MOLD Magazine’s LinYee Yuan on design and the food crisis

As told to Deem

Photography by Guarionex Rodriguez Jr.

I'm a design journalist and for the past decade I’ve been writing primarily about industrial design. As an editor for the industrial design website Core77, I attended design festivals around the world. In 2011, I started seeing really interesting projects, usually by students, that addressed or confronted different facets of our experiences around food including growing, packaging, transporting, storing, selling, and eating food.

At that time, it felt like the design media was really focused on things like lighting and furniture, and food media had no interest in covering design projects that dealt with food. There was a singular focus on aesthetics and product with no real concern with systems. I felt this was the gap I wanted to address.

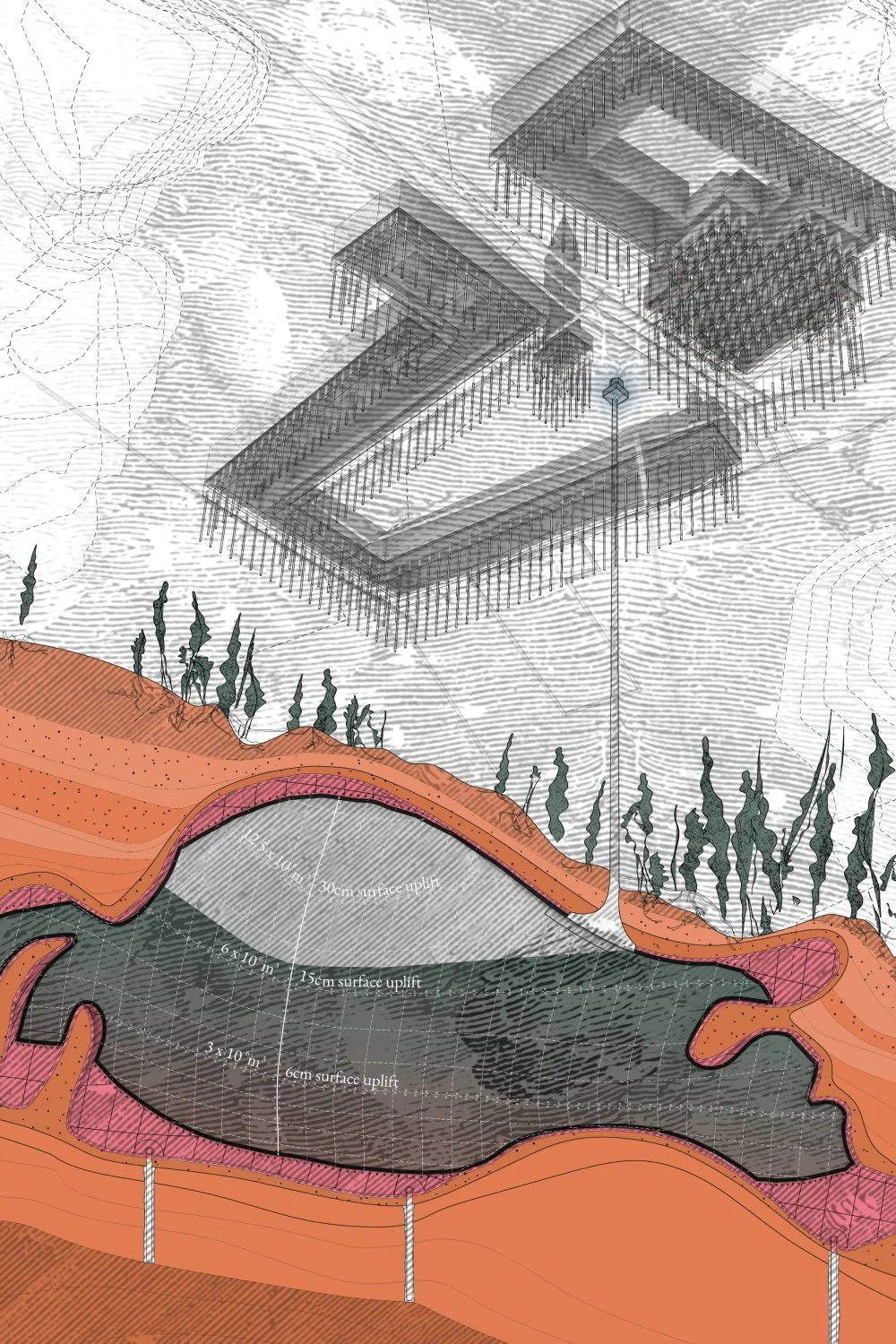

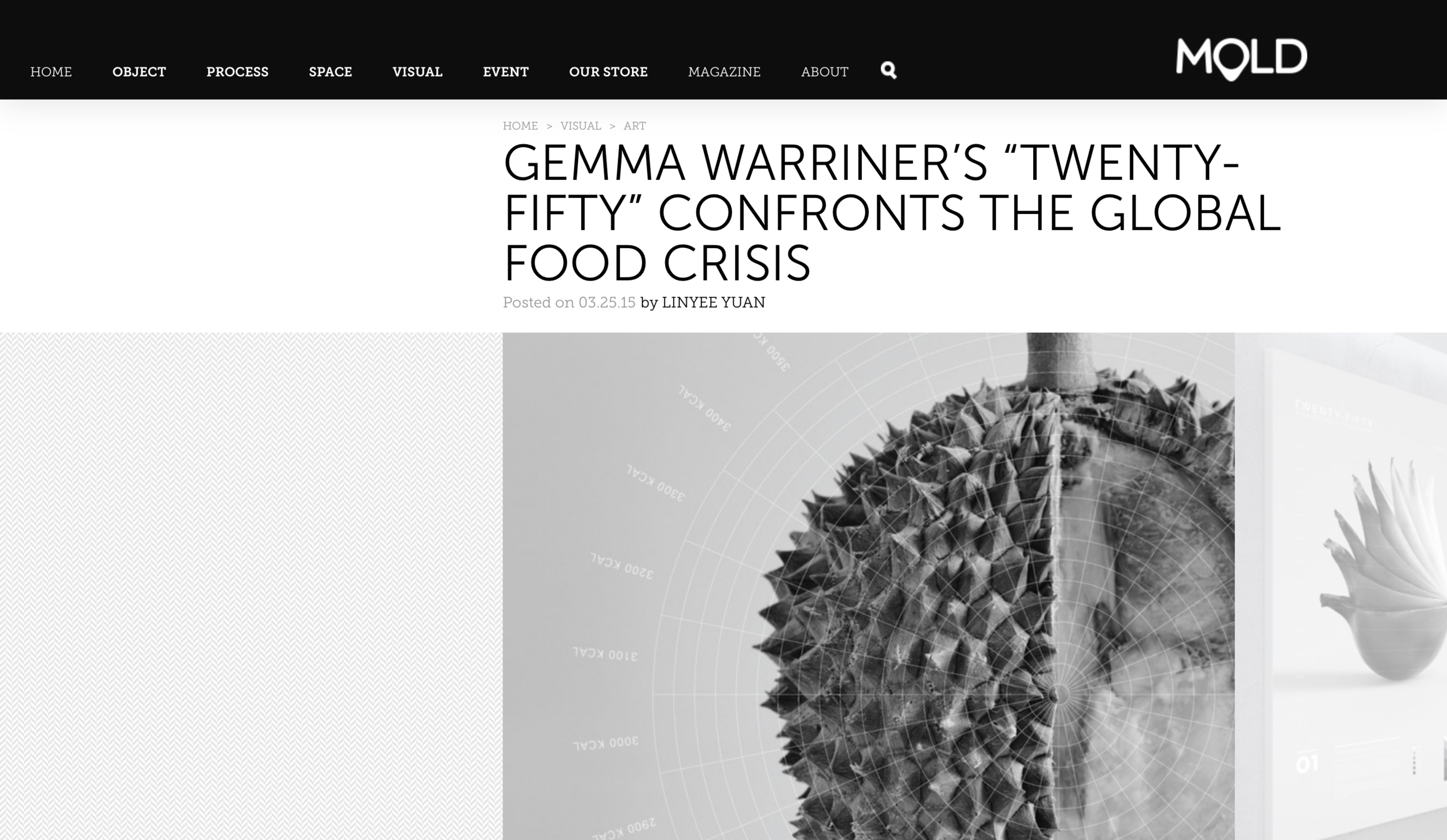

In 2015 I wrote about a communication design project by a student in Australia that used photographs of produce to illustrate details and statistics around the coming food crisis. The United Nations had issued a report warning that if we continue to eat and drink the way that we do, by the year 2050, when there are over 9 billion people populating this planet, we will not be able to produce enough food to feed everyone. That idea completely terrified me. This particular student project told the story in a way that was accessible to a more general audience. I found this to be very inspiring.

I started MOLD in 2013 as a platform about food design—and after being confronted by the reality of the food crisis, we focused on how design can address the food crisis and shape the future of food.

“How can we harness the joy and play that are very human and very much part of our food experience as vehicles for creating, providing, and imbibing in a way that is nutritious, delicious, and fits holistically into a regenerative food system?”

I love the process of making a magazine, which is partially why I chose this format. There’s no way for a single person to make a magazine. It’s a collaborative endeavor that requires cooperation between people with different skills, different voices, and different ways of seeing. The current popular interest in independent magazines is a testament to the fact that people still want to have a tactile, immersive, slow media experience. That’s very gratifying for me, as somebody who makes an independent design publication with no advertising that has both integrity and a point of view.

