New Forms of Articulation: Sumayya Vally in conversation with Esther Choi

Photography by Anita Israel & Manuela Barczewski

Sumayya Vally photographed by Anita Israel.

I was told by a wise person, several years ago, that people are akin to tuning forks. Like the sound of a piano or an object falling to the floor, we are vibrational beings and emit frequencies that extend outwards. I first met Sumayya Vally when I approached her earlier this year to lead a session of my virtual programming series, Office Hours, on the topic of starting an architecture practice.

It became clear in our first meeting that Sumayya radiates a particular energy, not only in terms of the strength of her political beliefs, but also through her ability to imagine, with confidence, what the future could become. Yet amidst her conviction, she is honest about the difficulties in charting new paths for worldmaking that can heal and repair, as much as they can innovate. In our conversations, she has taught me not to be restrained by the fear that comes with recognizing one’s power and responsibility, which might otherwise deter one’s next step: We make our paths by walking.

ESTHER CHOI: Now that your 2021 Serpentine Pavilion commission has been up and open for a few months, how are you feeling?

SUMAYYA VALLY: It is a gift to imagine something and to see it being realized, even more of a gift to see it being lived, and to be a part of working with its life. We convene in buildings and we are convened by building—the act of making this pavilion has been and is a coming together and a growing gathering of so many voices,past, present, future. I am honored that it’s not mine anymore, that it belongs to the world. That’s a really beautiful feeling and is, for me, the best part of being an architect. There is this moment, when it isn’t yours—it’s in the world.

Having said that, when the Pavilion opened, I realized that the work had not ended, but that its true start had begun; it has catalyzed so much work around it. I also collaborated with Natalia Grabowska (the Pavilion curator) and our Pavilion fragment partners and custodians on several events across the summer and beyond. This process of carving and sharing platforms is really at the heart of the project and hopefully it will continue beyond it too.

