adrienne maree brown on creating the future

Interview with Alice Grandoit

Photography by Anjali Pinto

adrienne maree brown at her home in Detroit, Michigan

Renaissance thinker, creator, and author adrienne maree brown is best known for her work in social justice activism and facilitation alongside her ground-breaking books Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds (2017) and Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good (2019). Deem’s Alice Grandoit joined adrienne for a conversation about her journey and her hopes for what’s to come.

Alice: In 2017, you published the now highly acclaimed Emergent Strategy. This book is often described as being about radical self-help: personal help, social help, global help, ecological help. Emergent Strategy has resonated so much for Deem; it has truly been a guide for us in launching this publication. Many people must ask you what emergent strategy is. What do you tell them?

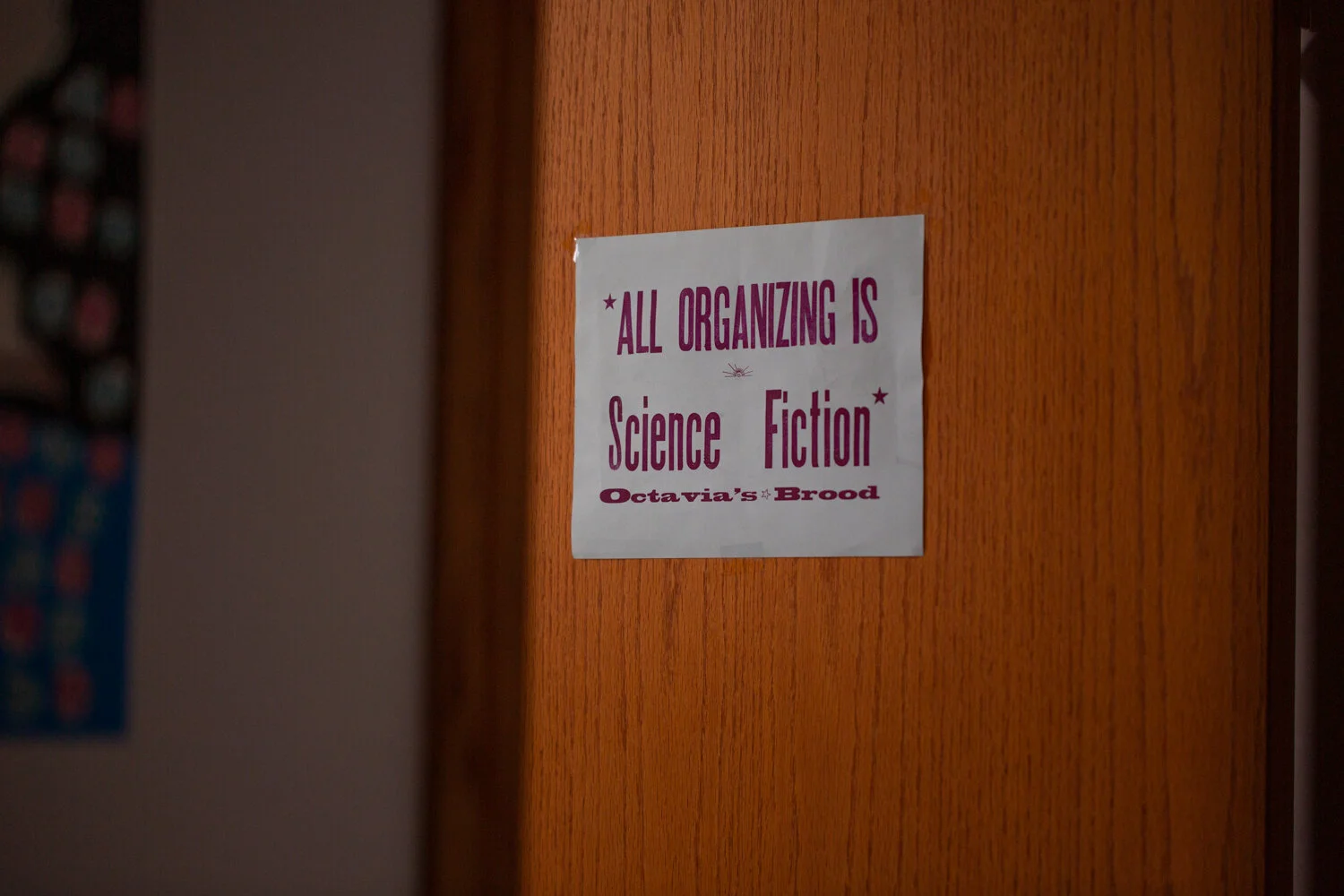

adrienne: My answer has shifted over time. Right now, emergent strategy is how we can intentionally get into the right relationship with the planet and with each other. Emergent strategy is focused towards people who have a desire to change the world. They see that something is wrong. They see that there's injustice, imbalance, and that deep transformation is needed. The question is, how does one transform oneself in order to bring about that transformation? It's also about creating the right relationship to change. So much of emergent strategy is inspired by Octavia Butler and the idea that all that you touch, you change, and all that you touch also changes you back. For most of us who strive to create change, we love that first part—“all that you touch, you change”— yes! But the idea that we're also being changed is much harder for us to contend with. For this reason, the book provides strategies for how to adapt with intention. How can we understand that change is non-linear? How can we understand that change happens through relationships?

