. But now I'm like, no I need to be able to be comfortable identifying those types of things because this is my safety. I don't want to be taken advantage of, I don't want to be used, I want to be uplifted. Because oftentimes with ADHD, we're sensitive. We're trying to people please and we're trying to be the yes people but no, we have to be so much more mindful of what that means for ourselves and we have to care for ourselves. But that really comes from a place of authenticity and transparency and I know that was a lot, but yeah.

Jezz

I mean speaking of reframing language, I know sensitive has different connotations to different people. So if someone is thinking, I don't want to use that term to advocate for myself, you can use: attuned, aware, intuitive and those have different connotations in different spaces but that is not something to be ashamed of at all. Well, the final question that maybe we can just answer in a few words or sentences is: What do you want the future to feel like? We've talked about this kind of the whole episode but to summarize, what do you want the future to feel like?

Jen

I just want it to feel safe. You know, like I said, I feel like I want it to be a safe space where we could all just be ourselves and survive because I have to be honest as a Black Latina woman who has a disability, literally this is a survival game for me. And it's a safety game. I just want to be safe to continue to take care of myself, my family, of my child who is at risk as a Black autistic boy who's gonna grow into a Black autistic man. I just want a safe world for him. And to me, the future will not be secure unless it's a safe space where he can be completely free.

Yewande

Yeah, I agree Jen. I just jotted down 2 things and I had put: how to create safe and brave spaces with wider parameters. So all of these amazing groups, the disability justice space, design a space that Deem has created, just a blending of those so that it is like these boundless parameters of or no parameters of acceptance and then the other was in the meantime, how to be and create safe and brave spaces like how do you just carry that with you wherever you go? Yeah, those were the two I thought of.

Jezz

I love love love love that. I'll leave that with people. How do we embody this conversation, the lessons and learnings from this, and put it into practice in our everyday lives and relationships? Thank you so much Jen and Yewande for your energy and your wisdom and information. Can you share with people where we can find you and how we can continue to support you?

Yewande

Yeah, absolutely. You can find me on Instagram it's @nyewro. I do science communication work so I share the projects that I am working on and collaborating on there. One of my biggest passions is making science more accessible and especially these conversations about intersectionality. I really want to make that the focus for me based on my own experiences and the experiences I'm learning from others. And then my website as well, that's linked in the Instagram so I'll just share that.

Jen

Yay science! Make science more accessible. And this is Jen, you can find me at Instagram as well @jtknoxroxs and also I'm online at jenwhitejonson.com. And you'll see lots of posters and stickers and zines that are all uplifting autistic joy and ADHD and disability visibility and holding space for the language of design justice and disability justice through art. And continuing to give the world the art that I don't necessarily see a lot of. Again, it's a very small space that the disability community exists in and yet we know how to take up so much space. But I feel like if folks aren't necessarily sharing what we do and uplifting what we do, then folks will act like we don't exist our perspectives, our communities, our pedagogies will be constantly erased. So I'm really in the business of sharing and bringing joy and and celebrating all of those disability narratives through a design justice lens. So yes, follow my work and thank you, thank you.

Jezz

Thanks for tuning into Dreaming Different, hosted by Jezz Chung for Deem Journal’s Audio Series. If there’s anything in this episode that resonated with you, we invite you to be a part of our exploration in collective dreaming by sharing Dreaming Different with people you know and leaving a review on any podcast platform. Reviews are immensely helpful for our reach and impact. Also as a neurodivergent tip, I find that I process information more deeply when I listen or read something for a second time after I’ve had some time to digest it. Sometimes I even listen on 1.5 or 2x speed and that feels really good for my brain. Sharing those tips in case they can support you in processing all of this delicious information.

Big thanks to the entire team at Deem: Alexis Aceves Garcia, Jun Lin, Jorge Vallecillos, Alice Grandoit-Sutka, Isabel Flower, Nu Goteh, Jorge Porras, and Amy Mae Garrett for their contributions to the ideation and production of this series. Special thank you to Nu Goh-teh for composing the dreamy music you hear throughout the series. It took so many conversations, iterations, and practices of spaciousness to bring Dreaming Different to you and we hope it helps expand your ideas of the future, the world, and the possibilities we can create together.

If you’re new to Dreaming Different, we recommend checking out the introductory episode, which lays out the origins of this series, what we intend to explore throughout the episodes, and my personal journey with the neurodiversity paradigm. Episode 1 also includes some somatic and mindfulness tools to use if you feel any discomfort or tension while listening.

You can find the complete series including transcripts and show notes at deemjournal.com/audio and Deem Journal on Instagram at @deemjournal. I’m Jezz Chung, you can find me @jezzchung across social media, and I hope you do something to take care of yourself today and all the days ahead.

Thank you for dreaming with me.

Show Notes

Jen White-Johnson

Yewande Pearse

Lydia Brown

Autistic Women and Nonbinary Network

Alice Wong and the Disability Visibility Project

https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/about/

Care Work by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

bookshop.org/p/books/care-work-dreaming-disability-justice-leah-lakshmi-piepzna-samarasinha/16603798

Extra Bold: A Feminist, Inclusive, Anti-Racist, Nonbinary Field Guide for Graphic Designers

10 Principles of Disability Justice

www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/10-principles-of-disability-justice

Shannon Finnegan

Pivot Diversity

www.pivotdiversity.com/neurodiversity

Haley Moss

Society of Disabled Oracles

www.societyofdisabledoracles.com

Lois Curtis

https://womenshistory.si.edu/stories/how-artist-lois-curtis-won-disability-rights