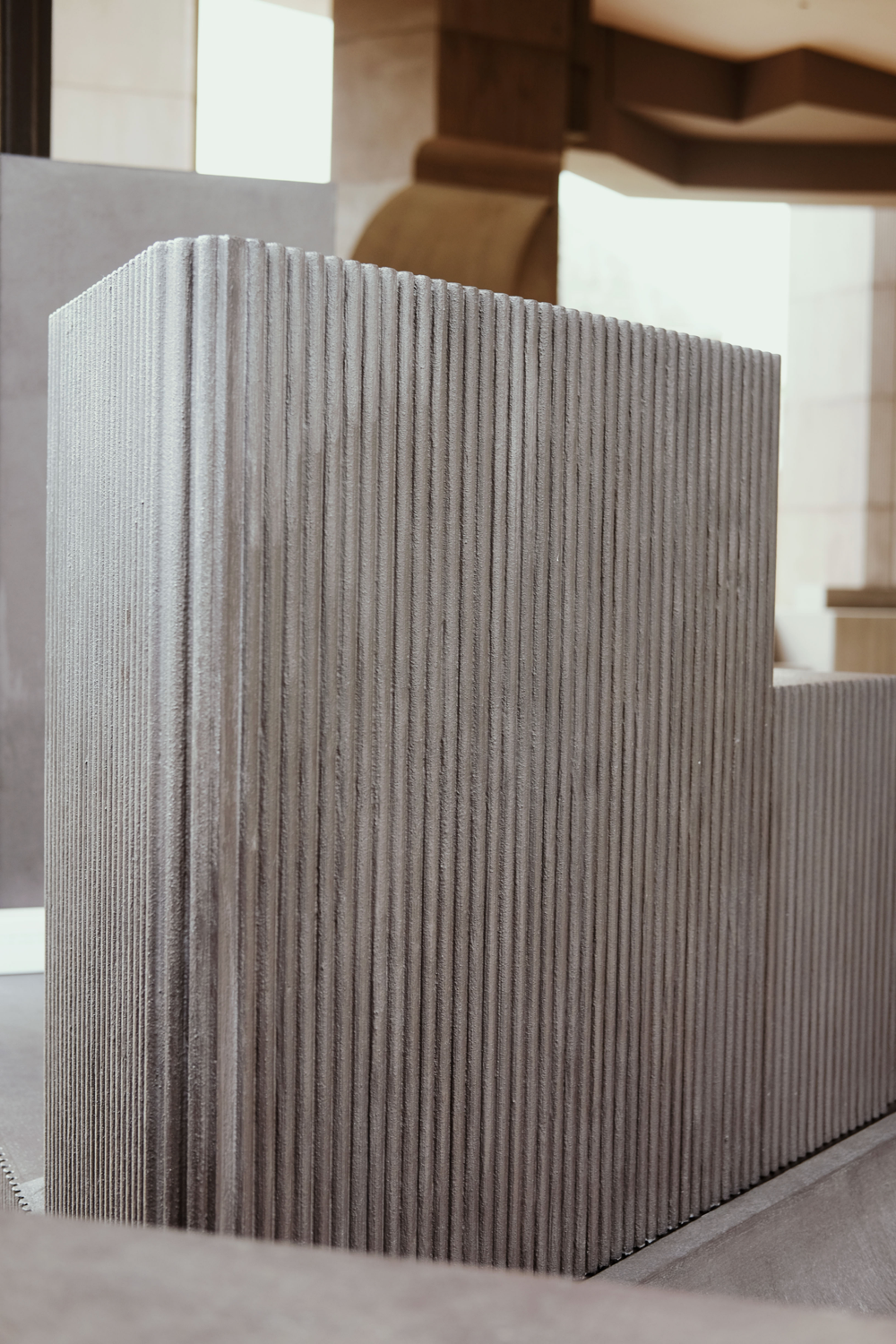

Serpentine Pavilion 2021 designed by Counterspace. Photography by Anita Israel.

EC: I love the pictures of people hanging out on and around the structure. I wish I could be there to experience it in person. Have you been able to observe how people are interacting with it?

SV: It’s wonderful because, of course, I designed it to be very interactive. Unlike some of the previous pavilions, there’s no furniture put into this one. It’s designed so that it functions as furniture and it was inspired by architectural gestures of generosity. In many other places, I saw the ways that interaction is facilitated—whether on neighbourhood porch steps of Brixton before the time of protest, through sound system architectures, or through an unfolded surface for a fast break in the street around the time of the Grenfell protests. I strived to embody and imbue those moments by bringing their spirit of generosity into the pavilion. To see people actually using it in this way is profound and I hope that all of these voices that have meant so much to the structure are honored.

When I first arrived and finished quarantining, I had to take a COVID test and then be quite careful to avoid going onto the site for an additional ten days because it was really important to protect the construction team. As soon as it was legal for me to leave my apartment, I went straight to Hyde Park of course, and spent time observing what people were saying about the structure, because it went quite high above the hoarding. Once I had developed this habit, I did that every single day, and I had a great mix of observations.

For example, one group of students was really excited to learn the pavilion was by a practice from Johannesburg, and they started to break down why they think we are called Counterspace. There was this incredible moment where one of them asked, “I wonder what it means, ‘Counterspace?’” and the other said, “Duh. It means counter spaces. Different spaces. Spaces for us.” It was such an honoring moment for me to know that people, in our generation, are really feeling that, and that it means something to someone—that was wonderful. Then, soon after, an older man on a bicycle walked up to the structure, saw me looking at it and said, “You know, a summer pavilion is supposed to be really light and this one looks like a monument. I don’t know what’s going on in here.” I said, “Yeah, I wonder what the architect is thinking.” I spent a lot of time in the Pavilion, watching kids climb over it, people spend time reading or listening or finding intimate corners for conversation. It’s been an incredible gift to be present and a part of that.

Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 1999), 125.

EC: I’m reading a book titled Decolonizing Methodologies by Linda Tuhiwai Smith that was recommended by Chris Cornelius (studio: indigenous). There’s a line I came across that made me think of you, and in particular of a conversation you had with Hans Ulrich Obrist that was broadcast last year. It reads, “Research is also regarded as being the domain of experts who have advanced educational qualifications and have access to highly specialized languages and skills.” The book critically examines the top-down set up of how knowledge can be extractive and often at the expense of others. I think a lot about how architecture is taught in schools, and more often than not knowledge production is taught as a form of imperialism and extractive tourism. The “master architect” executes a plan for social reform based on a research process that replicates the same hierarchies of society and a centralization of decision-making power.

When you described your research process for your project to Obrist, you spoke about the importance of looking at a variety of “non-traditional” archives, engaging in conversations, and going on site visits to understand lived experience. I thought it was interesting that the pavilion cites many architectural forms designed for different types of civic address for assembly by non-architects. In some ways, the pavilion operates as a composite portrait of multiple publics, temporalities, histories, and so forth —or what you refer to as a diasporic way of thinking about subjectivity as an aggregate. Your research privileged knowledge that wasn’t professionalized and the project sought to pay tribute to this knowledge.