I never have a short answer, by the way. You will notice this. A funny thing to me about the book is that I meant to have the introduction be quite concise and the rest of the book be a toolbox. But, as it turned out, the majority of the book is the introduction, and there's only a small toolbox.

AG: You’re a very multi-hyphenated person. What are some of your hyphens, identities, professions, skills?

AMB: Well, the original hyphen, or the original multiple identity, is that I come from a black father and a white mother who fell in love at first sight. They met in a library and my dad made eyes at my mom. They were married three months later and they're still together. They work together and they love each other. So, the first part of my identity is that I am a black, mixed-race woman. I'm also queer, pan-sexual, play-sexual—that’s constantly shifting, too. I'm attracted to magical humans in all forms.

I'm a writer and a facilitator. My facilitation work supports black liberation. And now I'm becoming a teacher too, which isn’t something I’ve really identified as before. Facilitating is very, very different from teaching. Facilitating is about creating a space for people to do something, while teaching is about passing knowledge directly. In my heart, I actually feel like I'm a fiction writer who is dabbling in non-fiction. I mostly write and publish non-fiction even though non-fiction is the hardest for me to read. I'm also auntie extraordinaire. I love being an auntie to many, many nibblings in the world. I sing sometimes and I'm a podcaster. I may be forgetting something, but those are the main things.

AG: How are you navigating the transition into teaching?

AMB: Well, I spent about five years resisting it. Now I'm experimenting and partnering with other people who are helping me understand what it is that I have to offer. We've been doing these emergent strategy immersions. In these spaces I’ve been realizing that the teaching happens when I relinquish my presence in the room. In the first one I was the main presenter. But each time, the other team members are doing more and more. I’m doing some teaching directly to the room, but mostly I'm showing other organizers how you hold this kind of space. I think I'm a good teacher, if I get out of my own way and stop obsessing that I'm going to say the wrong thing.

I'm also very explicit about the fact that a lot of what I do is magic, so it's not useful to try to teach it as if it's not magic. I think for a long time I was trying to do that, like, “Here's how you make an agenda,” but you can't really put magic on an agenda. Instead, one might say, “Here's how you can arrange an agenda so that magic can happen.” Magic happens through relationships and through faith. How do you build the trust so that people believe that magic is possible. You have to let people cultivate solidarity and love for each other, individually; almost anything can happen in a room where people have that level of connection with at least a few others in that space. That's all you need.

AG: Could you tell us about the importance of facilitating social justice movement work in your life? What led you to this?