To me, design is a process that offers solutions through a very specific lens. Design is also a profession; it’s a practice. I think it’s important that design have a seat at the table to offer key tactics to solve the critical questions of today. I believe that designers are trained to work in an interdisciplinary way, which as we know, is essential for figuring out how we can address complex issues. This is in part because designers are trained to frame the right question. Instead of settling with “Here’s the question that is being asked of me," designers must determine, “What is the real question we’re trying to answer?” This kind of analysis is enabled by understanding systems. Design must consider how things work within an overall context, while also taking into account certain constraints.

“I think it’s important that design have a seat at the table to offer key tactics to solve the critical questions of today.”

— LinYee Yuan

Designers are taught to think at scale, especially industrial designers. It’s relatively easy to say, “I'm going to make a widget that will solve X problem” but what about “I'm going to make this widget. It will be but one way of solving X problem. What will make it effective are ease of scalability and affordable price point.” Recently, I was at a conference with farmers, engineers, and designers and we were talking about the tools we need to empower small-scale farmers to farm in a way that is efficient but also intimate with the land. One of the most powerful points that came out of that conference was how important it is to create tools that are modular and accessible. Modularity is also something that I think designers are uniquely positioned to consider.

How can design ask questions and offer solutions that fit into people’s daily lives? This seems to be the key to chipping away at huge issues, such as how we will feed ourselves in the future. How can we harness the joy and play that are very human and very much part of our food experience as vehicles for creating, providing, and imbibing in a way that is nutritious, delicious, and fits holistically into a regenerative food system? Though our solutions should be human-centric, we must think beyond just feeding ourselves; how can we also confront the ills of our food system that are environmental, economic, and geographic?

“When we talk about the food crisis, it’s not necessarily a crisis of culture.”

I am the child of immigrants but I was born in the United States and grew up in Houston, Texas. I am a first-generation Asian American woman. I think that, like many first-generation Americans, much of my sense of identity and belonging revolves around eating experiences. My family loves to cook and really came together around food. My mom is a dietician so I’ve always had a healthy relationship with food. My father is an engineer, an avid gardener, and a passionate fisherman. As a result, my family always had a direct relationship with understanding where certain foods came from. This is not to say that we didn’t go grocery shopping, but even our purchases were specific to particular kinds of stores and cultural contexts. This meant going across town once a week to buy groceries at the Chinese supermarket, or going to the Mexican grocery store in a totally different neighborhood to buy tortillas or a specific spice. Eating and sourcing food always had a relational context.

When we talk about the food crisis, it’s not necessarily a crisis of culture. We’re talking about our physical ability to produce enough calories to feed over 9 billion people in just thirty years. What we are really talking about is our ability, as a species, to cohabitate the planet. MOLD’s editorial platform is interested in all the specificities of how design can have a hand in offering solutions for this. In particular, how can design help create regenerative and resilient food systems, because at this point, even sustainability is not enough. We’re in an ecological crisis; the products and solutions we create need to do more.

“We need more transparency and we need more biodiversity. That means that we need to think about systems, not just about the linear progression from production to consumption.”

An example of a regenerative solution might be evolving the current system of industrial agriculture to replenish soil by pulling carbon out of the air and putting it back in the earth through specific agricultural practices that consider the interconnectedness of soil health, microbial health, plant/animal health and human health. A resilient solution might mean reviving certain seed breeding and planting practices that encourage diversity and hyper local ecologies. We need more transparency and we need more biodiversity. That means that we need to think about systems, not just about the linear progression from production to consumption.

And for the rest of us—people who are shopping at the grocery store and picture ourselves as mere consumers—how can design actually help us become partners in the food system, or creative partners with the food system? The reality is that as consumers, as people who eat, we have enormous agency. How can we start to understand that we all play an active role in determining what comes next? What can design do to aid in this?

“Given the variety of experience and subjectivity, constructing a conversation that will engage as many people as possible in the existential challenge of the food crisis is a huge and complicated design brief.”

The biggest challenge in creating a narrative around the food crisis is that there are so many different ways that people think about and relate to food. For most people, their relationship to food is defined by access, or a lack of access. Given the variety of experience and subjectivity, constructing a conversation that will engage as many people as possible in the existential challenge of the food crisis is a huge and complicated design brief.

People’s relationships to food are often dependent on location and this is a productive entry point for thinking about what’s possible. I live in New York, the largest city in the country, which happens to be located in a particularly fertile region. How can we connect those dots? How does a city of over 8 million people support agriculture that is being produced in support of local ecologies? How do we improve food access? How do we teach our youth about the power of growing their own food? How do we keep money that we spend on food within our communities? How do we buy fish that is being caught with sustainable methods off our own coast? New York is an island, so why are we still insistent on eating tuna? How can we remedy the fact that one of the biggest food distribution points in the country is also located in one of the most food insecure places in the country—Hunts Point in the Bronx. That’s a huge problem, but there are so many small things that can actually make a difference, and I hope that MOLD will be a platform to communicate and spread these ideas.

You can find out more about Mold Magazine at thisismold.com.