SV: Absolutely.

EC: It seems you placed yourself in a position of learning and dialogue, as opposed to a position of expertise. How do you picture your role in this set up, which is in some ways ethnographic but is also self-aware about what it means to enter a social situation and try to understand various communities?

SV: Thank you so much. That’s beautifully framed and absolutely at the heart of what I’m working towards, because what you observed was also my experience of architecture education, the university system, and bureaucracy. I’m very aware of this because I was always told “No. No, this is not architecture. No, this has no place in architectural discourse.”

Until even a few years ago (even though things have shifted a lot since then), people were saying, “You can’t talk about race and gender in architecture.” I know that’s still happening but it’s become much more subtle. I was told very directly that the work I was trying to do didn’t fit into the discipline or the canon.

“The desire to think about other forms of archive, and other ways of holding knowledge, has always been embedded in my work, whether that’s in a lived space, whether it’s in land. Land is also an archive. Dust. Recipes. Songs and stories.”

I’ve always felt this frustration that there’s a misalignment between what I’m seeing and what I’m inspired by, in every way—pragmatic, aesthetic and conceptual. I’m inspired by rituals, whether economic or spiritual, that have richness, where there’s a lot of material to delve into, learn from, and experience. I felt that somehow my work didn’t fit the form of the “professional” or the “archival” or the systems that we have. I am interested in forms and systems that exist in our context that are actually far ahead of the systems of archiving that we’ve been conditioned into. And thinking about things that are digital is often so interesting because there’s alignment within what is hybrid, shifting, evolving, and mutating. Or that are ritual, oral, aural, to something that is digital or sonic. The desire to think about other forms of archive, and other ways of holding knowledge, has always been embedded in my work, whether that’s in a lived space, whether it’s in land. Land is also an archive. Dust. Recipes. Songs and stories. There are so many instances in South Africa of superstition and gossip, of myth and legend that have turned out to be important for holding stories of people and places, and that have also been found to lead to archaeological finds, historical evidence, etc.

In one project I was working on, there was an unmarked cemetery of 3,000 indentured Chinese laborers that had recently been found on the mine dump and was not documented anywhere previously. I’m not advocating for some kind of “post-truths” society, but I do think that being able to see the validity in other bodies of knowledge, and the ways that some bodies of knowledge are privileged, is important. We often do not think of the mystical, the mythical, the embodied, the performed, the oral, or the ritual as solid bodies of knowledge. We look at them with a lesser hold than we do things that sit in formal archival structures. But, understanding that all of these things are intertwined and that there are ways of honoring bodies of knowledge that don’t fit into the archive has always been important. This project tries to draw on that concept, and on archives that exist within physical spaces and through experiences—the sonic pieces in the Pavilion and through the programming of the Fragments.

EC: I’m really interested in the idea that your work can activate embodied and sensory conditions, which, in architecture, have always been interpreted through the philosophical lens of phenomenology—an impulse that tries to create a universal and humanistic model of subjectivity. Because sense perception is framed as non-linguistic in phenomenology, it presumes that understanding the world through our sensory perceptions can somehow be generalized into a singular or homogenous experience. Yet your work takes that discourse to a much more politicized level by recognizing that sensory conditions and affects are culturally encoded, specific to particular contexts and ways of relating, and, therefore, highly variable.

SV: Absolutely. They are a form of language. I was thinking about how in every language, the dog bark sound is expressed differently. In English you say, “Woof, woof.” In some Asian languages, they say, “Mong, mong.” To think that to someone’s ear, depending on their geography, but also their tongue, that sound is completely different, also tells you that from that worldview, perspective generally is completely different. Of course, to a degree, we’re all hybrid. From a cultural perspective, there are so many lenses involved in how we articulate. Let’s think about a very simple architectural example—perspective—which we inherited largely from the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods, and which privileges the individual. A single perspective has a foreground and a background, foreshortening, a directional axis and so on.

However, in an Oriental take on perspective—Japanese or Persian for example—there’s much less of a privileging of any one body; instead, lots of things are happening in parallel and within the same plane. If we think of these compositional styles in relation to worldviews, I think these are also cultures that are able to hold many different truths or many different ways of being—occurring at the same time.

That’s one example of how cultural specificities are embodied in drawing language. Drawing language then manifests and in turn influences culture.We need to understand this power of what we do to continue, seed, or evolve cultural conditions; and, when we start to make something, we need to be aware of what legacy it is sitting in and taking on. There are, of course, hundreds and hundreds of others, and many have not even been translated into design representation because of colonization, apartheid, etc.