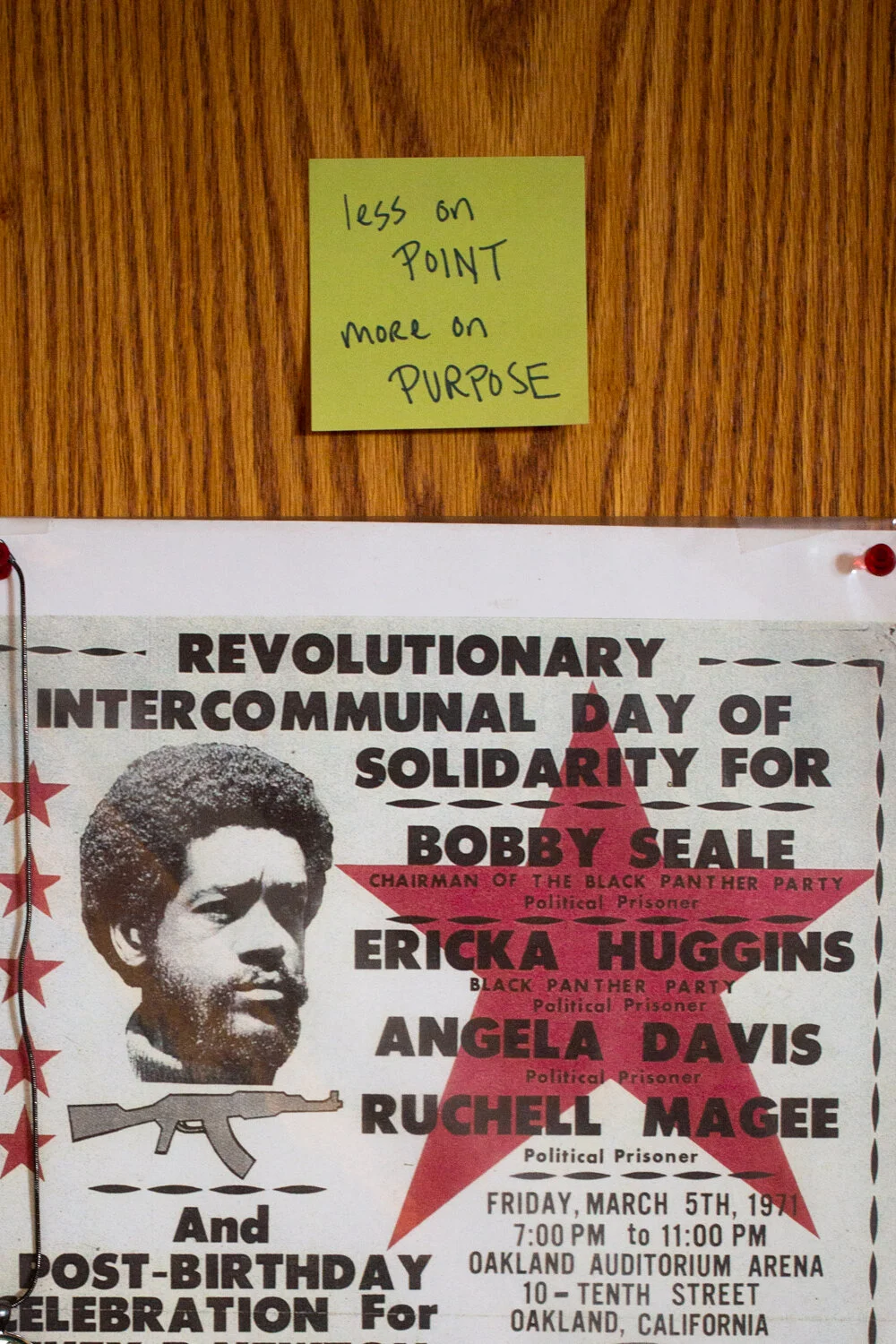

AMB: I feel like we would be much further along in our social justice work if we had more facilitation happening. This has occurred to me many times, especially as someone who was pushed into leadership roles from a very young age. I became a managing director at 23 and an executive director by 26. When I look back, I know for sure that I needed someone to help me have certain conversations in those spaces. I needed people who could help me take a step back and find a new perspective on whatever was happening. Facilitation is exactly that. It's all about making things easier for people. Movement is already so hard.

One of the ideas in Emergent Strategy is that birds coast when they can. Struggle is inevitable, so how can we find places to increase ease? Over the years I've kept sharpening my tools. Now I'm focused on working with black leaders or majority people of color groups, mostly around climate-related problems or issues that are connected to black people, such as police brutality and reparations. Facilitation is passion work for me, so I do it for those who I want to see win

AG: You described Octavia Butler as one of the cornerstones of your awareness in Emergent Strategy. Could you tell us about your introduction to her work and what it means to you to look to her writing for guidance?

AMB: Octavia Butler was a black science fiction writer who did a lot of her writing in Pasadena, California. Before Octavia was born, her mother had four miscarriages, all of male children. Now they've done all these studies about what happens in the womb and how the material of each pregnancy becomes part of the children that come through that space, so I just love this idea that Octavia was at least five people. It makes sense! Her imagination was so vast, and what she could see and how she could understand was so big. She put black women protagonists in direct relationships with the unimaginable. The power dynamics are like, “Wow”—something had to shift so massively. That's the first thing that drew me to her work. A black woman is going to be the first one to talk to aliens and navigate how humans figure that out? Right, that makes sense. Of course we’re going to do that! Or, a black woman is going to be the one who is able to heal her own body just by turning her attention inward and realizing what's wrong. Then she is going to become a dolphin so she can breed a superhuman race of pattern masters? I'm like, "Yes! Octavia, I believe you!"

The texts that are most relevant in this political moment are The Parable of the Sower (1993) and The Parable of the Talents (1998). These two books were written in a trilogy, of which she had created eighty versions. We don’t yet have public access to the third book, The Parable of the Trickster. In these parables, there's a radical right-wing president who runs for office with the slogan “Make America Great Again.” She understood what was coming. She really grasped it. To me, Octavia is a north star and all of her characters are dancing with change, trying to figure out how we can act as guides in processes of change. How do we shape the changes we want?

I want to say one other thing about Octavia. There are more poetic, lyrical writers. She's a very straightforward writer. There's no extra fat on the bone. She’s like: “Here's the story. This is the belief system. This is what happened. This is how it felt.” I think that's really important, too. She wasn't precious; she was saying, "I need you to know this stuff. I'm sitting with it. I'm wrestling with it." You could feel her pain in her work.

I don't trust people who are alive and paying attention and don't feel pain about what's happening. As a writer, she earns my trust right away because I can tell that she knows we are all going to die and she’s terrified, just like I am.

AG: You quote Butler, saying that, “Our fatal human flaw is the combination of hierarchy and intelligence.” Do you think it is human nature to create hierarchical systems of difference, and if so, can we change this?

AMB: Based on our behavior, this does seem to be our nature. For as long as we can look back, we see forms of human hierarchy. There's some leader, there's some chief. But not all these power systems need to be fatal. I think that one reason for hierarchy is that it's actually much harder to facilitate direct democracy, direct communication, and relationship building. And now we’re so caught up in the capitalist expectation that everything must constantly be scaling up. It's very hard to keep the relationships that you need intact once you get to a certain scale. I think that we default to hierarchy instead of deepening the kind of relationship work it would take to create other, less centralized structures. But, I'm not a purist in this belief. There are some productive hierarchies. For example, I believe in hierarchies of age. My mentor, Grace Lee Boggs, passed away when she was 100 years. When I met her she was 92. When I encounter someone who has lived for three times as long as I have, and we’re having a conversation, I want to weigh their words appropriately. That kind of intellectual hierarchy works for me. If you're actually my teacher, let me defer and submit to that.

Unearned hierarchy is where it becomes really harmful. White supremacy, for example. That's an illusion that only causes tremendous harm. I try to disrupt unearned hierarchies whenever I can, even if it’s a simple conversation with a white man who is expressing supremacy in which I maneuver the situation to force him to understand me differently.

“(…)we must figure out the intention that we’re moving towards. What must we do to survive? Some people articulate it as a goal or a vision. But how do we also make sure, as we’re changing, that we are actually good at it and that we’re not just changing in a reactive way(…)”

AG: What is “intentional adaptation”?

AMB: I really thought about this when I was writing the book, because adaptation is, of course, an innate instinct. When birds overcome environmental and geological challenges to fly south for the winter, they know they must do that in order to survive.

But for humans, we must figure out the intention that we're moving towards. What must we do to survive? Some people articulate it as a goal or a vision. But how do we also make sure, as we're changing, that we are actually good at it and that we're not just changing in a reactive way, which is what I think often happens in our current political condition. Me hearing something and getting mad and posting about it on social media is a reaction, not an adaptation.

AG: You write extensively about your favorite non-human organisms that demonstrate collaboration and resilience. What are these, and how did you choose them?

AMB: I love non-humans so much. I've got four of them tattooed. So maybe I'll talk about those, because those really are four of my favorites.

I love cows. They are so gentle and familial. I never knew that cows actually frolic and run around. They play. Some work that I do occurs in a dojo that's up in rural Petaluma, California. It's an old barn that's been transitioned into this dojo, and there's a huge glass window on one end of it through which you can see cows out in their field. We'll be inside weeping, crying, moving some trauma through, and six cows will be over there just watching us patiently, lovingly. I have fallen in love with cows.

Elephants are also familial. They're massive and mighty and they could do so much harm, yet they're often so gentle. They take care of each other.

I really wanted to have the cow and the elephant on my arm, because I've had a lot of insecurity around my arms. They have stretch marks, and they're big, and they’re a part of me that I've never really been able to change. So, I loved having these unapologetically big creatures on my arms. It's part of my healing process.

Then, I have a little turtle. I love the message of the turtle, which is that you have everything you need in terms of a home right there with you. Turtles also remind me to slow down.

My final tattoo is an octopus. The octopus feels like my facilitator self. I have all these different hands, all these different tentacles, so when I'm holding a space, I can really feel what’s happening in all parts of it. “Oh, it’s heating up over there; someone's crying over here; there's a lot of love and laughter happening over there; lunch is running late here.” How many things can I keep in my mind at one time? I also love octopuses because they can escape from anything. They do it by relinquishing form. I think about that for us, often. It's why I pull away from the institutionalization of things and from the idea that structures have to stay a certain way. In order to get out of capitalism, we're going to have to move like an octopus; it's going to be a small exit.

Anyway, those are some of my favorites, as well as nymphs, butterflies, dragonflies, and then caterpillars–transformational creatures. I also love the humility of the caterpillar.