Of course, as an architect, I believe there’s power in working in plans, sections, elevation, and axo. We can create light, shadow, and draw atmospheres into being from things that are orthogonal. But that needs to be supplemented with other languages, too, because in many other ways of being, space-making is not limited to the static. There’s so much that can be created without much physical infrastructure. Think of the many African ways of being—from ritual, dress, adornment, and sound. Yet this dominant Western narrative has taught us that ornamentation is a crime and that such forms of expression, or otherwise, have no place in architecture. So, even though I still work within certain conventions, I also very much believe in supplementing with and privileging other modes of representation, because I think our forms of articulation are limited—we can only see and think through what’s possible with the language we have to articulate it. Once we expand on that language, we can produce entirely different worlds.

Think of film, which is centered on perspective. Take Akira Kurosawa’s films for example. The way that color is used. The way flatness and atmosphere are created. The effect is completely different, and I think draws very much on those Oriental perspectives and on the way that parallel plans are created at the same time, whereas predominant ways of filmmaking for many regions in the North-West, whichever way we orientate, utilize sequencing that is linear and that embodies a form of time and atmosphere that we subscribe to in our neoliberal, capitalistic world.

EC: Do you find that you’re able to instill these ideas that you’re working through in your teaching? I find this can cause real tension between divesting from colonialism within one’s mental universe and the colonial parameters of the world as it is. As an educator, I often feel pressure from university administrators to stay within the structure of the Eurocentric, male canon despite institutional claims to support decolonial and emancipatory pedagogies. Have you been able to integrate the viewpoints that you’re trying to privilege in your own practice within your pedagogy?

SV: There’s definitely tension, but I’ve been lucky to teach a master’s course and that’s really freed me up. I worked under Professor Lesley Lokko, within the system she created, which is geared towards and around imagining from a different perspective. I had that support from the very beginning of my teaching career. I didn’t have the burden of having to teach the canon, as it’s graduate level, but there also was an assumption that everyone already knew the canon and this is about something that’s different. And, though I do think there are elements within the canon that we can learn from and draw on, I actually feel borderline offended when people tell me that they can see Western references in my work, as well as African, Indian, etc., because, of course, that is an embodiment of who I am as a human being, English is my mother tongue. I speak in our colonizer’s tongue better than in my mother’s. That is a reflection of the fact that we are all hybrid and we can draw on and learn from many different sources. The issue arises when we pretend that certain sources don’t exist. For too long, only one specific kind of canon has been permitted to develop and evolve at the expense of so many others.

“Our forms of articulation are limited—we can only see and think through what’s possible with the language we have to articulate it. Once we expand on that language, we can produce entirely different worlds.”

EC: I never aspired to be a university administrator, even when I was tenured and encouraged to apply to the position of an assistant dean. These days, however, I find myself gravitating towards a fantasy scenario of imagining new frameworks for knowledge production in the form of a para-academic institute and questioning how one would completely redesign an equity-based, intersectional pedagogical experience for students and educators. How we might cultivate a fertile place for a very different approach to practicing and thinking about worldmaking that centers non-violence, in its myriad forms, at its core.

SV: This is something that I think about all the time. Again, I was lucky to work in a school that was very open to new but we also had to learn and develop within the bureaucracy of the broader institution. Lesley Lokko has now started an independent school called the African Futures Institute, which is largely driven by the fact that institutional structures can’t hold what they need to hold in order to take this project further. At the moment, what is really required is flexibility. It’s a two-part project. The first part is about having the space to imagine a curriculum differently—through allowing for multiple forms of representation while expanding our vocabularies and definitions of architecture to include many, many other things. Of course, my students work in many different media and everything is spatial, but this work doesn’t always translate into a physical building. It might translate to a festival, or a set of choreographies, or creating a set of architectural costumes, or a dictionary of architectural terms. The other part is about starting to find and work through systems that can make those things possible, because the systems that we have at the moment are really limited. For me, Serpentine’s fellowship program Support Structures is also a project that came about because I was thinking about the role of the public institution in the city—what it has the power to give rise to, and what it should be giving rise to.