AG: You describe conflicts of imagination as being among the biggest problems of contemporary society. What is the difference between “battles of the imagination” versus “imagination and collaboration,” and how might we move from the former to the latter?

AMB: I learned the terminology of imagination battle from my friend Terry Marshall, who works with the group Intelligent Mischief. Imagination battles begin with a subjective idea that is positioned as the truth and forced onto others. I think most of the inequalities that we face are exactly that. For example, the idea that men are superior. That's purely imaginary. That has nothing to do with reality at all. But once an idea is brought into the world, reality can be structured around it. Ideas can become systems of oppression. We know that because, to this day, we are still fighting for basic shit. Like equal pay, right? It's ridiculous. That’s an imagination battle—when you have to fight against something that is being imagined about you or against someone who is doing that imagining. Maybe you are imagined to be dangerous, or inferior, or less worthy of the miracle of life. We have to fight these ideas.

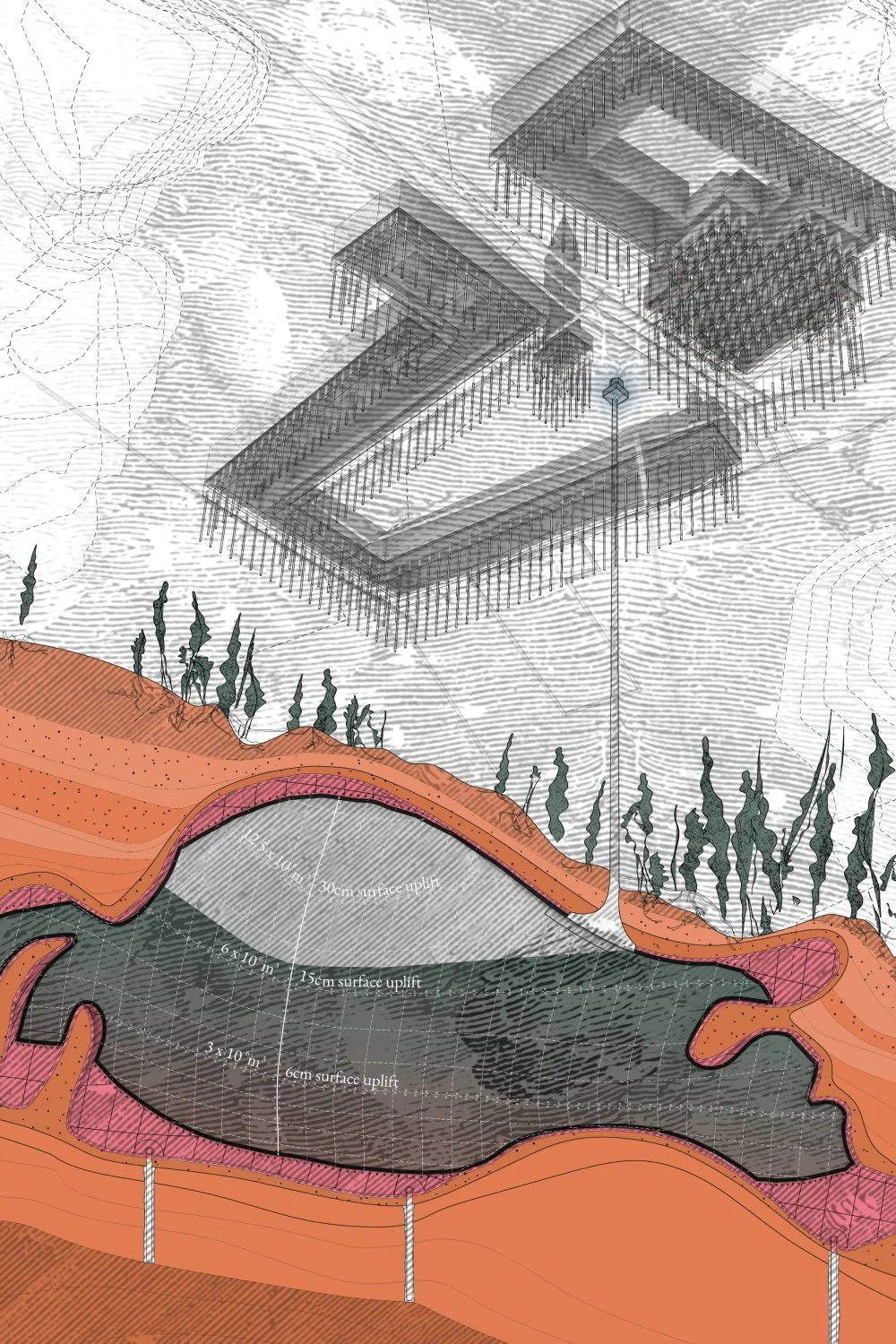

Imagination collaboration is inviting someone to be part of an idea or to create an idea with you. I did this recently. There's a woman who I adore, and I wanted her to be part of my work. I said to her, "I really want you to be a part of the work that I'm doing. I'm not going to move too far forward with imagining what that looks like because I want us to co-imagine it." Part of why I want to work with her is because her imagination is very different from mine. She's a builder. I'm more of a dreamer. I’ll imagine a house floating in the sky with waterfalls pouring off the edges. I could think that up, but she'd be like, "Right, so we need hover boards to lift it up, and we need a light, aerodynamic structure that could actually move, and then we need some way to catch and recycle the water." She's that next level. Her imagination is systematic and structural. When Deem talks about “Designing for Dignity,” I think about how much of imagination collaboration is about dignity and harm reduction. How do we make sure that the people who are most impacted by whatever's happening in a place get to co-imagine how that place can be? How do we prevent those people from being excluded from the conversation because of someone else's power dynamic imagining? Here in Detroit, we've been through this massive gentrification push. But who's talking to the homeless about their ideas for how the city could work better? They’re the ones seeking shelter every winter. I bet they have brilliant ideas about how to meet the needs of divergent populations within a city. This is a big part of disability justice; if you don't have people who use wheelchairs or people who are blind or people who are deaf at the imagination table when you're creating a building or an event, then you will find out later that whatever you made is not actually accessible to the people it was intended to be for.

If you have privilege in an area, it's very hard to see what is lacking in that area. I get caught in this all the time. You have to cultivate relationships with people who can see more than you and who can see differently than you, so that together your co-imagination becomes something that actually works for everyone.

AG: You write that there's a conversation in every room that only the people present can have and it's our responsibility to find that conversation. Tell us more about this idea. What tips do you have for finding those conversations?

AMB: I love that this is true, and as a facilitator, it's really a Golden Rule. When people are super frustrated and feel like nothing is going anywhere, it's probably because you're missing the conversation that you need to be having. As far as finding it, that really depends on the size of the group.

If it's a small group and you have a few hours for a conversation, just ask. What would be most useful for us to spend this time on? People always have ideas. Simply asking what is most pressing to talk about can really help. Asking, “What is the next, most elegant step we can take?” is a great question, because sometimes folks get overwhelmed by the scale of the problems that we're facing. How do we find the conversations that help us see our impact?

One of my favorite tools for a larger group is this Post-It synthesis process. Everyone writes the conversation they want to have on a Post-It and sticks it on a wall. Right away, similar conversations become one column. Then different conversations each become a new column.

We pair people up and ask them to discuss what the group should talk about for the next four days. What is crucial? Then they team up with another duo and compare notes. Between everyone involved, what are two conversations that would be super satisfying and nourishing to have as a community? This process sharpens as you add more people to it. By the end, you've got five, or maybe ten, conversations. When people get to talk about what they actually want to talk about, it’s mind blowing. Suddenly they get creative, generative, brilliant ...together.

“You have to cultivate relationships with people who can see more than you and who can see differently than you, so that together your co-imagination becomes something that actually works for everyone.”

AG: You make an important point that productivity and success, especially in the U.S., are often requisites for human rights: for food, for housing, and for care. How do you envision your own value outside of a system of capital?

AMB: I'm constantly trying to figure this out. When I did my sabbatical in 2010, this is one of the major lessons that emerged for me: recognizing that I have a worth that's not just what I can produce for other people and it's because I was born a miraculous being and just being alive and being kind are enough. Instead of thinking that I need to be a star, write a book, or make a movie, can I just be kind? Seeing the benefit added to other people’s lives when they receive kindness, feeling in my own life the number of times I have been saved by some strangers' kindness, some mercy—that has been really helpful for me.

I have, multiple times in my life, turned away from success because it didn't align with my values. For Emergent Strategy, I didn't promote it, I didn't push it, I didn't think of it in terms of sell, sell, sell. Actually, I did the opposite. I told people to take pictures of the pages that interested them or to borrow a copy from someone else. That's the essence of the book. The rest is just an extended metaphor. But Emergent Strategy has sold. A lot of people have purchased it. It's the highest selling book that my publisher has ever put out, and Pleasure Activism is close behind that. The lesson has been to keep putting my attention on how to be a channel of something larger than myself. That’s been my source of hope. How does the universe want me to make things better? How can I be a tool of something that's divine? It's kind of ridiculous to say it in polite company, but it is what I believe I'm up to and why I believe I'm successful. I believe that there is a rightness in the universe and that I am helping us align with it.