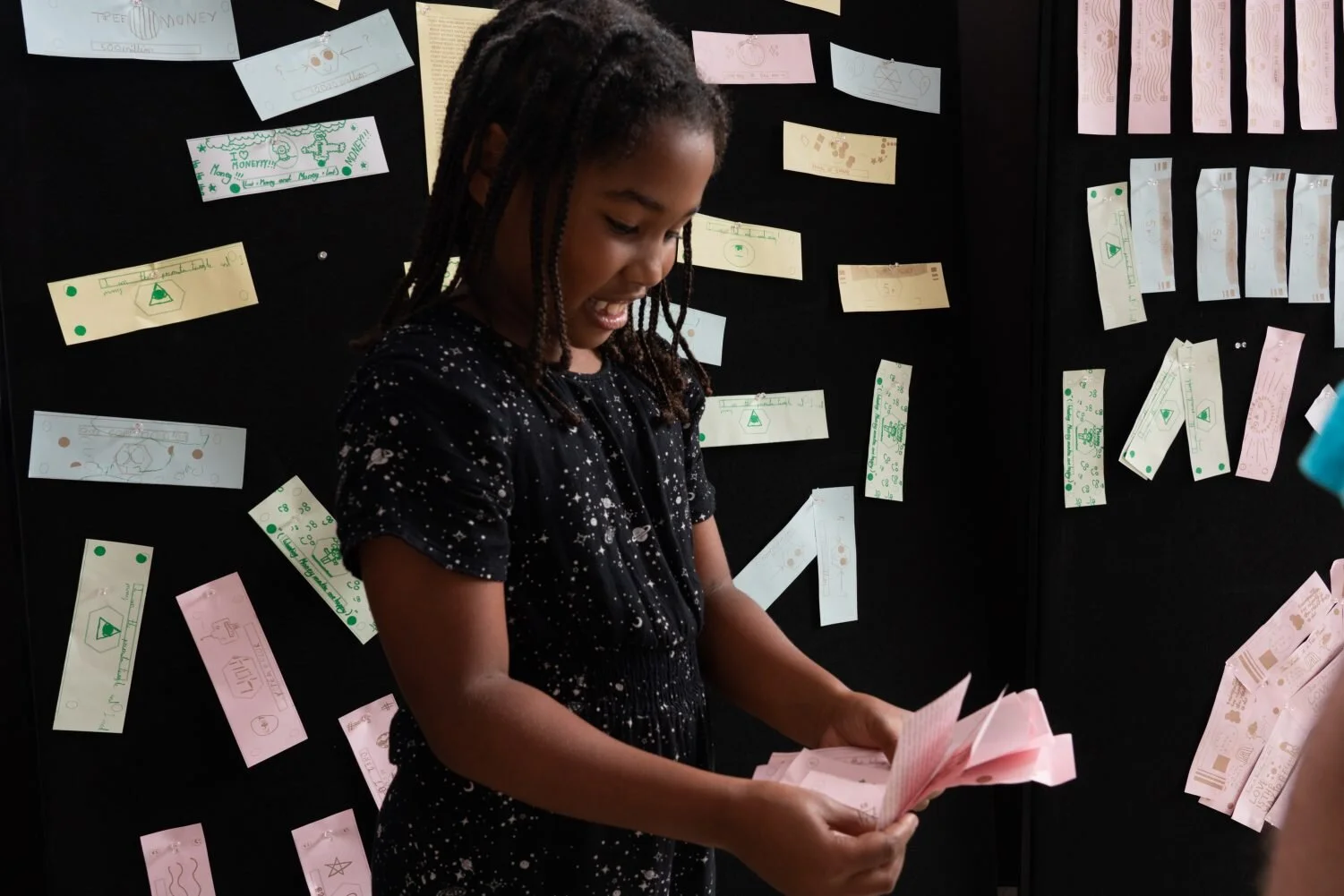

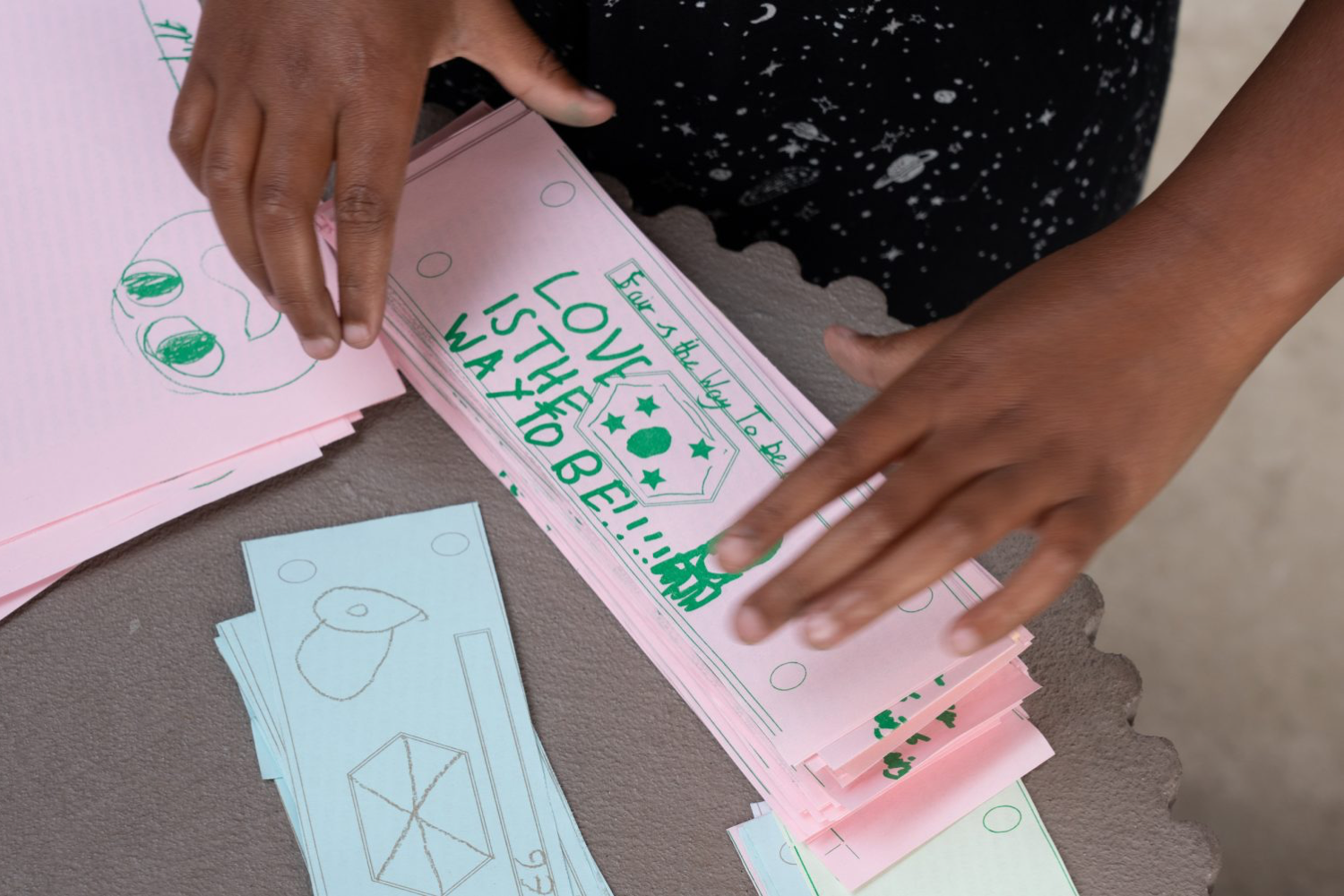

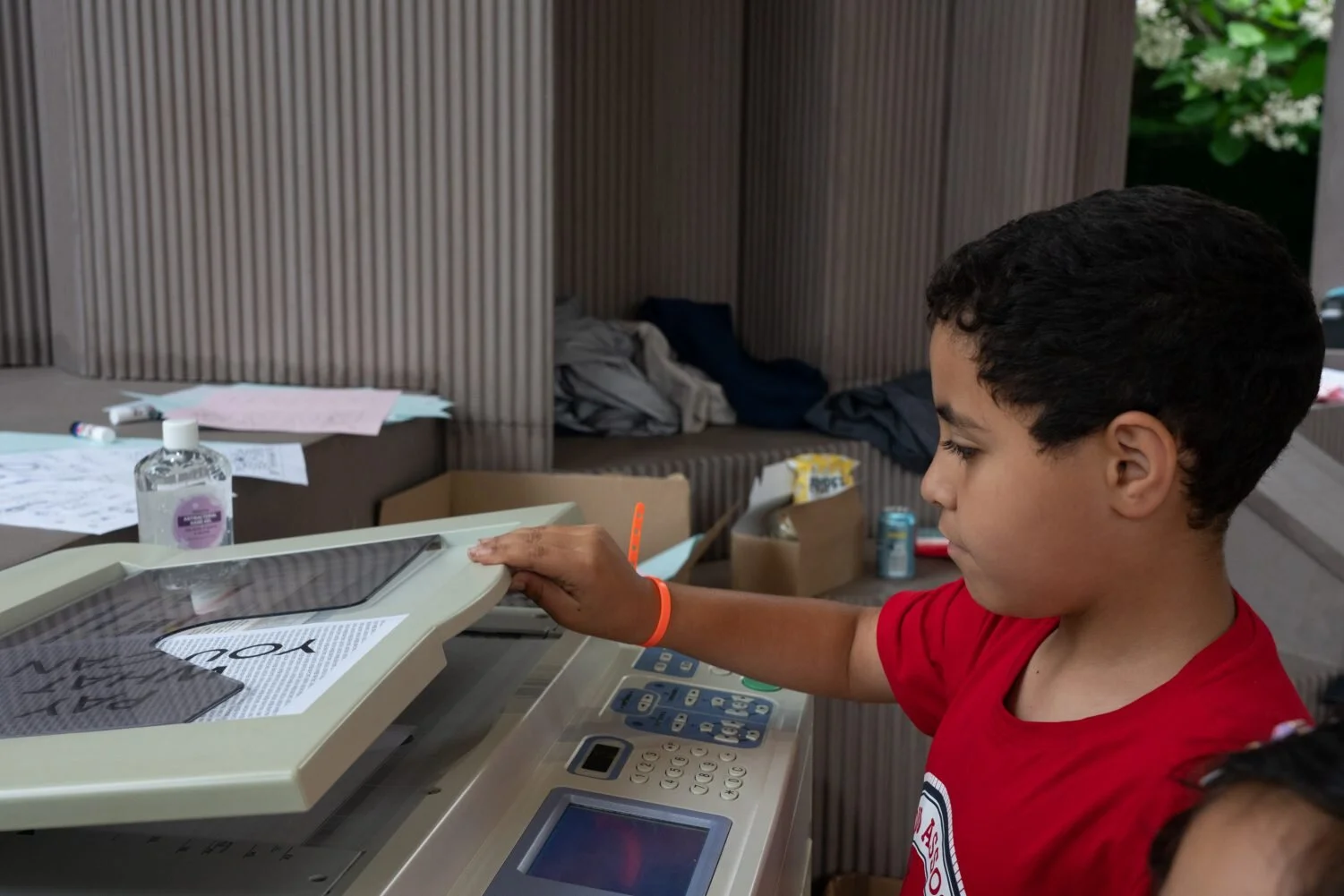

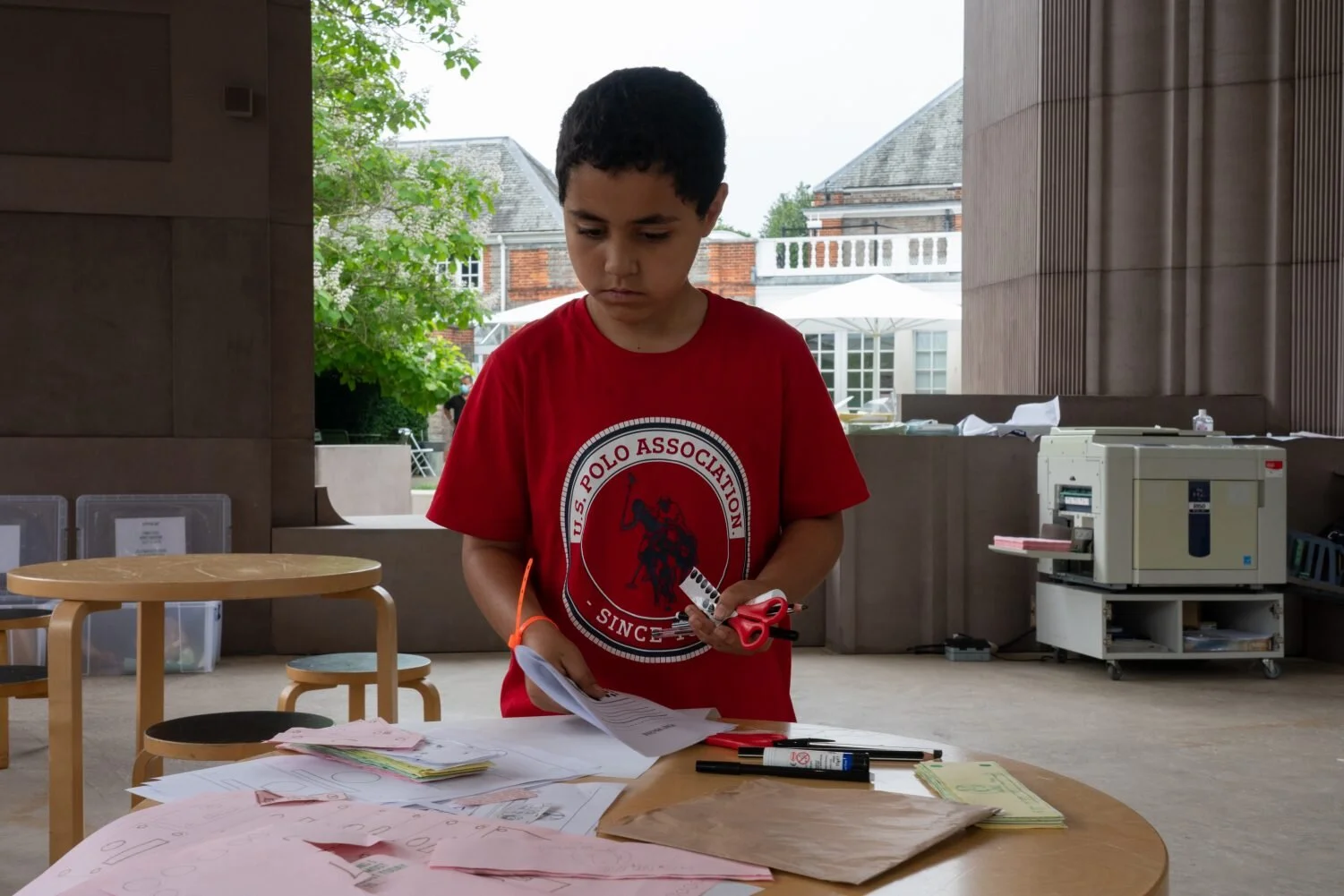

For One of My Kind (OOMK)’s summer workshop “Family Day: Money Machine,” children and their families were invited to design and print their own currency in the Serpentine Pavilion. Photograph: Manuela Barczewski.

EC: I was just on Instagram this morning and saw a post from Jonathan Jackson (@WeShouldDoItAll) about the surplus of black squares on social media around this time last year, yet how, beyond the signaling of one’s virtue, there’s actually been very little change, structural or otherwise. How can we measure transformation, and how do we keep it going? It’s easy to get discouraged when it seems things are defaulting to the status quo.

SV: I’m absolutely optimistic. I think the situation that we’re all in is dire, but I’ve also seen a lot of shifts. I was born a few days after Nelson Mandela was