AG: You write that we are best when we are acting out of love. Why do you think this? How can we infuse our work with love? How do we incentivize others to do so, too?

AMB: Love is such a good version of humans. That's when we are generous. That’s when we offer something without needing to receive anything back. It’s what makes us attentive. When you love someone, you pay so much attention, including paying attention to whether they might not have something that they need. The best is when I'm in a love that expands beyond the one to one, when I'm in a circle of friends who realize we love each other. I have several groups that are my inner circles. I've known them for a long time; I trust them very deeply; I love them very deeply. We hold each other up with generosity.

Right now, two very important individuals in my life are going through massive personal crises. There's no hesitation in my system about wanting to catch and hold these sisters of mine that I love so much. A lot of what I mean by love is connected to mothering. Think about the way a mother looks at her child like, “you're perfect.” I work as a doula so I see that look.

I definitely think movement work should be a space where love gets fomented. I think we should be working to love each other and to create spaces where people feel loved and sustained. Unfortunately, movement work is often driven by fear and scarcity. People are coming together just because they're all terrified of the same thing or they're coming together because there's a deep, urgent scarcity. These conditions create burn out. There’s a place in Emergent Strategy where I talk about “moving at the speed of trust,” and I think “moving at the speed of love” is often what I actually mean.

AG: You quote Toni Cade Bambara about the role of the artist, saying that the artist must make the revolution irresistible. How do you make your ideas irresistible?

AMB: I really try only to share ideas that are irresistible to me. When I find an irresistible idea, I share it often. I'm not afraid of pleasure, so I try to create spaces in which people feel really good. I think that, for most people, getting to be their authentic self, and be welcomed as that, is an irresistible experience. I try to create that as much as I can. I want people to have a good time. I feel it's politically important to be a black woman having a good time.

I let people know that all the time. I'm like, "They tried to kill us; they tried to steal our joy; they did not succeed. Look how happy I am." I'm happy yet I'm still connected to the great suffering of my time. But despite everything, despite the work, despite all the shit that’s going on, I’m still finding joy each day. I’ve received a lot of feedback from people who told me that they needed someone to tell them it was okay to experience some joy each day. I believe it’s a measure of my freedom to be able to experience the joy that's available to me in this moment of my life.

I love your questions.

AG: Thank you, and these are questions that our editorial team came up with together. It's myself, Isabel, and Larenz. They're wonderful.

Fractals are a big part of Emergent Strategy: the idea that small actions replicated on a large scale create massive and complex systems. How do you personally transform yourself to transform the world?

AMB: I'm a big practice person. I am constantly practicing things. I have several key practices that I use for self-transformation work. One is the practice of 1000% honesty, which is very, very scary and daunting for most of us. We're trained and socialized to be polite even—and sometimes especially—if it means being dishonest. If you think about it, you’ll start to notice. How many lies did I tell today? How many times did I keep the truth just tucked right in my throat? It could have just come out, and it might have made the situation better. It might have saved resentment from building up. It might have helped us get to the project we actually need to be working on. Try just that one thing. Commit for the next three months to being 1000% honest in even just one or two of your relationships. I would bet that most people would find that their life fully transformed in that time.

Another crucial practice is asking for help. I have to unhook this from my perfectionist Virgo self. This could mean asking for feedback or admitting that you can’t do something on your own. I will often assume that someone doesn't have any feedback for me because they didn't volunteer it. Even when I get a lot of affirmation from my readers, I'm still thinking, “Okay, but I also want to know your critical opinion. What kinds of shifts come next?” Asking for the help you need will make you more able to perceive and offer others the help they need.

AG: What is “design” to you?

AMB: Design is how I make something both beautiful and functional. I think of myself as a secret designer. I'm always designing spaces. In my head, I’m designing a bath house with a dispensary attached to it. I know every aspect of how it looks and feels.

AG: Yes! Can I live there?

AMB: Yes, we are all going to live there. We're going to have apartments. I love coming up with these ideas by myself but I also want to grow into designing with other people. It’s easy for me to think I am perfecting something on my own. But, as I explained before, the more people are involved in the design process, the more people the design will work for.

AG: You are a designer. That was the first thing I thought. I haven’t seen you identify as a designer but you’re definitely giving us a framework. Do you think Emergent Strategy is about design?

AMB: I do, and I'm understanding it more and more. I think if someone had asked me that when I was creating it, I wouldn't have understood it that way. So much has happened around my understanding of complex thinking and complex design. There are so many people who are practicing variations of this and have been for a very long time.

One of the important things about Emergent Strategy is that I didn't craft it out of thin air. I saw these processes happening around me. The parts about resilience and transformation are really about asking how we can design ways of being together that make it impossible for us to cause so much harm to each other. It's not just about being more forgiving. We have to design structures; we have to design relationships; we have to design justice.

That's where design gets really exciting and interesting to me. In Detroit, we recently acquired this new building for Allied Media. It’s been a struggle because there are some people already in that space and the pace at which they want to move out doesn’t align with the pace at which AMP and our partners need to move in. This has actually been quite devastating.

It's also meant we have to get our hands in the dirt of being designers and developers in our city. It's much easier to sit outside of that and be like, "Fuck developers, they're all gentrifiers." But, if we actually want to make a play for this city as a space that we still get to be in, what does place-based revolution work look like? We have to acquire land; we have to acquire property. We had a session with the building where we asked, "What would you want to do to design this neighborhood?" It was funny because there were people at the session who were community organizers and people who weren't. All the organizers were like, "We could never know that. We need to go talk to all the people here and figure that out with them." And then the folks who weren't organizers were like, "Well, we should have a coffee shop and we should definitely do this, this, and this too."

While there was no lack of good intention, you see how quickly people will put their design over another person’s experience. We are trying to pull away from that and push towards a more socially responsible design. Furthermore, how can design be not just socially but environmentally responsible? How can we make sure our design has the right relationship to people who were here before us? How can we make sure our design has the right relationship to the planet? How do we serve folks who actually have a relationship to this place, instead of more same-ification. I don't want people to ever be like, "I just landed in Detroit and it’s exactly like San Francisco.” I want it to feel distinct. New Orleans is like that—I feel protective over the distinct quality of that place. That quality requires a whole system of thinking and care.

AG: Tell us about your latest book, Pleasure Activism. How do the methods in Emergent Strategy work with the ideas outlined in Pleasure Activism?

AMB: I was surprised that Pleasure Activism ended up being my next book, and I’m also surprised that it's going so well. The main idea is that what you pay attention to grows. It’s the explicitly overlapping principle that if we put our attention on pleasure—on joy, satisfaction, and happiness—we can develop these things.

Audre Lorde’s 1978 text Uses of the Erotic is the guide for Pleasure Activism. She talks about how we have been convinced that we don't deserve to feel joy, to feel pleasure, or to feel the erotic aliveness of ourselves and that this repression is intentional. As long as we don't think that we deserve these feelings, we will settle for self-negation, suffering, depression, and stagnation. After reading that over and over again, I was thinking about how I might put my attention, as a black woman, on my own dignity. How might I put my attention, as a black woman, on my freedom? How might I put my attention, as a black woman, on feeling good? I deserve to feel good. My hurdles have been convincing myself that I deserve to feel good as a black woman, as a fat woman, as a queer woman, as an organizer woman, and just as a woman.

Many communities are awakening to these ideas now. When it feels good, more people want to be part of it. We have numbers that say that we need to be fomenting an irresistible space that everyone wants to move towards. It should feel like home; it should feel delicious; it should feel caring. It should feel like a community. That's also a design piece. Several of the groups that I’ve been working with are now co-creating their own spaces, which is very exciting to me. Imagine what our movement looks like in ten years if we focus on making it an irresistible and compelling space rather than a mine field, which is what my political work often felt like. I do also want to say that rigor has a big role in pleasure. There's eroticism in having a high standard, in withholding, and in not pretending.

AG: What do you want to do next?

AMB: I'm going on a sabbatical. But first, I'm actually working on another book. My next book is about facilitation and mediation. The goal is that I'll complete the draft to turn in before I go on sabbatical in December. That will mean that I have completed four books in the time since my last sabbatical, and that feels huge and good. That's also not counting fiction. I've finished two novels in that time, too, but those are just my private stories right now. I feel like I’ve put a lot out there. I've toured books. I've put on a ton of events. I've facilitated a lot of sticky movement moments. I need time to sit and integrate all that has shifted, moved through, and changed. I need time to not hear my own voice. I need time to get quiet and listen to what's next.

Emergent Strategy has a lot to do with decentralization, but when you start to be recognized for your work there's an automatic centralization that happens. Some of that is fun. I can see how it can be used to move the work. But it's also really important to me that readers understand that emergent strategy is being done by many people. If I'm not replaceable, then I haven't done my job well. If other people can't come in and do the work, then I haven't learned how to teach, to offer, and to hand myself over.

My plan is to pack a suitcase full of books with one swimsuit, one sarong, and a hat, and then go someplace where it works for me to be reading all day in a bikini. I’ll come home when I’ve read everything in the suitcase.

AG: Thank you so much for this moment.

AMB: Thank you.