released, into this whirlwind of change. Of course, there's still such a long way to go, but one must remember that the changes that have occurred seemed impossible for so long and for so many people. We have to realize and understand that we’re standing on the shoulders of many; we’re standing on the shoulders of Mandela, of Malcolm X, of James Baldwin, of Martin Luther King, of Miriam Makeba, of Simon Nkoli, of Winnie Mandela, Graça Machel, of Toni Morrison, of Maya Angelou, of Bell Hooks, of Steve Biko—these are small moments in a very long history. And though change is never enough, or fast enough, it is happening, slowly. Even earlier in this conversation I mentioned things that were said to me when I was a student that would be totally unacceptable now. Maybe these interactions would still happen, or would be cloaked differently, but they would be much harder for someone to get away with.

I think ours is a very optimistic project because we have so many worlds to imagine from our various perspectives, and we also access many levels of privilege. We’re educated. We have access to platforms. We have to think about what that privilege can do and how it can serve something different. But I think we’re doing that—at the very least, we’re trying. What else can we do but be optimistic? Joy, imagination, and beauty—also forms of representation—are deeply political tools to express difference and to present alternative worlds.

EC: In my everyday life, it has taken a while for me to meaningfully understand how to best use my resources and skills to actively counter forms of domination. It is an ongoing process. The project of decentering whiteness and heteropatriarchy is as much about unlearning, as it is about reinvention. None of us are infallible to causing harm, while we are also so vulnerable to being harmed because of our identities in this world. But you’re right: Optimism is what keeps us going. What other choice do we have?

In the past few years, I have adopted a real sense of urgency around re-envisioning the commissioning systems by which we can create new spaces that would enable different voices and conversations to take place, and to pay it forward. Yet, when I think about how to gain access to the capital that enables that to happen, when I try to justify the acquisition and redistribution of that capital, which is itself so racialized and generated through inequality, that’s where I find myself feeling stuck.

SV: Working with platforms and resources that we have access to, in the service of projects of difference, is an opportunity to imagine the world differently. Creating platforms that function in entirely different ways through these avenues is an opportunity. The intent with Support Structures is that, year after year, it will build and grow a deeper network of bodies of knowledge that are coming from places of difference, so that we can seed and see different pathways and other worlds.